Will Debt Limit controversy destroy faith in the US public credit that Alexander Hamilton established?

Brinkmanship over the debt limit has become a political ritual where threatening default could erode long term confidence in US public credit

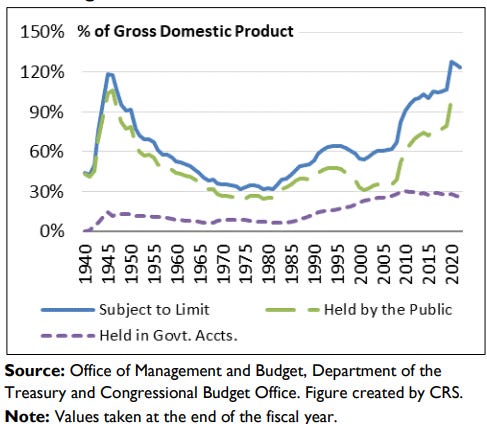

The row between the Republicans in the House of Representatives and the Democrats in the Senate and President Biden’s Democrat administration is a replay of previous partisan games between Congress and the administration. The Congressional Research Service report on the Debt Limit explains that ‘debt limit places a statutory constraint on the amount of money that Treasury may borrow to fund federal operations. Federal debt reached its current limit of $31.38 trillion in January 2023’. About 98 per cent of all Federal Government debt is covered by the debt limit. This statutory limit provides Congress with a powerful tool that offers plenty of opportunity for institutional conflict. How effective it is as an instrument of fiscal control is open to doubt.

Federal Debt Subject to Limit as a Percentage of GDP, FY1940-FY2022

Source CRS

No way to run a railroad – the debt limit is a clumsy tool

Both parties have played chicken with the US public finances to score partisan points, running the risk that at some stage the US Treasury would not be able to pay the Federal Government’s bills. While the debt ceiling is a powerful political tool it is not clear how useful an instrument it is in terms of framing choices around spending, taxing and borrowing. The General Accountability Office in its study Debt Limit Delays Debt Management Challenges and Increases in Uncertainty in the Treasury Market published in 2011 concluded that ‘the debt limit does not control or limit the ability of the federal government to run deficits or incur obligations. Rather, it is a limit on the ability to pay obligations already incurred. While debates surrounding the debt limit may raise awareness about the federal government's current debt trajectory and may also provide Congress with an opportunity to debate the fiscal policy decisions driving that trajectory, the ability to have an immediate effect on debt levels is limited’. In the process the Federal Government has been closed several times and there has been scope for a default on US Treasury debt. As Ben Bernanke the former Federal Reserve Chair has told Congress it is no way to run a railroad.

The problem with using the debt limit as the main instrument in framing fiscal policy is that in the process of the political row the US Federal Government could run out of money before there is a settlement. Since the debt ceiling reached its limit in January the Treasury has taken ‘extraordinary measures’ to conserve and manage cash until the matter is resolved. It has now reached the position where the scope to manage existing cash, holdings in various accounts and periodic tax receipts will not ensure there is the money available to pay federal employees, recipients of social security (old age state pensions) payments and make payments on servicing US Treasury debt. These are no abstract economic concepts in an academic mathematical model, but real cash payments that must be made. The greater part of interest rates fall due in the middle of a month. The scope to use these extraordinary measures of cash management is about to run out of road.

The Congressional Budget Office in a paper just published, Federal Debt and the Statutory Limit May 2023, projects that if the debt limit remains unchanged, there is a significant risk that at some point in the first two weeks of June, the government will no longer be able to pay all of its obligations. The extent to which the Treasury will be able to fund the government’s ongoing operations will remain uncertain throughout May, even if the Treasury ultimately runs out of funds in early June. That uncertainty exists because the timing and amount of revenue collections and outlays over the intervening weeks could differ from CBO’s projections. It is worth exploring the budget arithmetic that the US Treasury is having to manage in order to understand the issues involved, and they are well presented by the CBO research note.

