The de facto end of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism

The European Monetary System collapsed thirty years ago in August 1993. This note looks at how it worked, appeared to lower inflation at a price, features of exchange rate targets and the ERM’s end.

On 2 August 1993 when the decision was taken to widen the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) bands from 2 ¼ to 15 per cent, it effectively ended the European Monetary System (EMS). In the present international inflation crisis finance ministries and central banks have been reticent about discussing the role of exchange rates in the international pass through of price pressures. The crisis that led to the end of the European Monetary System 1993, and the subsequent Mexican and Asian currency crises in the 1990s put monetary authorities off explicitly exploring the impact the exchange rate has and policies to manage it.

EMS explored in four parts

This note explores the history and operation of the European Monetary System in four parts. Each section can be read coherently alone.

Part 1: Collapse of the European Monetary System in August 1993

Part 2: Origins and evolution of the European Monetary System (EMS)

Part 3: Postmortem on the collapse of the ERM 1992 to 1993

It does not offer a chronological account of the economic history involved but tries to unpick the analytical features of the EMS’s operation and the institutional and political economy that shaped it. Nor does it explore the wider issues of European economic and monetary union. It examines the pathologies that contributed to EMS’s final period of crisis and collapse between 1992 and 1999. This includes drawing attention to data taken from central banks that exposes the periods of pressure the EMS was under from external events, such the valuation of the dollar and adverse shocks affecting currencies outside the EMS that had chosen to target either the Deutschmark or the ECU. The EMS also illustrates interesting examples of deep institutional behaviour that have a habit of being repeated. These can be seen in the role of agriculture in the EU, the operations of the Bank of England in the London money market and the persistence of international French monetary policy objectives during the EMS. It focuses on the EMS and the artefacts of exchange rate targets and does not attempt to explore European economic and monetary union, the structure of the euro-zone or the conduct of the European Central Bank.

Part 1: Collapse of the European Monetary System in August 1993

What to do about Bretton woods? Farmers and the Snake in the Tunnel

The EMS was set up in March 1979 to revive the European Economic Community’s early steps towards monetary union, to facilitate trade within the Common Market and to address an awkward inconvenience that resulted from the end of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates, to reduce instability in agreed intervention prices within the Common Agricultural Policy. The decision by President Pompidou and his Finance Minister Giscard d'Estaing to devalue the franc by 12.5 per cent in August 1969 created sufficient inconvenience to merit the establishment of the Werner inquiry into economic and monetary union. Collapse of the whole thing invited a response on a different level, the European Snake within a Tunnel.

After that collapsed in the mid-1970s, the European Monetary System launched in 1979 appeared in what appeared to be an ambitious venture. The EMS evolved in several distinct phases. Its character changed. From being a flexible pegged grid of exchange rates that could be realigned to adjust to shocks and changes in competitiveness, it became a de facto fixed parity regime. It could not adjust and eventually broke up.

Currency Realignments in the ERM 1979 to 1993

The Bloody British Problem

This was explored by an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis in a paper The Vulnerability of Pegged Exchange Rates: The British Pound in the ERM by Mathias Zurlinden, an economist with the Swiss National Bank as a visiting scholar at the Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis, published shortly after the EMS collapse in September 1993. A powerful point made in the paper was that there was a doubt about the credibility of the British commitment to its chosen parity against the Deutschmark from the beginning of the entry Sterling into the ERM in 1990.

The EMS had a longer history than British participation in the ERM, and its story is much bigger than the vicissitudes of British monetary policy. Yet Sterling’s presence in what had become a fixed parity regime that was expected to become the glide path to full monetary union, amplified its tensions and contributed to its end.

Technically the ghost of the EMS lives on. Economies such as the UK remained members of the EMS even after they had withdrawn from the ERM. The Exchange Rate Mechanism at its heart is inoperative. It exists in an analogous manner to the way in which some countries such as Germany remained technically on the gold standard in the 1930s and 1940s long after it ceased to play any practical part in their financial transactions. Formally and legally, it remains of interest because countries wishing to join the single currency have to have currencies that are trading within the ERM bands.

