The Necessary, But Expensive Decarbonisation and the Green Tooth Fairy

Decarbonistion: a necessary process to be approached systematically with candid realism about cost and slower growth

The need progressively to accomplish decarbonisation has been clear since climate change and the role of carbon in the atmosphere, as its cause, was identified in the late 1980s. British Antarctic Survey Antarctic (BAS) ice cores reveal the clearest link between levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and the Earth’s temperature. They show that the temperature of the climate and the levels of greenhouse gases are intimately linked. In 2004. The BAS extracted a three-kilometre ice core from the Antarctic. This core contains a record of the Earth’s climate stretching back 800,000 years, providing the oldest continuous climate record yet obtained from ice cores.

The case for decarbonisation is clear

When you visit the BAS in Cambridge and look at the cores and the data plotted from them on display outside the room with the freezers where the ice cores are kept, there is a clear picture of increased carbon in the atmosphere that starts around 1790 when the Industrial Revolution took off in Britain. Plymouth Marine Laboratory (PML) pioneered the early climate change model and PML has led ocean acidification (OA) research, a term used to describe the continuing fall in ocean pH caused by human carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions that arises from the use of fossil fuels, since the term was first coined in 2003.

The need to reduce the emission of carbon dioxide to limit the increase in global temperatures is clear. The question is how countries carry out the change. Before 1790 most people were cold in winter, often hungry, travelled little and lived in the dark when the sunset in the evening. The use of fossil fuels with their malign externality, carbon emissions, has transformed the welfare of people fortunate enough to live in modern advanced market economies. It was never going to be either easy or cheap. Advocates of green policies have in many respects made the need to secure public support for the technological change needed more difficult to secure by asinine rhetoric about exciting new green technologies and exciting new jobs.

The challenge is awkward the targets are likely to prove unrealistic

The most efficient way in terms of thermal-physics and the cheapest way of carrying out many tasks requiring energy - travel across the Atlantic, driving a car across the US, heating a house or generating electricity - is to use technologies that involve emitting carbon and using materials, such as coal, gas and petroleum. Shifting to other technologies to accomplish these tasks was always going to be expensive and inconvenient. Moreover, policy makers have always needed to be alert about avoiding the premature scrapping of existing capital stock, at significant cost merely to obtain a marginal improvement in the reduction of a damaging externality, when waiting may enable greater reductions in emission by taking advantage of future progress in technology.

The UK Government has a target to achieve Net Zero carbon emissions by 2050, which is written into primary legislation in the Climate Change Act 2008. The UK Government in its Net Zero Strategy published in 2021 set an objective to decarbonise the power system by 2035. Given the time lags in planning, building schedules, without taking into account wider supply constraints and costs this will be difficult to achieve. A sustained direction of travel is likely to be of more use than a set of brittle and unrealistic targets. Not least because of the new pricing and regulation structures that will be needed to manage an energy network that is increasingly detached from marginal cost pricing.

The cost of decarbonisation will be expensive

William Nordhaus, the Yale economist writing in Reflections on the Economics of Climate Change in 1993, noted that ‘mankind is playing dice with the natural environment through a multitude of interventions – injecting into the atmosphere trace gases like the greenhouse gases or ozone-depleting chemicals’ He developed macro-economic models of climate change that show that the sectors of the economy that rely most on unmanaged ecosystems are heavily dependent upon naturally occurring rainfall, runoff, or temperatures–will be the sectors most sensitive to climate change, generally. These are the agriculture, forestry and outdoor leisure sectors. So, Nordhaus, a distinguished pioneer of the economic analysis of decarbonisation, is crystal clear about its necessity. He is also equally lucid on its inconvenience. In his book The Climate Casino Risk, Uncertainty, and Economics for a Warming World published in 2013, the year Nordhaus became president elect of the American Economic Association, he estimated the cost of limiting temperature increase to 2 per cent above pre-industrial levels adopted at Copenhagen would cost between 1 and 2 per cent of world annual income. Moreover, the fewer economies that participated and the less optimal the policy tools employed would raise these cost estimates.

Decarbonisation is a necessary and expensive process. There needs to be a price set for the emission of carbon and a carbon tax that obliges people emitting carbon to pay for the full cost of the externality.