On April 30, 2023, The US Treasury had $316 billion in cash. Through further special measures the CBO estimates it may have an additional $41 billion of cash. The CBO set out those extraordinary measures. They include:

• ‘Continue to suspend the investments of the Thrift Savings Plan’s G Fund.5 Otherwise rolled over or reinvested daily, those investments totalled $24 billion as of April 30, 2023.

• Suspend the investments of the Exchange Stabilization Fund.6 Otherwise rolled over daily, such investments totalled $17 billion as of April 30, 2023.

• Continue to suspend the issuance of new securities for the Civil Service Retirement and Disability Fund (CSRDF) and the Postal Service Retiree Health Benefits Fund (PSRHBF), which total about $4 billion each month.

Postpone reinvestment of securities held by the CSRDF and the PSRHBF and suspend interest payments to those funds. On June 30, 2023, $133 billion of securities held by the CSRDF and the PSRHBF will mature, and an additional $12 billion in interest payments are scheduled to be paid, making roughly $145 billion’.

The payments that need to be made over the next five or six weeks include on the CBO estimates are :

• ‘A large share of the pay or benefits for active-duty members of the military, civil service and military retirees, veterans, and recipients of Supplementary Security Income (about $25 billion) is disbursed on the first day of the month.

• Interest payments are made around the 15th day and on the last day of each month. Mid-month outlays are typically only $3 billion, but once per quarter, payments of interest on 10-year notes and on bonds (which will next be paid in May) increase mid month outlays to roughly $50 billion. End-of-month payments have ranged from $10 billion to $16 billion over the past six months’.

US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen’s problem: about Half a Trillion dollars out of pocket

The CBO projects in its paper that the US Treasury ‘probably needs resources totalling between $1.9 trillion and $2.2 trillion to finance ongoing operations for all of fiscal year 2023. $1.1 trillion in resources (a combination of increased debt, extraordinary measures, and cash drawn down) have been used’. CBO estimates that cash and extraordinary measures available for the rest of the fiscal year will total $0.5 trillion, about two-thirds of which is currently available leaving between $0.3 and $0.6 trillion. None of these numbers can be precise; neither the Treasury, the Office of Management and Budget nor the Open Market Desk of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York could with the best will in the world guarantee reliable precise numbers. That is why the Treasury needs the flexibility of borrowing to manage the Federal Government's fiscal needs. A clumsy fiscal rule should have no place in the scheme of things and certainly not a rule as crude as the present debt limit.

Radical Conservative insouciance about dangers and consequences of brinkmanship and default

The politicians and the public that elects them have become used to this brinkmanship and often approach it with insouciance. When nothing disastrous happens the next time the game is played, they are emboldened to be more reckless and intransigent. In evidence to the Joint Economic Committee of Congress in 2013 for its report The Economic Costs of Debt-Ceiling Brinksmanship that looked at the debt ceiling crisis in the summer of 2011, Mr David Malpass, a veteran Republican economic idealogue, offered a clear statement of the political reflex that is being increasingly deployed. Mr Malpass suggested that in ‘contrast with August 2011, it’s unlikely that a major credit rating agency would downgrade the U.S. credit rating. I think financial markets would greet a partial shutdown of government spending during the debt limit negotiations with a yawn or quiet applause’.

Mr Malpass’s evidence to Congress offers the locus classicus of fiscal irresponsibility

Mr Malpass went on to suggest the ‘Administration would like to use financial markets to scare Congress into a clean debt limit, but I think the reality is that voter reaction will be the stronger referee on the debt limit negotiation. If voters think the negotiations are reasonable and constructive, they’ll tolerate a partial shutdown, as will financial markets. There’s no indication that financial markets are worried about a default or technical default on U.S. debt’.

The Treasury Department normally tries to cajole Congress by warning about the time - X-date - will arrive. The day when the Federal Government will run out of cash to pay its bills in an orderly way and when the US Treasury could default on its debt. Estimating how swiftly the Treasury would run out of cash is difficult. There is normally a debate about how long the Treasury can keep spending going and if in the end there is a technical default what impact it will have on financial markets.

There is always money in the federal government to pay the bills?

