UK’s Spring Economic Statement focuses on Redundant Fiscal Rules, Neglecting falling Productivity, Profits, the falling Rate of Return on Capital and Structural Problems from higher Public Spending

UK has supply-side problems arising from high public spending, taxation and labour market regulation that deliver weak productivity and falling profits

Macro-economic policy in Britain continues to focus on a set of economically redundant fiscal rules. UK productivity has been revised down. Profits in national income are falling along with the rate of return on capital. Policy makers should be interrogating the crowding out effects of public spending on the private sector, and how both high marginal income tax rates and a rising minimum wage in relation to average earnings affect work incentives.

The Spring Statement complied with the obligation that HM Treasury has under the 1975 Industry Act to publish two economic forecasts a year, in the context of a full Budget Statement accompanied by an economic forecast, that is now delivered in the Autumn.

The focus of comment on the Spring Statement was on the extent that developments in economic data since October 2024, would result in the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rachel Reeves being in breach of the revised and arguably strengthened Fiscal Rules that were set out in the Autumn Budget in October 2024, by the Chancellor. Whether the fiscal rules are complied with, is assessed by an independent body the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR).

The key propositions in the rules are that current government spending should be financed by taxation and borrowing should only be used to finance capital investment and the stock of public debt should be falling by the end of the forecast period.

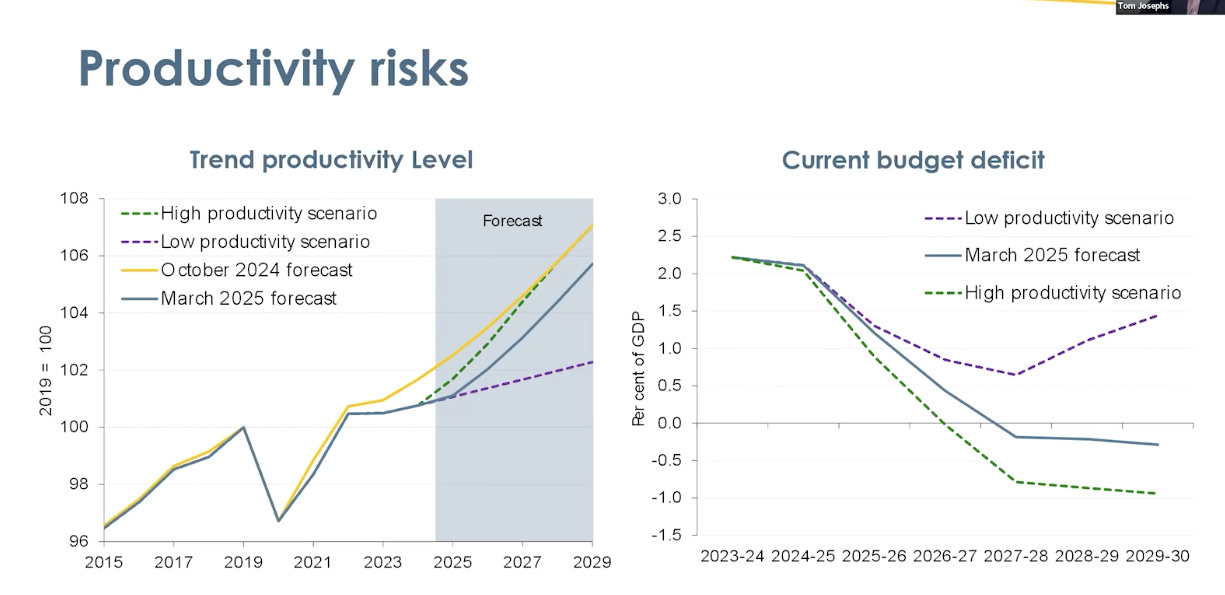

Three developments threatened a breach of the Chancellor’s revised fiscal rule. Higher international bond yields have raised long-term government debt management costs since October 2024.These have increased UK debt service charges by around £10 billion. Higher energy costs and higher inflation are expected to depress GDP growth compared to the OBR’s Budget economic forecast made in October 2024. Revisions made to data on productivity by the Office of National Statistics have lowered the level of GDP. There was also data from the National Accounts figures and from surveys of business and consumers that suggested economic activity was slowing. Upward revisions to population without an upward revision to the level of GDP, mechanically lower productivity by about 20 per cent. This will lower output in the near term. Although the ORB's economists do not think it will necessarily proportionately reduce trend productivity in the medium term, it may still permanently lower it.