Practical economic policy lessons from the EMS

The EMS illustrated three practical economic lessons about ambitious exchange rate targets and management systems. The first is that the more similar the economies involved are structurally the more likely a managed exchange rate parities are likely to work. The second is that countries have to be prepared if necessary to wholly align their monetary conditions and chosen rate of inflation. The third lesson is that fixed or pegged exchange rate parties can come under pressure at any stage as a result of events that are completely external to them. To weather such pressures and strains there needs to be one metropolitan monetary authority involved capable of stabilising the parities and prepared to do so, even if that is inconvenient in relation to its own domestic monetary policy preferences and circumstances. During the international gold standard it was Britain and during the Bretton Woods system it was the United States.

Political lesson of exchange rate targets that fail: worse than toothache

The experience of the EMS also illustrates a political lesson. Exercises in international exchange rate coordination start out in an atmosphere of ambitions, cordiality and good will. When the chosen targets collide with market tension the whole thing becomes a nightmare for the official players involved. Not only does it become a Sisyphean task to hold it all together, but one where co-operation descends into perceptions of ill will, duplicity and betrayal, as the parities involved accuse each other of poor policy judgement and failing in delivering possible and expected assistance.

An aftermath of toxic disagreement raised to a high power lingers in collective political memories. This is not in any way confined to the breakup of the EMS and the Bundesbank’s role in it. Much the same was felt about President Nixon’s role in closing the gold window and ending the Bretton Woods in 1971. When he went to speak at the Oxford Union seven years later in 1978, one Fellow of All Souls College thought the most pertinent question to ask him was having wrecked the international payments system, what did he propose to do about it?

Was it all worthwhile after all?

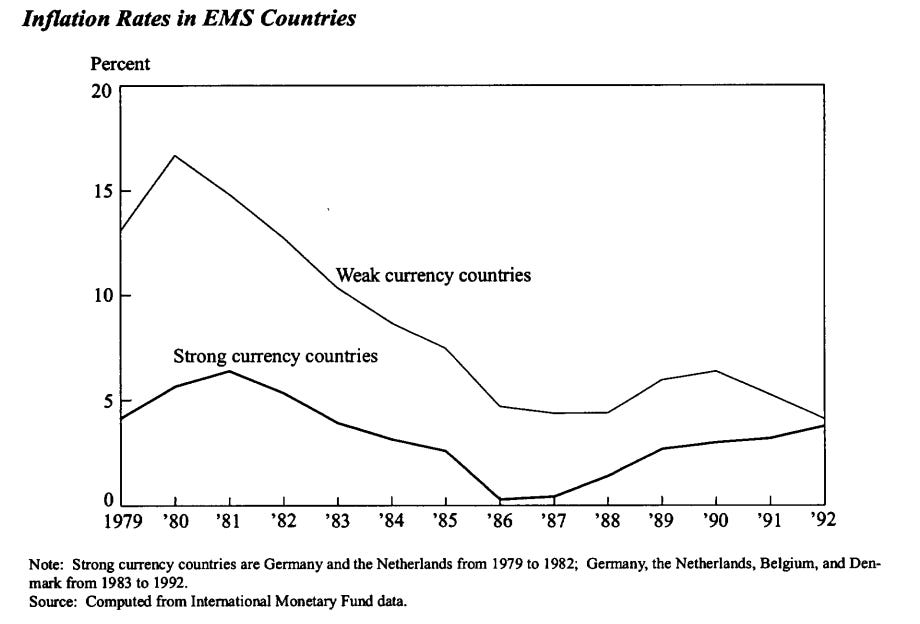

An inevitable question arises: was all the effort with the EMS worthwhile? Most, fair minded economic commentators would accept that the EMS enabled European economies to make significant progress in lowering their inflation by replicating German monetary policy.

Intriguingly that is not the judgement of the German central bank that was the anchor currency at its heart. We know that because the Bundesbank went to great lengths to explain itself on the eve of the creation of the euro in 1999. Fifty Years of the Deutschemark Central Bank and the Currency in Germany since 1948 was published in 1999 edited by the Deutsche Bundesbank. It noted the fall in inflation. Yet it observed that it could have happened through domestic monetary stabilisation and that membership of an exchange rate parity regime increased the economic costs of the monetary disinflation to the countries involved including France.

Part 2: Origins and evolution of the European Monetary System (EMS)

This the second of four notes exploring the history of the EMS. It focuses on its origins, essential features, and broad evolution from a system of regular realignment into a fixed parity grid that appeared increasingly calm until it descended into crisis.

