Understanding the Nationalist Republic of China and its legacy in Taiwan, helps the appreciation of modern Chinese economic and political culture

Modern historiography helps us get a better purchase on contemporary China by identifying continuities between political regimes, too long obscured by revolutionary and ideological hyperbole

The Kuomintang nationalist party in its conduct of government on the mainland of China between the 1920s and 1940s offers an insight into contemporary China. In trying to understand the ambitions and purpose of modern China, too much emphasis has been placed on examining the Chinese Government through the prism of the Chinese Communist Party and Mao Zedong’s Marxist-Leninist legacy which is probably an impediment to understanding.

China’s consistent determination to modernise

China is determined to be a modern, strong and assertive power. This has been central to the political agenda of China’s leaders for more than 130 years. It was at the heart of the modernisation agenda of the last decades of the Qing Dynasty, the revolutionary movement that emerged in the 1890s and overthrew China’s final Qing Dynasty and with it 2,000 years of Imperial government in 1912. The governments of the Republic of China and the Kuomintang led by Chiang Kai Sek and the Chinese Communist Party led by Mao Zedong after 1949, share critical elements of continuity and common purpose that have been obscured by revolutionary change and ideological hyperbole.

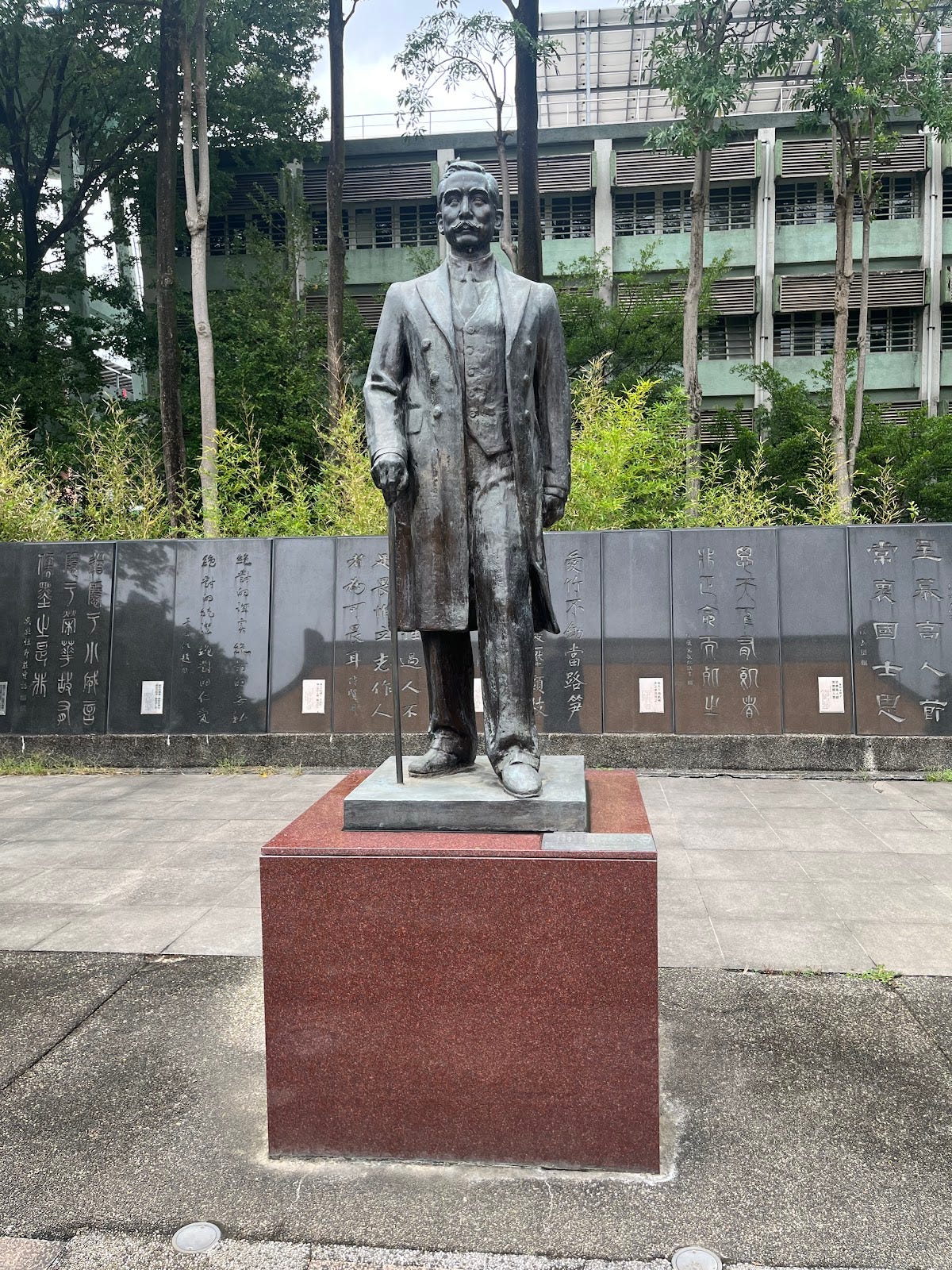

I travelled to Taiwan to try to learn more about the specifically Chinese nationalist republican tradition of the Kuomintang. Visiting the Sun Yat Sen Memorial Hall, the Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall, Chiang Kai-shek’s house in the woods on the outskirts of Taipei and the Office of the President of the Republic of China. They help to offer a sense of what a non-Communist Chinese political sensibility is.

Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall Guarding the Memory of Nationalist China

Republic of China guards the memory of Chiang Kai-shel

When I returned home my interest in nationalist China had increased and I read Jung Chang’s Big Sister, Little Sister, Red Sister Three Women at the heart of Twentieth Century China. It offers a vivid flesh and blood account of the revolutionary aristocracy of the Republic of China. By serendipity one of the editions of the New Statesman waiting for me at home contained an advertisement for a new book by a French historian Xavier Paules The Republic of China 1912 to 1949 published by Polity. It sheds helpful light on the questions that my visit to Taiwan had stimulated.

President and Mrs Chiang Kai-shel’s house in the woods on the outskirts of Taipei

Maoist years 1956 to 1976 distort understanding of China’s 20th century political evolution