The starting point for decarbonisation – apply orthodox Treasury advice on taxation and subsidies

At the start of the new green agenda in the 1990s the OECD did some helpful research. This argued that the starting point to decarbonise in public policy terms would be for governments to review existing policy avoiding artificial production subsidies and distorting tax expenditures. In other words, a more neutral tax system and ending attempts through public policy to maintain agricultural and manufacturing output.

In the UK context, the OECD guidance in the 1990s implies, for example, the application of the standard rate of VAT to domestic supplies of fuel and power, children’s clothes and food, the full reduction of agriculture and manufacturing production subsidies and a neutral income and corporation tax regime. All this should be done before policy makers occupy themselves with special carbon related policy measures, such as carbon taxes.

The easy bit of decarbonisation

By the middle of the 1990s in the UK most of the production subsidies in manufacturing had gone largely because of the privatisation of electricity and the ending of the subsidy for using coal in electricity generation and the privatisation of steel. In the UK the issue of tackling expenditure taxes and household consumption remains. As Professor Sir Dieter Helm the Oxford economist told the House of Lords Economic Affairs Committee British agriculture accounts for 0.5 per cent of GDP but around 11 per cent of UK carbon emissions, and much of this output continues to be supported by public sector transfer payments of one sort or another.

The costs of decarbonisation increase as progress is made on the necessary journey. There are initial easy reductions in emissions. Both Germany and the UK offer examples of this. In the two decades after 1990 their carbon emissions fell. This was largely because of a sensible set of policies that would have been carried even if carbon were not a damaging externality. In the German case it arose from the dismantling of the East German socialist command economy and its heavy industries. In the UK from structural economic change that continued the process of deindustrialisation and the privatisation of the nationalised industries such as electricity and coal and imposing a hard budget constraint on them that ended the subsidy that resulted in British mined coal being used in electricity generation. The result is that from accounting for over 75 per cent power generation in the mid 1980s it is now down to around 2 per cent.

The huge economic organisational challenge of moving from marginal cost pricing to network charges

The necessary further progress will be more expensive and technologically more difficult. Not only will it involve expense and technologies that are more awkward, but it will also involve complex issues in economic organisation, finance, regulation and market structure. Many of the green technologies such as the use of renewables like wind and solar and nuclear power involve both huge costs to establish, but little or no cost to deliver at the margin once established. This makes marginal cost pricing that is at the heart of most market transactions and was the model for pricing exemplified in successive UK nationalised industry white papers, redundant.

Government intervention is needed to secure public goods such as security of supply

Many of the technologies raise issues about security of supply both in terms of physical supply and in terms of cost to the consumer. This involves building in reliable margins of redundancy into energy supply that conventional markets and pricing would not do without public intervention, given that security of supply is essentially a public good that communities need. The decision by the British Government in 2017 to close the Rough gas storage facility was a mistake. The government decided not to give Centrica the money to keep it open.

The UK and other countries such as Germany now must do more awkward, expensive and inconvenient things if it is to make further progress on carbon reduction. Inane windy rhetoric about the excitement is not helpful any more than announced targets that are neither properly scored in relation to cost technological feasibility.

Renewables have a cost that their lobbyists ask for subsidies for

Substituting solar, wind, and nuclear power for coal and gas in electricity generation is expensive. If they were not, industrial lobby groups offering to provide wind, solar and nuclear power would not demand upfront subsidies from governments to provide finance for their investment.