The federal government holds cash in about many different trust funds. About twelve big funds account for over 90 per cent of its cash holdings. The amount of cash held and spent is erratic, however, depending on irregular flows of receipts and settlement of bills. Giving priority to debt payments over other federal spending commitments to avoid a default is technically feasible because they are made over the Fedwire, a computer system separate from the one that handles other payments. While it may be prudent to do so to maintain the ‘full faith and credit of the United States’ and technically possible to do. it is not certain that it would be financially feasible.

Mr Donald Marron, Director of Economics at Urban Institute, in evidence to the same JEC inquiry on events in 2011 pointed out that ‘Interest payments average only 8 percent of federal revenues at the moment, but cash management isn't about averages. Interest payments are lumpy, and tax receipts are lumpy and uncertain, so the Treasury would have to take care in matching them. In addition, there's a risk that a debt limit crisis may cause problems rolling over maturing debt issues. For both reasons, debt prioritisation is harder than sometimes claimed, and Treasury might unintentionally find itself short of cash when an interest payment comes due or maturing debt needs to be rolled over’.

There would be a cost to the US as a borrower if it should ever default. In 1979, for example, the Treasury accidentally did default on a small portion of its debt for highly technical reasons. The default was narrow, applying only to T -bills owned by individual investors, and was rectified in a few weeks, but the market reacted badly, T-bill interest rates increased by about 60 basis points after the first default and remained elevated several months thereafter. The default thus significantly boosted the government's borrowing costs.

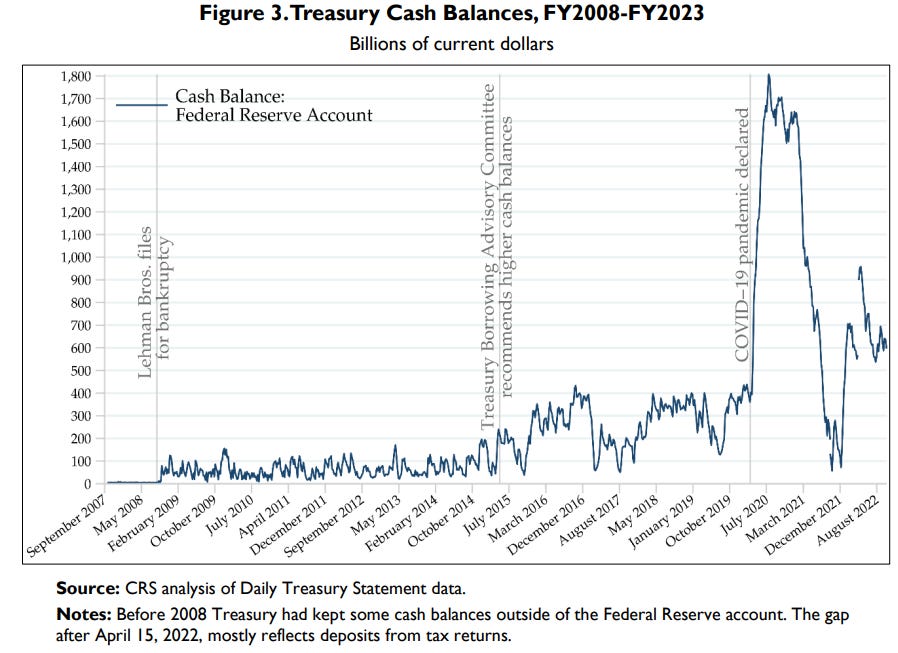

Both public bodies and private organisations offer assessments of the amount of cash the US Treasury has in hand and when it will run out, when there are political disputes about the Debt Limit. In 2015 Lou Crandall at Wrightson ICAP produced a chart illustrating the glide path to Carey Street ( traditional location of the bankruptcy court in London) and the Congressional Research Service has looked at how the Treasury cash balance has varied over the last fifteen years.