The Snake in the Tunnel

The first practical fruits of the European monetary agenda explored in the Wener Report published in 1970 were the European Snake within the Tunnel alignment of currencies agreed after Bretton Woods was ended at the Smithsonian Conference in 1971. EEC members agreed to maintain bilateral margins between their currencies limited to 1.125 per cent. This implied a maximum change between any two of the currencies of 2.25 per cent, and the EEC currencies moving together and a bloc in relation to the dollar.

The Snake failed. Countries fell aside rapidly. The combination of an international commodity price boom and the quadrupling of oil prices in 1973 was an acutely difficult set of shocks for any fixed parity regime. Yet, even accepting the awkward background it was pretty much bound to fail, because its members wanted to pursue macro-economic and monetary policies that were inconsistent with those of West Germany and the Bundesbank, in particular. Freedom from the inflationary constraints of the Bretton Woods, where Germany had effectively been forced to import American inflation, was going to be used. The Bundesbank was not going to have the same game being replayed but this time with French, Italian and British inflation.

Reviving European Monetary Integration

The idea of another stab at European monetary integration was the initiative of Roy Jenkins, the President of the European Commission in 1978. Lord Jenkins was a highly regarded former British Chancellor of the Exchequer and a gifted political biographer. He had implemented Britain's devaluation against the dollar in 1967, applying the classic principles of a Marshal-Lerner devaluation – stabilisation brought about by the external devaluation being accompanied by a domestic tightening of monetary and fiscal policy. This had been reinforced by IMF conditionality, as part of the agreement for its balance of payments assistance given to the UK. This was the time when, as Harold Lever put it, the Public Sector Borrowing Requirement was turned by the Treasury into a Gatling gun to shoot spending ministers. The principal purposes of the EMS initiative were to revive both the sclerotic pace of European integration and, as Lord Jenkins explained candidly, in his compelling and elegant memoirs A Life at the Centre, to lift Jenkins’s flagging European Commission presidency.

The president of the European Commission Roy Jenkins who revived Europe’s ambitions of monetary integration and proposed the EMS in 1978.

The proposal flew because it attracted the support of President Giscard d’Estaing of France and the West German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt. Giscard d’Estaing had concluded from the Snake that a European exchange rate system, which was necessary for the survival of the EC, would only function if the burden of adjustment was shared equally between strong and weak currencies. Helmut Schmidt’s principal concern was a foreign policy imperative. He needed European and NATO support for Western German security and to safeguard peace. That meant progress on European integration and in the context that ‘essential goal, all the nit-picking about the technical details of monetary union is of secondary importance’ as he later explained to Die Zeit in 1995. In his memoirs Schmidt also explains that he wanted a fixed exchange rate regime for the EC, to create pressure for governments to converge on common monetary and fiscal policies and to create a European currency as a counterweight to the dollar and yen.

President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing of France and the Federal German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt at an EEC Heads of Government and State meeting in the 1970s

Once agreement was reached on the structure of the EMS, its introduction was delayed for almost three months in 1979 by France. This delay arose from an argument surrounding the CAP and French insistence on changes to the agricultural compensation scheme.

President Giscard d’Etaing and Chancellor Schmidt at the1978 European Council in Brussels

The key features of the EMS

The key feature of the system and its formal Exchange Rate Mechanism was that member countries cross-pegged their exchange rates in the framework of the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM). There was a parity grid where there was a commitment to maintain currencies at an agreed rate plus or minus 2 per cent, with plus or minus 6 per cent for Italy. There was a divergence indicator that required a currency that had diverged from its central permitted rate, by 75 per cent, to undertake intramarginal intervention to correct it.

In the event of market pressures or balance of payments difficulty the agreed rates could be adjusted through realignment. From its start there was an asymmetry in its operation. Currencies weakening against their agreed parity were expected to intervene to support it through foreign exchange intervention and through adjustments in domestic monetary conditions. In practice this meant that at some stage most currencies encountered pressure to either tight monetary conditions, intervene to support their currency or devalue against the Deutschmark.

In terms of crisis intervention, the EMS Act of Foundation spoke of foreign support “unlimited in amount.” German Bundesbank officials were anxious that such support would encourage loose monetary conditions in other economies and accommodate inflation. An exchange of letters therefore took place between the German finance minister and Bundesbank President Otmar Emminger agreeing that agreement between the German finance ministry and the Bundesbank that at no stage should any intervention, undertaken to help weaker currencies, compromise the domestic monetary stability of West Germany, the Bundesbank would be able to opt out of it. This became known as the Emminger letter. In September 1979 the German Minister of Finance Hans Mattholfer took advantage of this agreement with the central bank, when he threatened to suspend intervention if exchange rates in the EMS were not realigned.