Xavier Paules offers a synthesis of modern historiography and modifies, indeed contradicts much of the perspective on 20th century Chinese history generated by historians overly influenced by the Communist victory in the civil war in 1949. He describes this bluntly as a leftist perspective. He argues that as the Maoist years between 1956 and 1976 recede they are increasingly seen as ‘a diversion’ within a long-term process that started in 1900.

The Qing Dynasty’s audacious reform agenda

The idea that the Qing dynasty collapsed because it was sclerotic, incompetent, and incapable of responding to the challenges of necessary modernisation is misleading. After 1900 it embarked on a series of radical reform measures. The direction of travel of the New Polices proclaimed in 1901 was to create a modern constitutional monarchy with an elected parliament. The process of modernisation was exemplified by the abolition of the imperial Confucian examination system for recruiting the elite Mandarin corps of bureaucrats in 1905. The New Polices amounted to a radical overhaul of the functioning of the imperial state – modernisation of the law, education and the military. Change telescoped into a short period on a scale that would meet Sir Geoffrey Elton’s criterion of amounting to nothing less than a ‘revolution in government’.

The reforms were audacious in scale and involved a huge fiscal burden at a time when the imperial exchequer had just given up significant tax revenue because of a decision in 1906 to end the trade in opium aggravating its financial problem. They provoked opposition. As a precursor to building a parliamentary monarchy provincial assemblies elected on a narrow property-based franchise were elected in 1909; a network of 900 local chambers of commerce was established; new military forces led by a professional officer class were created after 1901. These institutions stimulated the growth of dynamic and politically ambitious local elite leaders that turned on the Qing Dynasty that had brought them into existence. These beneficiaries of the Imperial modernisation agenda organised, financed and supported the revolutionaries in 1911 and 1912.

An Imperial regime brought down by unpopularity of an ambitious programme of change

The collapse of the Qing Dynasty is not unlike the revolution that engulfed the Ancien Regime in France in 1789 where a faltering monarchy embarked on a programme of liberal reform where the process of change provoked opposition that was fatal for its political future. The big difference between the collapse of the Chinese Qing dynasty and the French Bourbon monarchy was that the events in 1912 were much less violent. The Chinese Emperor abdicated, and the Imperial clan continued to live in the Forbidden City and were supported financially by the Republic at considerable cost for a further twelve years.