The result is that over the forecast period the ORB's estimate of growth is lowered . In 2025 it is halved from 2 per cent to 1 per cent. Growth then picks up, and accelerates as output mechanistically returns to its trend rate of growth within the OBR forecasting model. In the same way that it used to do in the Treasury Economic Model. Yet, overall the OBR expects cumulative growth over the forecast period to be 0.5 per cent lower than it was forecasting in October, between 2023 and 2029

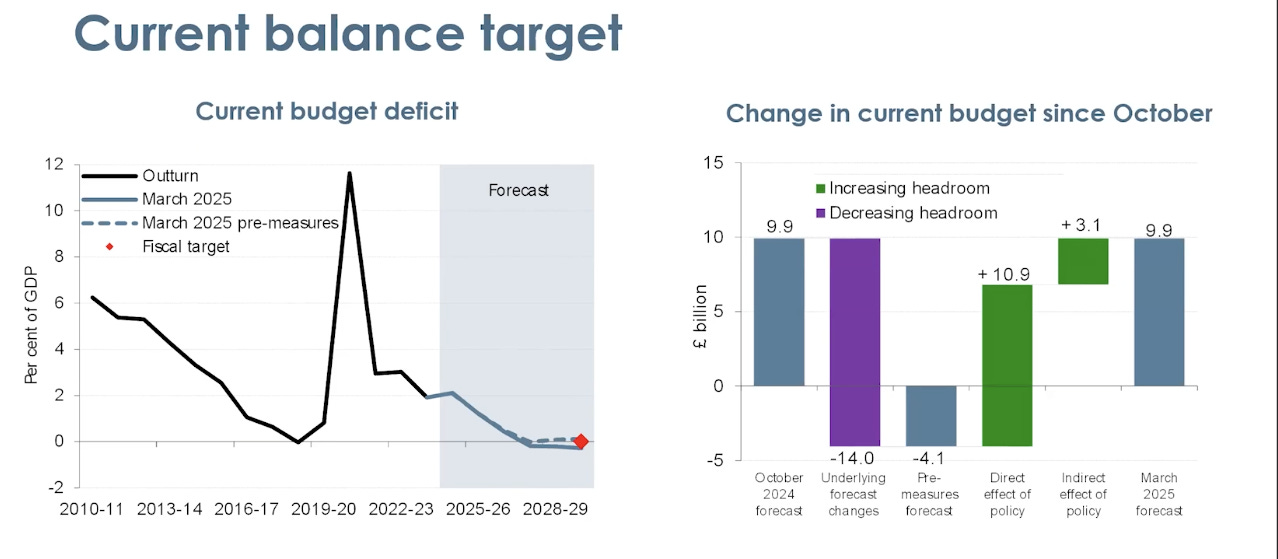

Changed forecasts for expenditure and tax receipts had an effect on whether the Chancellor would not meet the fiscal rules. Without discretionary measures the fiscal rules would have been breached.The Chancellor reordered public expenditure to accommodate higher defence spending, raise tax compliance and to cut expenditure on social security transfer payments.The OBR estimated that these measures in combination were sufficient to meet the fiscal rules.

Chancellor has taken measures to ensure that the Treasury meets the fiscal rules

Among the Government’s policy responses to weakening economic activity were reform to the planning system, principally relaxing building controls in green belts around cities. The OBR estimates that these changes to planning will increase house building by 170,000 units.These ‘indirect effects’ of policies to improve the economy's supply performance have been incorporated by the OBR into its formal economic forecast. The planning reforms raise economic activity, increasing GDP and with higher GDP there are higher tax receipts. Lower spending on overseas development aid, changes to welfare benefits which were reduced by £5 billions and the improvements in the supply-side coming from planning reform, in combination cover the shortfall in the public finances that would have caused the Chancellor to breach the rules. A large part of the discretionary adjustment comes from ‘indirect effects to improve the supply potential of the economy.’