Dr Otmar Emminger: The President of the Bundesbank whose ‘Emminger letter’ of agreement on the limits of Bundesbank currency intervention with the Federal German Government protected German price stability and eventually sealed the fate of the EMS

In its early years of operation there were frequent realignments within the ERM. Governments did not like tough discipline; they effectively imported the Bundesbank’s preference for price stability and necessary monetary policy to deliver it. They loathed the embarrassment of devaluation. Its bitter pill could be sweetened by a general realignment where their greater devaluation would be matched by a smaller revaluation of the Deutschmark.

Central banks found the burden of asymmetric intervention inconvenient and were not wholly ad idem with their central banking colleagues at the Bundesbank on many technicalities and objectives of policy. This asymmetry at the heart of the EMS, resulted in the rates of inflation of its members progressively converging on those of West Germany. Although their currencies continued to exhibit a risk premium against German bonds – where their interest rates were higher than Germany’s interest rates fell.

The system punished devaluation by requiring countries that had devalued to have higher interest rates even after they had put their domestic monetary houses in order. That was the salutary experience of the Netherlands at the start of the EMS. It coloured the UK approach to membership of the ERM – once in the UK was determined never to devalue. By 1986 the EMS had developed into a Deutschmark- zone. When market forces resulted in a realignment involving a French devaluation in 1987 it provoked much irritation. This resulted in the Basle-Nyborg Agreement where it was suggested that there would be greater reciprocity within the system and coordination between the French and German authorities. It was not clear how this would work in the context of a further crisis given the so-called Emminger letter assuring the Bundesbank that German domestic monetary conditions would not be compromised.

Single European Act, liberalisation of capital controls and what it meant for exchange rates and the stability of the ERM ahead of the Economic and Monetary Union?

The Single European Act agreed in 1986 that established the Single Market for goods, services, people, and capital. This led to an end to capital controls. As a matter of practicality, it was an open question whether an EMS of unadjusted parities could survive fully open capital accounts with no foreign exchange controls during episodes of currency crisis. This concern along with irritations about the way the system operated led to the European Commission President Jacques Delors to chair a committee of central bankers. The Delors Report in 1989 recommended that the European Community should make progress with its long-term objective of monetary union and establish a Single European Currency in a series of stages. The first being membership of the EMS and its ERM narrow bands and the final stage would be membership of the narrow bands with no realignment until ten years later in 1999 they would be permanently locked into the new Single Currency. The merits of the European Monetary Union and the extent to which the euro-zone approximates an optimal currency area are outside the scope of this note looking at the collapse of the EMS.

The EMS’s three distinct phases

1979 to 1983 involved relatively expansionary monetary policies by ERM members relative to those of West Germany. The Bundesbank maintained its non-accommodating monetary policy. This resulted in tensions in the ERM only relieved by parity realignments.

1983 to 1990 participating states pursued stability orientated monetary policies. This was led by France, when President Mitterrand and his finance minister embraced the franc fort policy after March 1983. In this phase inflation and interest rates both converged and fell.

1990 to 1993 the principal background influences were preparation for monetary union following the Delors Report in 1989, the ratification of the Maastricht Treaty and the consequences of German monetary union. EC authorities, the markets and commentators expected the parties based on the last realignment in January 1986 to be the exchange rates of the third phase of the monetary union. The European Commission and the European Council of Finance Ministers tried to make realignment a taboo subject.

Prof Helmut Schlesinger the President of the Bundesbank who thought in September 1992 that the whole parity grid needed a general realignment

In this final phase the EMS was transformed from impressive calm while preparations were made to implement the Delor Report on a single currency, to extreme tension, the Bundesbank President thought it needed a general realignment and invoked the ‘Emminger letter’ to limit is intervention supporting weak currencies, general financial mayhem, collapse, and recrimination.