The Republic of China proclaimed in 1912 took on the ambitions to create a constitutional parliamentary system with all the Qing dynasty’s ambitions for educational, legal reform. industrial and military modernisation. The revolution in 1912 was a profound rupture ending a 2,000 year dynasty. There was no turning the clock back or chance of passing the Mandate from Heaven to a new dynasty. Yuan Shikai, the modernising Qing official and the last Imperial Cabinet Prime Minister, discovered this when as the second provisional president of the republic, he announced the restoration of the imperial government in December 1915 as the Hongxian Emperor, only to be forced to renounce the restored Imperial system in March 1916.

The Republic of China’s parliamentary tradition

The republican constitution agreed in 1912 was firmly parliamentarian and modelled on the French Third Republic. The executive powers of the president were carefully constrained given that representatives of the provincial assemblies feared the ambitious, charismatic Yuan would take office as president. Song Jiaoren campaigned against Yuan emphasising his concern about his personal ambition, desire to return to an imperial system and he also shared the concern of other Chinese politicians about Yuan’s financial management. Sun Yat Sen’s original revolutionary instrument, the United League founded in 1905, was turned into a political party the Kuomintang for the parliamentary election in August 1912.

This transformation was brought about by Song Jiaoren. He removed the radical elements of the United League’s revolutionary programme and created a popular moderate party, drawing in other parties. Song Jiaoren committed the Kuomintang to decentralisation or federalism, which appealed to provincial elites. This moderation attracted support from upper class gentry, landowners and merchants. This was politically astute, given that only ten percent of adult Chinese men, around 40 million people could vote. In the process Sun Yat Sen became politically marginalised.

The Kuomintang triumphed in the elections held in the winter of 1912-13 obtaining majorities in both houses of parliament. Song Jiaoren, the organiser of the Kuomintang emerged as the elected politician, who was expected to wield effective political power as leader of the Kuomintang majority in parliament and to emerge as prime minister.

Political violence and authoritarian leadership

This ambition and the hopes of a smooth evolution to a western parliamentary democracy were brutally halted. Song Jiaoren was assassinated in March 1913. It is not clear who was responsible for Song Jiaoren’s murder. Many people assumed it was President Yuan. The former provisional president San Yet Sen, for example, publicly blamed Yuan. Yet Song, who survived for two days after being shot, at Shanghai railway station did not blame the provisional president for it. Nor did most other Nationalist politicians blame Yuan. Jung Chang by implication suggests that Sun Yat Sen had a motive to remove Soong because he had pretty much eclipsed Sun Yat Sen as an effective politician with a role in the new republic. Sun Yat Sen recognised this himself when he removed himself from active politics and said that he would concentrate on building China’s railway infrastructure. Sun insisted on blaming Yuan and instigated the first armed rebellion against the provisional president. As Jung Chang comments ‘This, the first war in the infant republic, unleashed decades of bloody internal strife. The ‘Father of China’ was the man who fired the first shot.’

In 1947 Chiang Kai-shek proclaimed a new democratic constitution. This was necessary for several reasons. Against the Communist military threat, the Kuomintang had to appear to have a veneer of democratic legitimacy to retain American political and military support. It was also politically important for Chiang Kai-shek to appear to conform to the road map set out in Sun Yat Sen’s writings, a legacy that Chang had turned into a personality cult since his death in 1925. The constitution was distinguished by a huge expansion of the electorate and the adoption of universal suffrage. Yet as Xavier Paules observes the elections ‘were not a model of their kind since they featured, in particular, a system of official candidacy somewhat reminiscent of the French Second Empire.’ The elections for parliament were held at the end of 1947 and in January 1948. Chiang was swiftly elected President of the Republic by parliament and once that was accomplished parliament was suspended and all powers were handed to the president.

Chiang Kai-shek’s legacy in the continuing Republic of China on Taiwan

When Chiang Kai-shek retreated to Taiwan in 1949 this constitutional edifice remained in place along with the authoritarian hand of the executive and the Generalissimo President Chiang himself. The same National Assembly elected in 1947 continued to sit for over 40 years. From the time that the Kuomintang reoccupied Taiwan after the Japanese surrender in 1945 the Republic of China had taken a tough line on dissent. The president often interfered with judicial proceedings with the result that more condign criminal law and punishment was applied. There was, moreover, plenty of dissent about the new regime.