In 2011 US federal debt default was too close for comfort

There is a lot of concern about how markets would react to a US Treasury default. In 2011 it was a close-run thing. In the process the US lost its AAA credit rating from Standard and Poor’s. As it happens yields on Treasury debt fell. David Malpass drew this to the attention of the JEC inquiry pointing out that the ‘10-year Treasury yield fell from 3.2per cent to 2 per cnet in July and August 2011’. This fall in Treasury bond yields should be interpreted with caution. Part of the increase in Treasury bond prices was driven by a a ‘flight to quality’. In a time of crisis, albeit a US fiscal crisis, while US Treasury bonds retained status as the world’s ultimate ‘risk free’ debt security, investors in the first instance still turn to Treasury debt. Dr Mark Zandi of Moody’s Analytics, for example in evidence to the same JEC inquiry in 2013 said as ‘Just a point of clarification, a very important one. The Treasury yields fell. Every other yield rose. So borrowing costs to businesses, borrowing costs to consumers, to households because of higher mortgage rates because of the spreads widened because of the concern’.

There was no default in 2011 but the brinkmanship had an economic cost

The debt ceiling crisis in the summer of 2011 had a cost in two senses. The first was a direct cost to the federal government in narrow debt management terms. The second was that the controversy was only settled when the Administration agreed to legislation that delivered a discretionary tightening in fiscal policy.

When the Government Accountability Office (2012), looked at the 2011 crisis’s impact on US funding costs it noted that in public expenditure terms it was an expensive episode. The federal government lost money by being unable to invest in its normal pension funds to cover the costs of future employee pensions. There was less efficient management of debt due to the need to preserve cash and the advantage that the federal government enjoys has in relation to private businesses narrowed during that debate, suggesting that investors saw greater risk in holding Treasuries. Overall GAO estimated that the federal government spent an extra $1.3 billion in interest during fiscal 2011 as a direct result of the debt ceiling turmoil. The Bipartisan Policy Center estimated that over the fall maturity of the debt involved the full figure would be $18.9 billion.

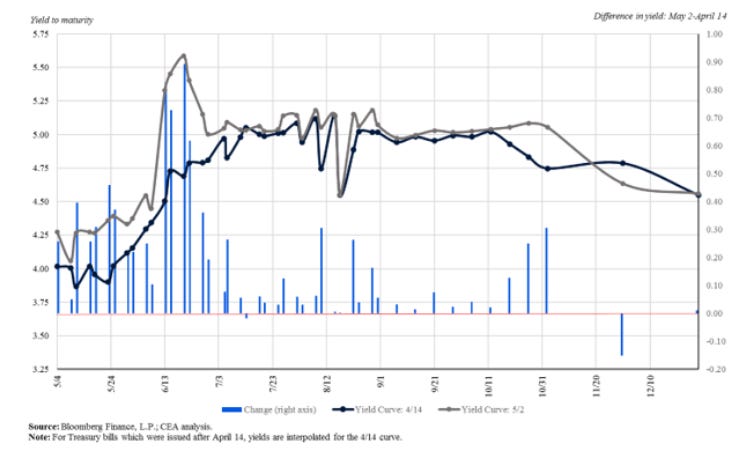

The chart below shows how different political spats over the debt limit have contributed to a measured increase in the costs of managing US Government Debt. Treasury bill prices display an identifiable pickup over the relevant period of politically driven contention.

The Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA) that resulted out of the contentious negotiations over Debt Limit that year, framed the way Congress approached the debt limit in the next decade. The BCA resurrected; previous budget enforcement mechanisms directed at reducing federal deficits. The Republican Speaker John Boehner insisted that increases in the debt limit under the Act had to be matched by spending reductions over that decade. In looking at the effects of the BAC Act in 2013 Mark Zandi pointed out ‘you add up the effect of the spending cuts and the tax increases, it’s about 1.5 percentage points of GDP, that’s the most fiscal drag this economy has had to digest since just after World War II during the War drawdowns’. At a time when very loose monetary conditions, led by unorthodox innovations such as QE and forward guidance, could not get policy traction in terms of stimulating the economy, fiscal policy was unhelpfully tightened. The hesitant use of fiscal policy after the immediate efforts to stabilise output between 2008 and 2009, with hindsight appear to have been a mistake contributing to slower growth in the recovery period after the great recession and as a contribution to the secular stagnation and form of stationary state that advanced economies exhibited in between 2010 and 2020 before the public health covid shock.