Part 3: Postmortem on the collapse of the ERM 1992 to 1993

This third note on the EMS looks at the pathologies that contributed to its collapse: the economic and institutional structures necessary to make a fixed parity regime work; the sheer difficult of doing so when extraneous events, having nothing to do with the system itself, such as the strength of the dollar, up-end its cross parities; and the personal recriminations and sense of betrayal that official players perceive when things go wrong and the devastating political consequences of devaluation for the ministers and governments involved.

Everything started to change on 2 June 1992 when Denmark voted no to Maastricht

In 1992 the calm that the ERM had exhibited to the satisfaction of the European Commission and the European Council of Finance Ministers began to change: a weak dollar placed pressure on the ERM parity grid as money moved into the Deutschemark, combined with free movement of capital in 1990, normally there would be a revaluation of the German currency, instead the Bundesbank tried to use domestic interest rates. Market calm was shattered by the Danish rejection of the Maastricht Treaty on 2 June 1992 and the announcement that France would hold a referendum on the Treaty on 20 September 1992. The Maastricht Treaty, formerly the Treaty on the European Union (TEU) introduced the most fundamental and significant changes to EC institutions since the Treaty of Rome in 1957, including the process for economic and monetary union. Its process of ratification in the different member states became progressively more contentious. The Bundesbank was clear that a further realignment of the parity grid was necessary, but that was opposed by the countries that would be invited to devalue. Market sentiment was further unsettled by the increase in the German Discount Rate on 17 July 1992. The stage was set for the collapse.

EMS Decay and the Final Breakdown

The EMS between 1992 and1993 went through a series of exchange rate crises. There were five realignments and two major currencies the Italian Lira and Sterling were suspended from the ERM, and the Spanish peseta was devalued by 5 per cent in September 1992. This was followed by further devaluations of the peseta in November 1992 and the Irish Punt was devalued by 10 per cent on 1 February 1993. A semblance of calm appeared to return to the system and then fluctuations returned, and margins were widened considerably.

On 2 August 1993, even France gave up on the ERM’s narrow bands, after a heroic effort to defend the franc and its so-called ‘franc-fort’ policy. As the Bundesbank noted, the franc was not overvalued after a decade of stability orientated policy. Bundesbank in its book Fifty Years of the Deutschemark Central Bank and the Currency in Germany since 1948, edited by the Deutsche Bundesbank and published in 1999 notes that ‘the events of 1992-93 had a negative political fall out for the Federal Republic of Germany and damaged the reputation of the Bundesbank’.

What transformed this regime of apparent monetary tranquillity and low inflation, that was expected in 1991 to be the glide path to monetary union, into one of extreme financial turbulence, recrimination, and political toxicity?

The limits of Bundesbank reciprocity

The asymmetric commitment of countries with weakening currencies to intervene to protect their value or to accept devaluation offered speculators a one way bet against vulnerable currencies. In a world of hugely increased international liquidity the resources of official institutions could not set foreign exchange rates that were different from market prices for any sustained time. At various stages in the life of the EMS there was an understanding that a currency experiencing difficulty would enjoy some degree of reciprocity from a revaluing currency, in practice that meant the Deutschmark and its central bank the Bundesbank. However, these commitments to reciprocity were always ambiguous and in periods of instability were often found wanting.

Reluctance of countries to agree to a downward currency realignment

A foreign exchange target is very useful given its clarity. If a country can find a stable currency with low inflation that it can target, it can use it to avoid many awkward questions and judgements about its own domestic monetary regime. If its central bank cannot identify appropriate intermediate monetary indicators, such as a reliable framework of monetary targets, because it has an unstable demand for money, or it doubts the efficiency and effectiveness of its domestic monetary authorities, an exchange rate target offers a useful alternative. Part of its attraction is the political pain and the visibility of resiling from it. Countries did not want to be seen to devalue within the ERM as part of a realignment. And they were not enthusiastic about being caught up in a general realignment and then paying an interest rate penalty for their trouble. As the 1980s progressed a stable exchange rate as part of monetary discipline was increasingly perceived as part of good economic governance. The best example of this is the French franc-fort policy embraced by after a succession of downward alignments until 1983. France pursued a policy of strict monetary orthodoxy straight out of the Bundesbank play book, becoming arguably the financially strongest economy in Europe. After the acceptance of the Delors report on monetary union where membership in the narrow bands of the ERM was one of the conditions for membership, reluctance to agree to a downward realignment took on a particular political dimension for countries as part of a wider political priority.

