What should financial markets make of a second Trump administration: return to President Ronald Reagan’s War Keynesianism?

Economic modelling of President Trump's tariffs as exercises in hyperbole, big geopolitical issue is rearmament led by US, financed by debt, with deregulation, cheap energy and big tech productivity

President Trump set out a clear economic agenda for his second administration. At its heart are increases in tariffs, income tax cuts and an ambitious programme of deregulation. The president has a long standing interest in trade protection and mercantilism. The use of tariffs is his preferred policy instrument for both economic management and revenue purposes. President Trump has speculated about using revenue from tariffs as a substitute for receipts from income tax. The principal economic indicators that guide him are bilateral trade deficits with individual economies and the performance of US equity markets.

National Republican Committee November 2024

This is a distinctive economic platform and violates the orthodox consensus of economists and international policy makers that has guided world trade and economic policy for over sixty years since President Kennedy launched the GATT round in 1962. It was launched when the US Congress passed the Trade Expansion Act. The GATT negotiations between 1964 and 1967 aimed to reduce tariffs by about a half. While the Reagan administration played eloquent lip service to free trade, with the Statement on Trade Policy in July 1981 , for example asserting that free trade was critical to ensuring a strong economy, the administration responded to shocks in traded goods industries with decisive protection.

A Great Truth of Classical Political Economy : Comparative Advantage

President Trump’s trade agenda disregards one of the great varieties of classical political economy. The principle of comparative advantage developed in David Ricardo’s book On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation in 1817. Ricardo’s great insight was to identify the opportunity for beneficial trade between two communities even when one economic community enjoyed absolute advantage in production of goods, provided there are differences in their absolute advantage offering them the benefits of specialising in what they were best at, they will benefit from trade.

Best to remember Joan Robinson’s advice: do not retaliate in kind

The benefits of free trade are so great that it is in the interests of economies to remain open to trade even when their potential economic partners erect barriers to trade.Unilateral free trade is in the economic interests of all economies. The Cambridge economist Joan Robinson famously expressed the matter in her article published in 1937 Beggar-My-Neighbour Remedies For Unemployment. ‘When other nations erect tariffs we must erect tariffs too, 'is countered by the argument that it would be just as sensible to drop rocks into our harbours because other nations have rocky coasts.This argument, once more, is unexceptionable on its own ground. The tariffs of foreign nations (except insofar as they can be modified by bargaining) are simply a fact of nature from the point of view of the home authorities, and the maximum of specialisation that is possible in face of them still yields the maximum of efficiency’.

President Trump’s trade policy will hinder other countries. Their response should be one of realism. The EU and UK should not, for example, occupy themselves, identifying items, such as Harley-Davidson motorcycles, Zippo lighters, Levi jeans and bourbon, to impose tariffs on to irritate the US as much as possible. It will be fruitless and only damage their own consumers.

They should avoid retaliatory tariffs and try to identify changes in their own policies that would not only help their own consumers and economic agents but satisfy American negotiators that they are taking US trade concerns seriously. The EU and the UK should end their long standing intransigence over American food and agricultural imports.

Derogating from open markets and imposing trade restraints results in losses of economic welfare but not to chaos

International trade that is frictionless unhindered by tariffs, quotas and less visible non price barriers to trade, can take full advantage of the international division of labour. This results in complex trade relationships and production and value chains. The more that international markets are open and trade is frictionless, the more optimal the international allocation of resources. Derogation from frictionless trade results in losses of economic welfare. It represents an opportunity cost. Yet derogation from optimal trade does not necessarily lead to chaos.

Economies, prices and exchange rates adjust

Much of the discussion of President Trump's trade policy, such as a general tariff of 10 to 20 percent and up to 60 per cent tariffs on goods from China, has assumed exaggerated consequences for both the world economy and for the US economy. This exaggerated discussion takes too little notice of the likelihood of adjustment in trade relationships between the US and economies such as China and the EU.

America’s trading partners have plenty of scope to reach agreement with the US on tariff reductions of their own that would hep their own consumers that go beyond agriculture

America’s trading partners will adjust and negotiate with the US on a bilateral basis. Much of the US focus will be on its various bilateral trade trade deficits with China, the EU and Germany. These trade deficits are central to President Trump’s mercantilist cast of mind. Exchange rates will also adjust. Tariffs are likely to be matched by offsetting falls in exchange rates against the dollar. An aggressive American trade policy that imposes tariffs could well elicit monetary policies directed at weakening exchange rates to make their traded goods sectors competitive.

As part of the bilateral responses to the Trump administration’s trade policy and new administrations wider geopolitical priorities, such as greater defence spending by European members of NATO. The EU will have scope to agree to a reduction in the EU-US bilateral trade deficit through higher imports of defence hardware and liquefied natural gas as part of its replacement of Russian gas.