Rising costs of borrowing and rising costs of insuring US Treasury Debt against default

In the present crisis the Biden Administration has catalogued a similar pattern of rising interest rates on government bills. The White House has noted using Bloomberg data that yields ‘on Treasury bills with maturity dates around the X-date have increased considerably — directly increasing the cost of borrowing for the government and thus the cost to taxpayers. The figure below demonstrates this; since the middle of April, yields on short-duration Treasury bills around the expected X-date have increased by nearly 1 percentage point, or roughly 20 percent.’

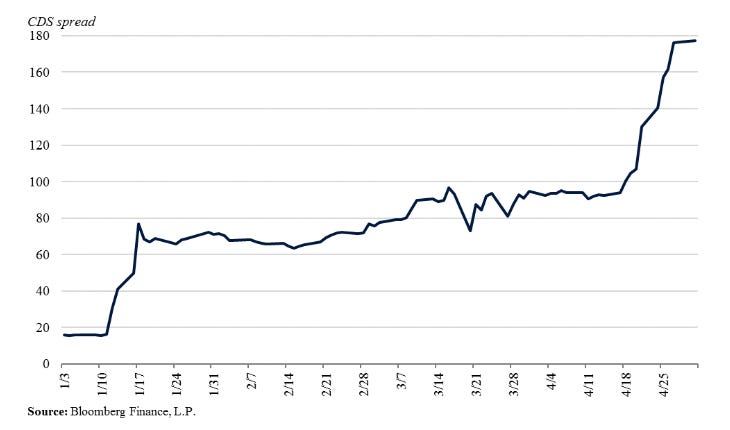

The White House has also noted that the ‘cost of insuring U.S. debt has also risen substantially and is now at an all-time high, reflecting increased worries about a U.S. default. In fact, credit default swap (CDS) spreads—the insurance premiums that must be paid to insure U.S. debt—started to increase dramatically in April’. In many respects the credit default swap rate is a better guide to market confidence in US Treasury securities because it is not distorted by issues of market liquidity and other technical trading distortions that probably have increased in recent years, not least because of a less liquid repo market.

One Year US Government Bond Insurance Premiums

Defective American Political culture that could not deal with the Lehman and the banking crisis

Fiscal rules laid down in law that require primary legislation if they are to be changed do not have a role in a properly managed modern economy. It is not clear how useful non-legally binding fiscal rules are. Yet brittle rules set in law that cannot easily be changed can cause huge expensive and unnecessary damage. The reason why Lehman Bros could not be rescued in 2008 was that it was bankrupt. Indeed, it was more bankrupt – according to the Examiner in Bankruptcy – than presented by its misleading balance seen by the Federal Reserve. Neither the Federal Reserve nor the US Treasury had a mandate in law to save a bankrupt bank without primary legislation being passed by Congress. When the Administration tried to get the legal powers to equip the Federal Government with the powers to manage the growing financial crisis Congress initially refused to pass the legislation. This further aggravated and exceptionally difficult position. The heart of the problem in 2008 was a defective American political culture that could not modify its laws swiftly to manage a crisis. That political culture was failing before the Obama Administration and the emergence of the Republican Tea Party Congressional caucus. Since 2008 in terms of the American political culture things have moved on with a dynamism that few people would have expected fifteen years ago. The result is that an overly legalistically framed Federal fiscal policy that was a genuine nuisance in terms of efficient economic management has become overlayed by a toxic and polarised political culture that makes making legal and legislative progress even in crisis circumstances a lot more difficult.

Will Alexander Hamilton’s great achievement be demolished as a result of a polarised and toxic modern political culture?