A fixed currency peg requires countries have to be closely economically aligned

Such effectively fixed targets will only work in the long-term if both countries have a shared monetary and inflation objective. Having a foreign exchange rate or external target means that a country surrenders its discretion over its own internal domestic monetary policy. For this to work the economies involved must be structurally aligned with similar agricultural, manufacturing, energy and service sectors exposed to similar shocks and must experience similar economic cycles. They also need to have financial, property and labour markets that adjust to shared monetary instruments in a similar way. If they find themselves in different phases of the economic cycle for a protracted period, it is very difficult to maintain exchange rate parity. There was at least one country in the ERM where these conditions were not remotely met: the UK.

Need for a functioning metropolitan authority to stabilise a fixed parity regime

Historically successful fixed parity regimes have been stabilised by a central metropolitan monetary authority. In the era of the international gold standard that was the Bank of England with help from the Banque de France. During the post-war Bretton Woods era the central was the US Treasury Department and the dollar. When the central metropolitan currency at the centre is destabilised or its authorities are reluctant to act to stabilise the system it falls apart. That was the experience of the international gold standard at the start of the 20th century when Britain was fiscally compromised by the cost of the First World War and Bretton Woods when the costs of Vietnam resulted an awkward the US balance of payments that was difficult to finance, a falling dollar and inflated American prices, in the 1970s.

German Monetary Union in 1990 destabilised Germany’s capacity to be the ERM’s monetary anchor

In 1992 the EMS exhibited every potential radical stress that could destroy any fixed parity regime. Any one of them had the potential to blow it apart. It collapsed as a result, most of them being in play in one form or another. The central problem was Germany. In 1990 German – Federal West Germany and the East German GDR -unification included an economic and monetary union. There was a one for one currency union that presented an immediate inflation problem to the Bundesbank. As well as the immediate inflationary impact of the currency union, the economic union involved huge public expenditure both to modernise East German infrastructure and to raise its residents’ incomes both in terms of public sector and other pay (private sector pay was not fully raised to West German levels) but also transfer payments to West German levels.

This required higher interest rates to control inflation and a surplus on the capital account to finance the imports necessary to bring about German reconstruction. The metropolitan currency at the heart of the stability of the EMS had been destabilised. High short term German interest rates were needed to address inflation. The Bundesbank in the context of a specifically local German domestic inflation problem did not feel able to accommodate the sensibility of the countries even when it was in principle sympathetic.

Fed funds rate and German official discount rate

How helpful was the Bundesbank to currencies in trouble?

In so far as the German monetary authorities could have stabilised the EMS by their actions, they would not do so. Given the reluctance that the Bundesbank had had in assisting other countries when their currencies were under pressure, before the destabilising challenges of German monetary union, the reluctance on the part of Bundesbank officials to help smooth the crises that occurred when Germany had an inflation problem, should not have been a surprise. By 1989 the Bundesbank judged that after a protracted period without any realignments to take account of changes in relative completeness, a general realignment was necessary and certainly necessary ahead of the sort of permanent fixing of parties envisaged by the Delors Report on the creation of the single currency in its final stage.

This meant that when in the summer of 1992 pressures began to emerge the German authorities were not in a frame of mind to accommodate their counterparts with help either in terms of intervention on the scale necessary in terms of foreign exchange intervention, timely changes in German interest rates or the management of market expectations in terms of ‘open mouth operations. At a key stage in Italy’s problems the German finance ministry and the Bundesbank were at one in agreeing that the German central bank would refrain from further intervention to support the lira, invoking the authority of the Emminger letter. This is a good example of where the German authorities having promised supportive intervention, qualified it by ensuring that non sterilised foreign exchange intervention would not be allowed to vitiate domestic German monetary policy.

Italy’s experience in September 1992

The Bundesbank gave the news to Bank of Italy’s Governor Carlo Ciampi in September 1992, who was shocked by the lack of support. The result was that Italy had no choice. On Sunday, evening a 3.5 per cent devaluation of the lira and 3.5 per cent revaluation of other ERM currencies. In effect a cosmetic devaluing the lira by 7 per cent. Other members of the ERM led by the UK, refused to be involved making it impossible to carry out a comprehensive realignment of its parity grid. The Bundesbank did cut the discount rate and the Lombard rate by 50 and 25 basis points respectively. The stabilisation measures were considered inadequate by the markets, given the modest scale of the German interest rate adjustment and no other currencies joined Italy in the realignment.