Higher tariffs will tend to result in one off price increases rather than an inflation dynamic and will be offset by a stronger dollar

Higher tariffs and other impediments to trade will raise the costs of US consumers and place upward pressure on the American price level. It will, however, in character be a one off upward increase in prices rather than an inflationary dynamic, particularly if the Federal Reserve operates a broadly non-accommodating monetary policy.The combination of the tariff effects on exchange rates and a tighter domestic US monetary policy will work to raise the dollar exchange rate that will party offset the impact of tariffs on the US price level.

The folk memory of Smoot-Hawley and the Great Depression on economists and economic commentators

The strong reflex among economists and economic commentators that invites an assumption of chaos or disaster is historic memories of the Smoot- Hawley Tariff. This took effect in 1930. It started as an attempt by Republicans in Congress to introduce a modicum of protection to support agriculture in 1928. The legislation was widened into a wider general tariff. It was inflexible and expressed in cash rather than ad valorem terms. After the tariff was imposed the American economy went into a massive depression that contracted output by around a third. The Smoot-Hawley Tariff, was widely blamed as a major contributor to the fall in output and the international depression

Economists can exhibit a version of false memory syndrome in relation to tariffs and the Great Depression

Later research into this economic history significantly modified the perception of the economic consequences of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff. The main factors that led to the contraction of US output was the Federal Reserve’s decisions that contracted the money supply by a third over a three year period. This was explored by the great book of Milton Freidman and Anna Schwartz A Monetary History of the United States published in 1963.The contractionary effect of the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy was aggravated by the fiscal policies of the US Federal Government. Profesor Price Fishbeck in US monetary and fiscal policy in the 1930s in the Oxford Review of Economic Policy in 2010 surveyed public policy in the Depression era. He explains how the Revenue Acts 1932,1934 and 1936 all combined to raise taxes in an attempt to narrow the Federal Government budget deficit. The details of the tax increases operated to amplify other Federal policies, such as the National Industrial Recovery Act( NIRA) passed in 1933 that made US labour and product markets inflexible. These measures had the effect of fixing or raising prices and wages when the price level was falling as the American economy exhibited pronounced deflation, making it impossible for markets to clear.

Courtesy of Professor Douglas A Irwin we have a bible that explains the history of American trade policy. This is his book Clashing over Commerce : A history of U.S Trade Policy . Douglas Irwin summarises the position well. ‘The consensus among economists is that the Hawley -Smoot tariff played a relatively small role in either exacerbating or ameliorating the Great Depression. The effect of the tariff was almost certainly minimal in comparison to the powerful deflationary forces at work through the month tree and financial system. When compared to a decline in the money supply by one-third, even a substantial change in tariff policy is unlikely to have any significant macroeconomic effects, particularly when the duty bull imports were just 1.4 per cent of GDP.’

Contemporary US economic policy: fiscal expansion, defence spending tax cuts, deregulation, cheaper energy and technological diffusion

The context of the Trump administration’s tariff policy will be very different. In macro-economic terms there will be continued stimulus from a loose fiscal policy. President Trump’s agenda of tax cuts and higher defence spending will increase the Federal budget deficit. The micro-economic dimension of the Trump agenda will focus on radical deregulation and improvements in energy production.

The Trump administration will be governing against a background of economic transformation that will be in play independent of the policy actions of the Federal Government. This is continuing diffusion of technology and the effects of AI. This will work to stimulate both output and productivity.

Econometrics as an exercise in political hyperbole

The Wharton Economic model at the University of Pennsylvania projects that a trade war will lower US GDP by 5 per cent over twenty years and the IMF estimates that US GDP will be 1.6 per cent lower by 2026. Marieke Blom the chief economist at ING in an article in Financial Times entitled Beware risks of being too gloomy on Trump tariffs cogently explains the problems of being too pessimistic in forecasting the effects of tariffs. The forecasts that she draws attention to are implausible. In the same way that the British Office of Budget Responsibility’s projection of UK GDP being lower by 4 per cent after fifteen years, as a result of a Brexit is implausible. In the case of the UK and Brexit, for example, there has been no imposition of tariffs on trade in goods.

President Trump's agenda of tariffs will reduce economic efficiency, lower output and increase prices. The tariffs will involve the US economy being the principal loser in terms of reduced economic welfare. Yet exaggerating the likely effects of the policies in terms of hyperbole does not contribute to an understanding of the likely effects of the Trump administration’s trade policy.

The brutal changed geopolitical landscape: the US and its friends have to adjust their policies to the emergence of China a the dominating super power, buttressed by possession of the world’s largest industrial base

In geopolitical terms the combination of Russian aggression and the continuing emergence of China as the world’s dominant and potentially dominating superpower in military terms has huge consequences for the US, the EU, NATO and their related allies such as Australia and Japan. The Russian Federation’s economy has been turned into an effectively functioning and financed war machine. China accounts for around a third of world industrial output.China now enjoys genuine advantages in certain military technologies. China, moreover, has repeatedly demonstrated a capacity to introduce new technologies and produce them on a mass scale at a cheap price. We have seen this with solar panels, batteries and electric vehicles.