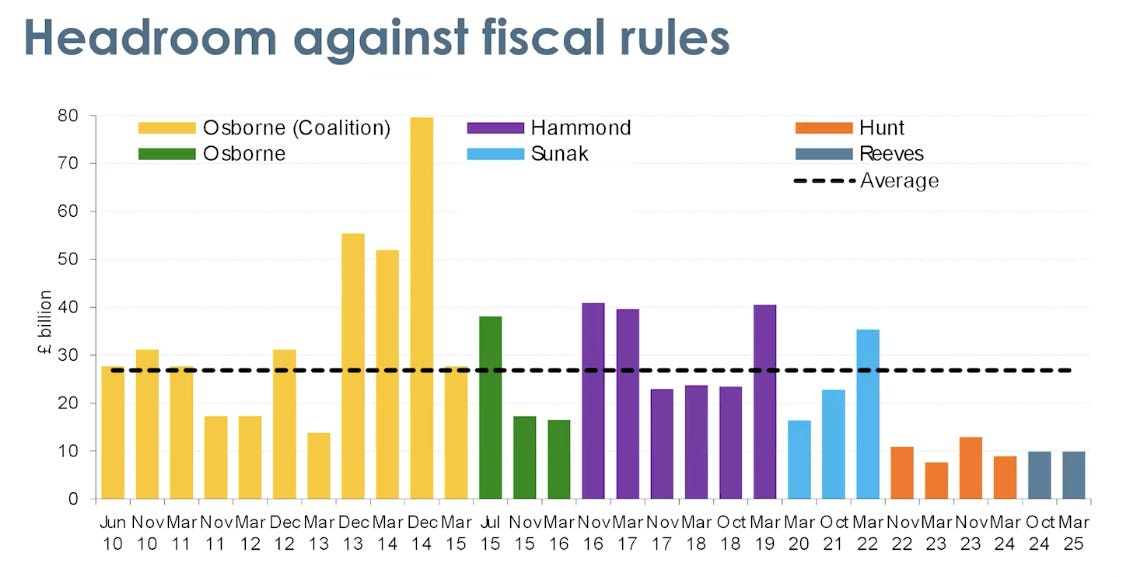

Chancellor’s ‘head room’ under the fiscal rules is close

The OBR forecast shows falling borrowing as planned in October over the five years results in the current budget rule being met by a margin of £9.9 billion. This co-called ‘head room’ is tight against the fiscal rule - about a third of the average of that previous chancellors had since 2010 when the OBR was set up and is modest in relation to the risks that attach to any economic forecast..

One of the principal risks to the OBR’s economic forecast is weak productivity. Productivity in the UK economy has been consistently weaker than the OBR’s economic forecast. It fell after the banking crisis in between 2007 and 2009 and in the Great Recession and has not recovered. Moreover there has been further disappointing news on measured productivity arising from the ONS’s latest revisions to it.

Population and employment estimates have been revised by the ONS. The ONS revised labour supply more than it revised GDP. That pushed down measured productivity by about 1.5 pct. The OBR estimates that this will result in short term effects, such as volatility in data, spare capacity and measurement issues and there will be some bounce back. However this revision represents a large fall in the level of productivity.

The OBR has identified risks to its economic forecast

The OBR highlights a series of risks to its forecast that may result in the fiscal rules being breached. They are divided into. Those risks that have been partially mitigated by the discretionary actions of the Chancellor and those that remain. The risks partially addressed in the judgement of the OBR are defence spending, health related welfare spending and a tendency for policy to exhibit an asymmetry where better numbers result in higher spending but a deterioration in the fiscal position is left uncorrected. A notable feature of the Chancellor’s response to the changes in outlook since the Autumn is to take action to meet the rules, a symmetrical response from the perspective of the OBR.

The UK’s fiscal rules are economically redundant

The difficulty with the British Labour Government's fiscal rules is that they address a secondary issue in public finance. This is the choice between how public expenditure is financed between taxation and borrowing. It is a continuation of the same defective policy focus of the previous Conservative Government led by Rishi Sunak. The rules artificially permit borrowing for investment and discriminate against current expenditure in a manner that is not persuasive. The benefits of the public sector’s capital stock are not realised without adequate current spending. The school science laboratory is of little use without a chemistry or physics teacher. In the same way a hospital building cannot function without doctors, nurses and all the professions allied to medicine being in play. The rules, unless set aside, prevent macro-economic policy from responding to adverse shocks. Raising taxes and cutting expenditure to meet a fiscal rule as an economy slows, amounts to a procyclical tightening in demand, suppressing the fiscal impulse to demand when it is probably needed. Moreover, the rules fail to cap public expenditure or ensure that it falls over the economic cycle. They merely focus on borrowing. They are capable of being met with both a rising tax burden and a rising ratio of public expenditure to national income. The rules are not framed to address the structural effects of a rising public expenditure ratio within GDP

Focus on redundant fiscal rules distracts attention from the debate that the UK needs to have about public expenditure.