Tableau recreating Chiang Kai-shek’s presidential office: Governing Taiwan

Taiwan had been ordered and well run during the Japanese colonial occupation between 1895 and 1945. There had been a lot of economic development reflected in the construction of roads and railways and the new regime disrupted this. Martial law remained in place until 1987. The legacy of Chiang Kai-shek himself in Taiwan remains highly controversial and contested. This is now illustrated at the Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall with art installations commemorating protestors who took their own lives in opposition to the Kuomintang’s authoritarian government tradition

Chiang Kai-shek’s legacy in Taiwan is controversial

This contention is reflected in modifications made in recent decades to the formal memorial hall constructed in his memory. While the notion of a Chinese parliament has been a consistent feature of the political Nationalist culture of the Republic of China, even in modern democratic multi-party Taiwan there is an executive orientated constitution with power concentrated in the hands of the President.

Presidential Palace Taipei

Taiwan now enjoys a lively democratic culture with contested multi-party elections and an open and engaged civil society.

Contested elections in Multiparty Democracy Taiwan

An active civil society inviting constitutional and law changes

While the intellectual and commercial elite of China remained on the mainland, Chiang Kai-shek took over 2 million supporters including 500,000 soldiers with him to Taiwan in 1949, in a carefully logistically planned evacuation. The experience of shifting economic assets and indeed the location of the capital that the Republic of China had during the Japanese wartime incursions in the 1930s and 1940s, was fully used in the retreat from the Communist CCP controlled mainland of China. The Republic of China’s gold and foreign exchange reserves were all removed to Taiwan. The best-known example of this removal of objects and material in the face of the enemies of the Nationalist Republic is the transport of thousands crates of artistic treasures from the former Imperial art collection in Beijing. The catalogue of the National Palace Museum in Taiwan, Splendours of the National Palace Museum explains that in 1924 the Republic of China nationalised the Imperial art collection and was placed in a new Museum inaugurated on 10th October 1925, the National Day of the Republic.

National Palace Museum ROC Taiwan

After the Mukden Incident 1931 the Museum in preparation for the likely Japanese occupation removed its collection to Nanjing. 2,972 crates of the collection originally from the Forbidden City and a further 852 crates from the Preparatory Office in Nanjing were removed to Taiwan in 1948. This transported art collection forms the basis of the National Palace Museum opened in Taipei in 1965.

Meat-shaped Stone, jasper carved into the shape of a piece of Dongpo pork, one of the most popular object in the National Palace Museum Taiwan

Jadeite Cabbage from the Eternal Harmony Palace of the Forbidden City now at the National Palace Museum in Taiwan

The Kuomintang as custodians of Sun Yat Sen’s modernisation legacy

Xavier Paules in his assessment of Chaing Kai-shek’s nationalist republican legacy concludes that the Generalissimo had pretty much applied Sun Yat Sen’s programme ‘with a remarkable fidelity and a certain degree of success’.

Sun Yat Sen whose personality cult guided the KMT

Paules identifies the assertion of the power of the central government over the warlords, the abolition of the unequal treaties as examples of this success. In the economic arena in the 1940s the Chinese state had acquired a large public sector, a process that conformed to Sun Yat Sen’s thinking. The concentration of power in the hands of the president as a form of personal rule, in Paules judgement was an example of where Chaing Kai-shek derogated from Sun Yat Sen’s template. Chaing’s abandonment of mass mobilisation and his militarisation of Chinese society is in Paules view an even greater break with the Sun Yat Sen legacy. A lack of effective representative institutions based on popular election, huge executive powers invested in the head of the executive or state and an authoritarian government that emphasises the role of the armed services and national security in all aspects of society are all common to both the Kuomintang’s Nationalist Chinese Republic between 1927 and 1949 and the Communist Peoples’ Republic in place since 1949.

The Republic’s success in building China’s nationalist identity

The few Chinese entrepreneurs or academics left the Chinese mainland to go with Chaing Kai-shek to Taiwan in 1949. Paules describes their decision to remain in China as a positive decision to stay to construct a future successful China. He explicitly rejects the notion that they were naïve or harboured illusions about CCP, drawing on their diaries and private correspondence to argue that they accepted that their generation would have to be sacrificed to contribute to a national recovery. It represented a sense of national development over the previous sixty years.