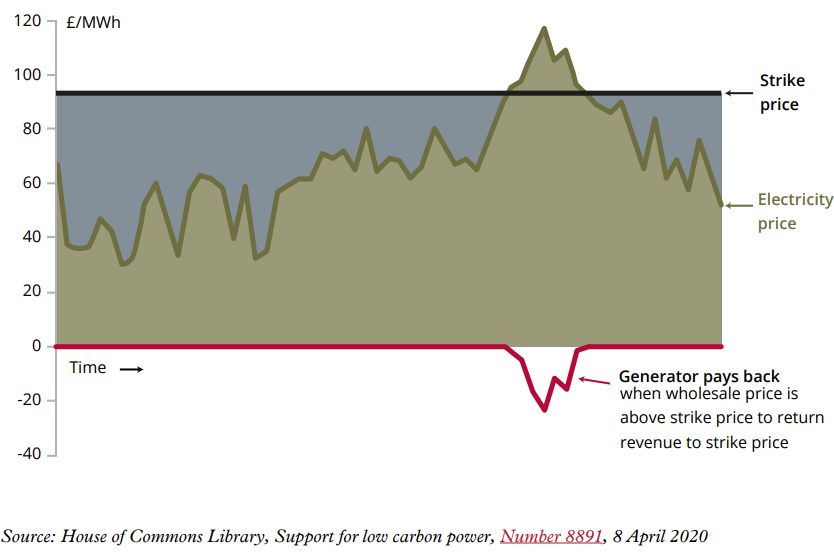

In the UK the heart of the strike price agreed by the government for the electricity is that which will be generated by the new nuclear power plant at Hinkley Point. It is the central issue in the pricing and auctions of contracts for difference that are organised by the British Government to support the green transition.

Brouhaha over alleged stingy subsidy in the UK round 5 renewable auction

A powerful example of this is offered by the latest- ‘round 5 auction’ - of Contracts for Difference CFDs in September 2023. It failed to bring forward any offshore wind production. The UK Government’s present objective is to deliver 50 gigawatts (GW) of offshore wind by 2030. This would raise the amount of electricity generated by it from 14 GW, an almost fourfold increase. Energy providers complain that the government subsidy was too expensive and that their costs have gone up. One provider that was awarded a huge contract of 2.6GW in 2022, Orsted for the Hornsea 3 CFD at a strike price of £37.55, is considering handing it back given the cost pressures it has. The CFD ensures a provider will receive a fixed minimum payment, the ‘strike price’, for the electricity generated by its assets. The firms sell their electricity to the grid in the normal way but if the ‘market’ price falls below the strike price the government supplements the payment. The strike price provides a guarantee for the provider that retains incentives to be efficient in the management of their assets. The present brouhaha between the Government and energy suppliers turns on what is a reasonable strike price given the increase in project costs. The story is lucidly told in an article in the Investors’ Chronicle 15 -21 September Cost hikes make life tough for wind developers written by Ali Al Enazi.

How CfDs work

A genuine cost to decarbonisation and investors preparing to profit from it

The Investors’ Chronicle’s weekly columns offer interesting examples of the costs involved in the ‘exciting new green technologies’ from the perspective of investors and rentiers looking forward to benefiting from the green transition. The mining company that will benefit from the inevitable demand for copper for expanded electrify grids, the heating and boiler company in the small shares listed sector that will benefit from the scale of new boiler fitting, the multi utility companies that will power ahead as electrify networks are expanded and the high yield infrastructure investment trusts focusing on wind and solar. This is not to in any way criticise the firms identified by the IC’s journalists, but to illustrate the costs that someone else will have to pay for the green transition be it a private company, household consumers, motorists, travellers or taxpayers.

The Green Growth Tooth Fairy

Politicians, campaigners and lobbyists have spoken about the excitement of green economic growth, oblivious to its obvious yet necessary cost. Esther Duflo, a French economist working at MIT on economic development was awarded the Nobel Prize for economics in October 2019. In an interview in New Statesman with George Eaton the following month she was appropriately sceptical about the possibility of green growth “We need to be ready for the possibility that investments are less productive than we think. The solution then becomes not just electric cars but not driving a car at all.” The obvious comparison that comes to mind is the oil price shock of the 1970s that permanently raised production costs in advanced industrial economies and reduced economic growth.

Need to be open minded and to avoid facile green taxonomies

Four criteria should be applied to assessing green policy: science, technology, economics and finance. We must all try and set aside prejudice. Many people have a prejudice against nuclear – not least people who remember the wilful misleading of ministers in Labour and Conservative governments by the Central Electricity Generating Board about the capital costs and the decommissioning costs of nuclear power. These were only exposed in the preparation for the privatisation of the electricity industry by the Treasury in 1989. We must try to have an open mind about technologies such as carbon capture and clean coal use and the role that nuclear has including that of small modular nuclear generation of electricity. Moreover, facile taxonomies that score one technology as green and other technologies as emitting are a mistake.