Redundant fiscal rules distract attention from the interrogation of more pressing issues. Instead the focus on government borrowing results in the neglect of how much more significant matters of how much is spent by the public sector, how effective is public spending and the extent that spending is financed with least deadweight cost. The fiscal rules are a distraction from sensible policy development. How disability benefits, such as Personal Independence Payments are structured and reformed should not turn on a myopic discussion of how they can be lowered to accommodate a Chancellor who needs to meet a redundant fiscal rule.

There is a high degree of continuity between the policy agenda of the last Conservative administration and the present Labour Government. Monetary policy is set by the Bank of England against an inflation target, there are a set of clumsy fiscal rules that focus on borrowing, a belief that the way to increase economic growth is to raise business and public sector investment.

In the Budget in October 2024 the Labour Chancellor raised government spending and taxation. The chosen discretionary tax increased, such as changes to reliefs for agricultural and business assets in Inheritance Tax and increased employers National Insurance Contributions were ill chosen increasing the deadweight costs of taxation. The Spring Statement does not modify these budget decisions. The decisions that Labour ministers took after taking power to accommodate public sector pay pressures have further aggravated the cost of public expenditure.

Like their Conservative predecessors, Labour ministers emphasise business investment and public infrastructure investment. There is too little curiosity among British policy makers about the rate of return on both private and public sector investment in the UK. The OBR believes that public investment has a rate of return of 10 per cent, which is the same as the average rate. Given the bureaucratic and political processes involved in public investment and the difficulty of combining current and capital spending decisions in a coherent manner, and the inherent difficulty that there is in estimating public investment returns that may be optimistic. The National Infrastructure Commission, for example, has been minded to move away from a narrow focus on the rate of return on investment to a broader and more elastic concept such as ‘amenity’. The difficulty of basing public investment on amenity value, in a context where public capital accumulation is identified as central to raising the trend rate of growth, is that amenity does not of itself economically increase the trend rate of growth of the overall economy.

UK profits within GDP and the rate of return on business investment are falling

An interesting chart in the OBR’s economic forecast shows a fall in profits as a share of GDP over the last ten years. Profits have fallen and are forecast to fall further to 14.3 per cent of GDP in 2025. This is a fall of almost two percentage points in the profits ratio since 2019. The profits ratio within GDP is expected to be 11.7 per cent lower. The OBR points out that this is a return to the level of profitability last seen after the Great Recession in 2010. The OBR also noted that ‘the net rate of return on business sector capital has also been on a steady downward trend, from 12 per cent in 2015 to 9 per cent in the first half of 2024’. OBR expects profits to be further squeezed this year by rising wages that are increasing faster than productivity, inflation and higher employer National Insurance Contributions.

Time for policy makers to focus on what shapes the UK’s supply-side performance

The UK needs a debate about the efficiency of its capital stock in both the private and public sectors instead of a collectivist glee club that sings for more private and public investment spending. The discussion of fiscal policy should focus on the crowding out effects of an expanding public sector on private sector economic activity and the aggravated deadweight costs of the present structure of marginal income tax rates created since 2010. The Manhattan Skyline of marginal tax rates in income tax do not reflect a person’s position in the earnings distribution. Margin tax rates hit 60 per cent for people with children as Child Benefit is tapered away at £60,000 then they fall back to 40 per cent then hit 60 per cent when the personal allowance is tapered away at £100,000 before falling to 45 per cent. The Economist reports that there are now estimates of 10,000 taxpayers arranging their affairs to avoid being exposed to the withdrawal of allowances at £100,000 by working less.

The UK’s fiscal debate needs to explore these high marginal tax rates that phase in and phase out as peoples’ earnings rise, having malign effects on labour market incentives. The discussion about disappointing UK productivity should widen to take in this damaging structure of marginal tax rates for work incentives. It should also interrogate the effects of the minimum wage legislation that has increased the minimum wages to around 65 per cent of median wages at a time when productivity growth has been weak.

The focus of economic public debate on a myopic discussion about whether the Chancellor will or not comply with what are in economic terms, a redundant set of fiscal rules, is damaging. It obscures discussion about more pressing subjects, such as why is the UK rate of return on capital falling, how should its Manhattan Skyline of marginal income tax rates be reformed and how well is its labour market functioning in the context of the increasing importance of the minimum wage in relation to median earnings.

Warwick Lightfoot

31 March 2025

Warwick Lightfoot is an economist and was Special Adviser to the Chancellor of the Exchequer between 1989 to 1992