A similar sense of personal national mission and recovery informed the reforming officials of the Qing Dynasty in the last twenty years of the monarchy. A similar patriotic zeal informed Sun Yat Sen and his colleagues when they set up the Revive China Society and called for a republic in 1894. The republican agenda was explicitly nationalist rejecting the Manchu Imperial elite of the Qing dynasty, illustrated for example by the cutting of the queue in 1912 – a sort of pigtail haircut mandated by the Qing dynasty when it took power in the 17th century.

The decades of republican government contributed significantly to Chinese nationalist feeling. Once the republic was established in 1912 an important part of the Kuomintang’s agenda was modernisation and improvement. On his death in 1925 Sun Yat Sen left a legacy agenda set out in his Last Will which included The Plan for National Reconstruction, The Fundamentals of National Reconstruction, Three Principles of the People and The Manifesto of the First National Congress. This sense of purpose in modernising and asserting China’s place in the world was a mission that Chaing Kai-shek and his Nationalist party doggedly stuck to in the Republic of China. It is also a central part of the sensibility of the Communist regime that flowed the Kuomintang after 1949. The strident assertion of Chinese wolf warrior diplomats and of Chinese students is consistent with a tradition of popular state building that can be traced over 130 years. It is, moreover, embodied in the political persona of the present President of China.

Communist planning and the legacy of economic autarky in the Republic of China

Sun Yat Sen believed that heavy industry was critical for Chinese modernisation and development. In the 1930s the role of the state in the economy became much greater. This partly reflected the response of the Republic of China to the Japanese invasion and the demands of a wartime economy. Between 1937 and 1940 639 companies and 60,900 tonnes of industrial equipment were relocated to western China as the Japanese advanced. The main sectors involved were steel, chemicals and mechanical engineering, the kind of strategic industries vital for wartime.

The state also became much more assertive in economic affairs reflecting the autarky deployed in Germany by the Nazi Government. This included planning, centralised management of use of materials and the development of state-controlled industries. At the start of the Sino-Japanese war, the role of the state in industrial production was limited and confined to heavy industry. As the war progressed the scale and range of public sector enterprises increased. State enterprises developed paternalistic practices that gave employees housing, health care and childcare. The end of the war, if anything, increased the role of the state in the economy in the Kuomintang republic. After the war Japanese property and businesses were expropriated by the state, as was the property of Chinese businesses that were considered to have collaborated with the Japanese occupation.

Xavier Paules considers that the administrative foundations for the economic planning of the 1950s were laid down during the last decade of the Republic under the leadership of the Kuomintang. Apparently, many of the officials involved in managing economic policy in the 1930s and 1940s remained in place during the new Communist regime. Moreover, Paules draws attention to the fact that the first five-year plan of the Communist government was largely based on the five-year plan for reconstruction drawn up by the Kuomintang nationalists in 1945. Today state enterprises account for about 65 percent of Chinese GDP, their place in the economy is not unlike many of the government controlled businesses in the 1940s.

Continuities between regimes -a shared assertive authoritarian nationalist culture

In Xavier Paules' conclusion he identifies dimensions of continuity between the nationalist Republic of China and the People's Republic of China today. Both the nationalist Republic and the People's Republic share a determination to modernise by being open to the west, which is considered the reliable road to power and national assertion. In both regimes the government is managed by a pragmatic one-party state that has abandoned its former radical revolutionary tradition. Today China is an authoritarian regime, but no longer a totalitarian regime as it was during the Mao Zedong period of radical experiments. China’s leadership is stridently nationalistic and invokes a version of Confucian moral communal purpose. It is not at all clear that if the Kuamintung had continued to govern China that it would be fundamentally different in its national aspirations than the contemporary mainland Chinese Government.

Warwick Lightfoot

15 January 2024

Warwick Lightfoot is an economist and was Special Adviser to the Chancellor of the Exchequer between 1989 and 1992.

In the first two decades of the 21 Century, he had the opportunity to meet Chinese bank economists and executives and many official delegations from provincial Chinese administrations, cites and institutions of the People's Republic of China such as the Upper Chamber of the Chinese legislature. These meetings greatly benefited by being facilitated by professional interpreters and helped to stimulate an interest in trying to better understand the economic and political culture of China.