After the ratification of the US Constitution Alexander Hamilton was appointed the first US Treasury Secretary and his first duty was to prepare a report on public credit that was transmitted to Congress in 1790. Its key observation was that countries that pay their debts in a reliable way enjoy as strong public credit in the way that private individuals do. Following the revolutionary war of independence the thirteen colonies had been best with financial problems, partly problems arising out of the costs of financing that struggle for independence from Great Britain. All the colonies had incurred substantial debt. Some states such as Virginia that were prudentially run, had paid them off. Others such as Massachusetts had incurred more debt. Hamilton’s controversial proposition in his Report on Public Credit was that the Federal Government should take responsibility for all that debt and pay it down and in doing so would establish the full faith and credit of the United States.

Hamilton had learned the lessons of Dutch and English funded public debt in the 17th and 18th century. In its wars for independence and religious freedom from Catholic Spain and against Catholic France, the Netherlands had been able to mobilise huge financial resources to pay for war material on a scale the Kings of Spain and France struggled to match. This was because the Netherlands could borrow cheaply. The reason was its confederation of communities could reach an agreement to collect taxes to repay those debts in an orderly and reliable way.

Following the Glorious Revolution in 1688, that established the modern English parliamentary protestant monarchy, William of Orange the Dutch Stadtholder became King of England. William III wanted to ensure that England fully participated in the Dutch war against King Louis XIV. This required money. Until then then England, excepted for a short period during the Commonwealth Protectorate (the Republic presided over by Oliver Cromwell as Lord Protector between 1649 and 1659) had played little role in 17th European geopolitical events because the Stuart Kings could not obtain the cash they needed from their parliaments to finance any European ambitions they may have had.

All this changed in the 1690s. Following the Glorious Revolution William III remodelled English government finance on the Dutch example. Parliament voted taxes to fund the repayment of debts issued by the new protestant royal government. The Bank of England was set up by act of parliament in 1694 to manage this debt. The result of what historians have called the English Financial Revolution was a huge capacity to borrow cheaply in its domestic currency and an ability to mobilise huge amounts of borrowed money in relation to its national income. In the long 18th century of wars with France, Great Britain was able to finance war much more easily than France. The French economy was for most of the time until the start of the Industrial Revolution at the end of the 18th century bigger and as, if not more, commercially buoyant. It could not raise money on financial markets in the way that Britain could.

The Ancient regime had a toxic political culture where despite apparent royal absolutism the Kings of France could not raise the taxes necessary to service the war and other debts they incurred. Worse their principal sources of revenue on agriculture had a high deadweight cost that progressively eroded that tax base. This was catalogued by Francois Quesnay his pioneering manuscript Tableau économique published in 1758.

This was the lesson that Alexander Hamilton learnt from the Dutch and British experience that a funded public debt that is never defaulted on creates a public debt that lenders trust. That in turn gives great opportunities to a government that enjoys that credit to carry out its ambitions. The contemporary toxic political culture in the US may now be starting to test that public credit. When investors buy government debt they need to know three things. Has the government’s economy have the taxable capacity to repay the debt? Are there the political institutions in place to facilitate efficient revenue collection, such as income tax or a comprehensive goods and services tax. And does the borrowing country have a political culture with the willpower to levy the tax necessary to service its debts.

Can investors rely on American political culture to pay its debts?

In 2011 the US came close to the risk of a default. It would be wrong to exaggerate it, but it was a close risk. There was sufficient evidence of a political culture that does not cohere, to ask the question, could the US federal political system be relied on, to pay its debts in an orderly way, in all circumstances? The US has the economic resources and taxable capacity along with the revenue collection instruments such as income tax, but does it have the political culture now to do it? That latent question began to be explored. The downgrading of the US from AAA to AA by Stand and Poor’s was not an accident. When it happened the US Treasury Department was very angry and focused on an arithmetic error in the credit rating agency’s press notice. Instead the administration should have concentrated its collective mind on the question of how it maintains a political culture that appreciates the need to manage public debt with prudence and that gives legitimacy to putting payment of public debt first.

Since the summer of 2011 America and its political culture have travelled a long way. The big question is can America politically be relied on to service its debts in the future?

Warwick Lightfoot

12 May 2023

Warwick Lightfoot is an economist who was Special Adviser to the Chancellor of the Exchequer 1989 to 1992 and is author of America’s Exceptional Economic Problem.