China’s trade in goods reflects the scale of its industrial capacity which buttresses its military capability

President Biden takes a back seat to President Xi of China at 2024 G20 Summit in Brazil

An aggressive sabre rattling Russian Federation already effectively at war on Europe’s border and a determined and assertive China will involve a huge defence response by the West led by the USA. China’s presence at the recent G20 Summit in Brazil, and the deference shown to President Xi by Latin American states reflects the politics of South America and the scale of economic investment of China. China’s $3.5 billion investment in new port facilities in Peru that will transform shipping from South America’s Pacific coast to China, dwarfed President Biden’s $65 million anti drug helicopter equipment programme in the regions.

The choreography of the G20 conference reduced President Biden and the US to appearing to be bystanders. The President took a back seat in contrast to the central role played by President Xi. The G20 was an illustration of Mrs Clinton’s conversation with the Chinese foreign minister when she was Secretary of State. The gist of it was that she would have to accept that China is a big country and America is smaller. In strict geographical territorial terms that may be inaccurate but in terms of political, economic, industrial and effective military capability it was a statement of uncomfortable truth for the US. The EU and UK should not for example occupy identifying items, such as Harley-Davidson motorcycles, Zippo lighters, Levi jeans and bourbon, to irritate the US as much as possible. It will be fruitless and only damage their own consumers.

America as an arsenal of democracy with its allies footing their share of the bill

President Trump’s administration will lead the American and western response to this geopolitical change. It will require a huge deployment of resources to facilitate a military build up. It will involve the remobilisation of America’s military industrial complex and the recreation military production capabilities in Australia, Canada, Europe, and the UK. Given the starting point of high energy costs in the EU and UK, the full deindustrialisation of the British economy and their respective employment and social costs, the bulk of the re-armament and industrialisation will be in North America led by the USA. America will have to take on the role of being the arsenal of democracy as it was in the 1940s. The difference between now and the 1940s America will expect European and other allies to pay to procure defence equipment and for the war materials and other industrial products they need. It will not be a replay of Lend Lease in 1941 or the Marshall Plan in 1948, and living off American ‘tick’. President Trump assisted by the General Accountability Office will be keeping a tab.

This big change in political and defence priorities will involve a huge shift in resources and economic priorities. Conventional notions of economic welfare and Paretian optimality are redundant in a geopolitical context where economies are seriously preparing for war with the purpose of avoiding conflict through effective deterrence. The main vehicle for policy will be public expenditure on defence and strategic materials. It will principally be financed by government debt. This will certainly be the case in the USA, but also in other economies such as Germany and the UK. The German constitutional debt break will have to be abandoned.

Rearmament on an industrial scale, impediments to trade, and heavy debt market borrowing by the US Treasury Department will provide a strong structural fiscal impulse in the years ahead. The international market in credit ‘risk free’ assets - government bonds - is huge, over $50 trillion. The US has the scale to shift the international flow of funds and raise long-term bond yields in a way that other smaller open economies such as the UK cannot. This will result in a portfolio effect where investors demand a higher risk premium for holding long-term government debt to reflect higher inflation risks. The combination of strong demand and an increased risk of inflation will support prices of real assets and equities as inflation hedges.

The return to war finance through debt

There will be plenty of demand for US Treasury debt among international investors and as its yield rises that demand will be further supported, because it will be more attractive to investors wanting a safe haven. US the full resources of the American economy to service its growing debt will expand with the debt. The combination of deregulation, an expansion of domestic oil and gas production and the growing productive potential of technology and AI will support the economic and financial capacity. This will be further supported by the continuing albeit eroding role of the dollar as the world’s principal reserve currency. The likelihood is that the combination of strong demand in the economy, higher US bond yields, strong equities and weakening foreign exchange rates in response to higher tariffs will support the dollar.