The need to interrogate optimistic and precise low costs of green transition

Similarly, precise optimism about the costs of decarbonisation is facile. The House of Lord report draws attention to the Climate Change Committee’s view that extra investment (capital expenditure) to reduce emission will be offset by savings in day-to-day spending operations spending by firms and households. The Lords Committee quotes the Climate Change Committee saying “these savings cancel out the investment costs entirely … which means our central estimate for costs is now below 1 per cent of GDP throughout the next 30 years’.

The Office for Budget Responsibility has come to a similar judgement set out in its Fiscal risks report in 2021: “Our scenario assumes that public spending meets around a quarter of [the cost of delivering net zero]. When combined with savings from more energy-efficient buildings and vehicles, the net cost to the state is £344 billion in real terms.” It said this figure represents an average of 0.4 per cent of GDP a year when spread across three decades. Office for Budget Responsibility, Fiscal risks report, CP 453, (6 July 2021)

The Climate Change Committee said investment will need to increase to around £50 billion annually by 2030. It explained that the largest increases are for low carbon power capacity, retrofit of buildings and the added costs of batteries and infrastructure for electric vehicles. It concluded that the necessary increase in investment “can, and should, be delivered largely by the private sector.” The Climate Change Committee neatly lays out the costs and the savings in precise terms in a chart replicated below taken from the House of Lords Report.

Capital expenditure and operational savings during the transition to net zero by 2050

Renewables and intermittency in the UK context

To accomplish decarbonisation there will have to be a huge expansion of the electricity grid, energy networks, and storage. The extent of intermittency of wind and solar electricity generation over the course of a year in the UK will mean that renewables will have to be supported by other backup technologies. This increases their cost. The scale of the problem of intermittency moreover increases as more renewable sources of energy are added to the electricity grid. In the UK context neither wind nor solar are likely alone to be viable. A suite of other technologies will be necessary. While Analysis from Carbon Brief, an environmental news website, found that costs of renewables have fallen from £167/megawatt hour (MWh) for offshore wind projects coming online in 2017 to £44/MWh for projects in 2023, representing as 74 per cent reduction in price over six years, those figures do not take account of the cost of back up for intermittency. The UK Energy Research Centre’s report in 2020 ‘Integrating renewables into electricity systems’ estimated the cost of integrating and backing up the intermittent renewables to be to cost an extra £10–25/ MWh in ‘systems costs’.

Total power available from wind and solar in Great Britain in 2021

Physical constraints amplified be need for new frameworks of regulation

There are huge practical constraints on the speed of the transition. These include engineering capacity, the costs of the new capital goods that are needed – that will mostly involve the emission of carbon and limited building and construction skills. As important will be the need to radically modify the UK’s distinctive planning system, that delays development when it does not completely block it. In many respects the most challenging matters will be those of economic organisation and regulation to manage a new energy network based on huge upfront capital costs but very low variable production costs at the margin. This will include the physical and economic energy security for corporations and households. Moreover, over the last two years all the principal drivers cost – steel, energy costs and the cost of capital have gone up.

Carbon Price and a Carbon Tax with a Border Adjustment

The key policy necessary for the long and expensive process of decarbonisation will be for the UK government to set a price for carbon and to levy a tax on activities that involve carbon emission. This would cover all consumption and production. To ensure that the carbon tax is not avoided merely using imports it should be buttressed by a carbon border adjustment tax. Sir Dieter Helm set this out for the House of Lords Committee in succinct oral evidence.

In principle, over time, decarbonisation is an expensive but tractable adjustment that will raise the cost of energy use. Fifty years ago, energy use in the UK accounted for around 9 per cent of GDP, today it is about 6 or 7 per cent. The transition will probably involve an increase in cost of around 3 per cent of GDP. This is expensive, necessary, awkward but possible. There is one uncomfortable lingering thought I have. That relates to Professor Duflo’s interview with the New Statesman. Too much green policy is framed around the possibility of carefully calibrated carbon pricing and taxation and the modification of market incentives to remove a malign externality - carbon emission - in some efficient Paretian optimal way. Given the scale of what will be needed to be done a much more uncomfortable and clumsy adjustment may well have to be made using processes of regulation, command and control. As Dieter Helm once put it to me when we gossiped about it a few years ago, you cannot normally fight and win war through Paretian optimal market forces.

Warwick Lightfoot

29 September 2023

Warwick Lightfoot is an economist who served and Special Adviser to the Chancellor of the Exchequer 1989 to 1992