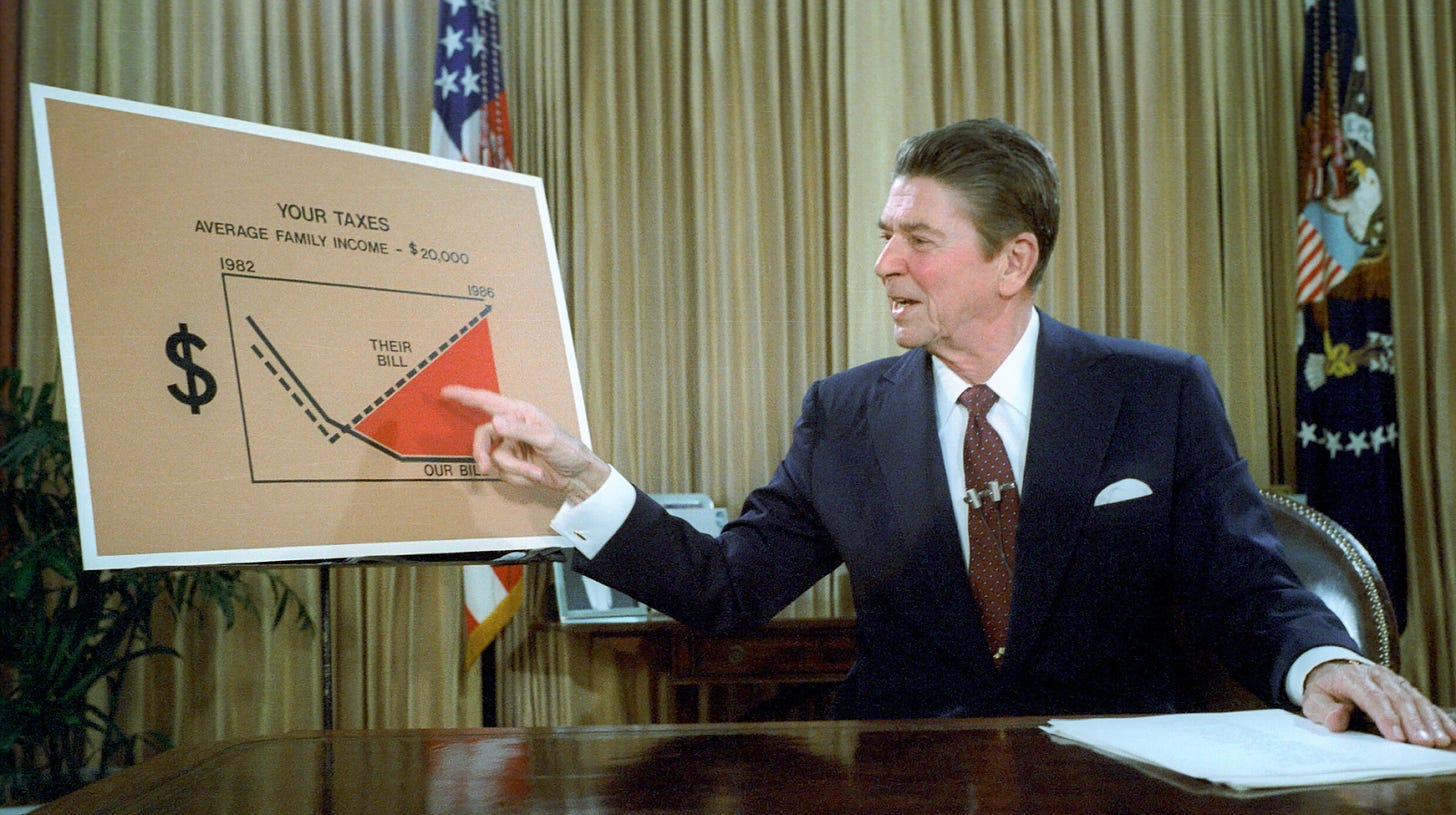

President Reagan explains the Economic Recovery Tax Act 1981 in a broadcast from the Oval Office in the White House in July 1981

Back to President Reagan’s War Keynesianism

In many respects this is a return to what the New Republic magazine in the 1980s called ‘War Keyensian’ in 1981. President Reagan announced big tax cuts and large increases in defence spending with little in the way of offsetting reductions in domestic Federal Government spending. This created a large structural Federal budget deficit. The combination of a disinflating monetary policy being applied by the Federal Reserve under the leadership of Paul Volker between 1981 and 1982 led to very high nominal and real interest rates. The US had no difficulty in selling its debt at a price, getting inflation down and establishing a long period of economic expansion. The difference today is that American economic policy will not be ornamented by President Reagan’s persuasive rhetoric about unimpeded free markets and trade; and the US economy does not have an acute inflationary hangover in the way that the American had after the Carter years and the 1970s. There is one element of common ground between President Trump and President Reagan. While President Reagan may have delivered the case for free trade and comparative advantage, more eloquently than any other occupant of the White House, in terms of practical trade policy, use of tariffs, quotas and export controls combined with extraterritoriality. President Reagan protected cars, steel, textiles and apparel. Douglas Irwin noted, for example.The share of imports covered by some form of trade restriction, after rising from 8 per cent in 1975 to 12 per cent in 1980, jumped to 21 per cent in 1984. The Reagan White House had more in common with the Trump administration than many people now remember.

Warwick Lightfoot

22 November 2024

Warwick Lightfoot is an economist and was Special Adviser to the Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1989 to 1992.