Sterling, Britain and the Politics of the ERM

The stability of market conditions were further undermined by comments from the President of the Bundesbank Helmut Schlesinger, to journalists at Handelsblatt and the Wall Street Journal. These were reported on 16th September 1992. In them Dr Schlesinger candidly made plain his view that what was needed was a more comprehensive realignment and that without it further exchange market turbulence could not be ruled out. This aggravated doubts among market practitioners that the German monetary authorities would do what was necessary to maintain the existing parities including those of sterling.

There was also a perception abroad that these unhelpful comments had been made with the purpose of being provocative and were a sort of condign punishment for the British Chancellor Norman Lamont. He had at a recent Informal meeting of the Council of Finance Ministers, in Bath in the UK, ‘harangued’ the German authorities demanding a significant cut in German interest rates. This offers an illustration of how politically toxic bilateral relations became among the partner countries involved in the ERM in these crises. After the UK was forced to withdraw from the ERM, the Chairman of the Conservative Party Sir Norman Fowler was asked whether the Chancellor Norman Lamont should resign. Reflecting the political bitterness of the mood, Sir Norman suggested the person who should be resigning was Dr Schlesinger. The irritation and ill feeling generated among senior officials and ministers involved in these crises was vividly explored in a book by a former European Commission official Bernard Connolly, The Rotten Heart of Europe published in 1995. He was an economist who had headed the Commission’s EMS and monetary and foreign exchange unit; his controversial book has an analytical core accompanied by an unflinching exploration of the politics and personalities involved.

July 1993: Finis EMS

The UK and Italy left the ERM in September 1992. Following the French decision in the September 1992 Referendum to ratify the Maastricht Treaty, conditions within the ERM settled. Only to reignite in July 1993 with a full crisis testing the French franc’s narrow band parity. French officials, led by their Finance Minister Edmond Alphandéry, lobbied hard in public and in private meetings with their German opposite numbers, for German cuts to interest rate to take pressure off the franc and avoid the need for higher French interest rates to defend the parity at a time of high French unemployment. There was no adequate German response. On 2 August 1993 France ended its heroic experiment in orthodox monetary policy, abandoning the franc fort policy and with it effectively ending the EMS episode in foreign exchange rate management. As the Bundesbank noted in 1999 after ten years of strict stabilisation measures to control inflation there was no way that the franc could be seen as overvalued.

‘The Bloody British Question’ - Roy Jenkins A life at the centre

The entry of Sterling to the ERM aggravated strains in its operation. Sterling was brought in at a high exchange rate that many economists in the Commission and in European central banks considered to be an overvaluation. This high exchange rate reflected the very tight domestic monetary conditions where interest rates were 15 per cent. These were needed to disinflate the British economy. UK inflation that peaked above 10 per cent was the consequence of domestic monetary conditions that had been too loose that were then amplified by a decision to shadow the Deutschemark informally at 3 Deutschemark to the pound. This resulted in interest rates being cut and increased inflation. In 1990 Her Majesty’s Treasury deliberately chose a high exchange rate to prevent a repeat of this episode. This contributed to the lengthening of a sharp recession. Its trough was in the summer of 1992 (NB on the old non-revised national accounts data). In July 1992 sterling started to fall relative to its target against the Deutschmark. The Treasury took no steps to tighten domestic monetary conditions, given that the last thing the British economy needed at that time was further economic tightening.

While the hands of the monetary authorities were tied, they used every piece of fiscal discretion to stimulate the economy. This was reflected in large discretionary increases in public expenditure in the Autumn Statements in 1990 and 1991 and a large budget deficit. That fiscal loosening was inconsistent with the macro-economic measures needed to maintain an exchange rate target in a fixed parity regime that was under pressure.

Perversely and importantly for overall monetary conditions and inflation, while sterling was weakening against the Deutschmark, it was strengthening against the dollar and on the trade weighted Sterling Index, it was rising. This suggested there was no rationale for either monetary or fiscal tightening given the recession, yet to maintain parity with the Deutschmark domestic monetary conditions would have had to be further tightened. The participation of the UK in the ERM was an example of British policy where neither the ministers nor the officials involved appeared to have a full purchase on the commitments they were making and what would be required to meet them. In many respects the management of sterling’s membership of the ERM was the reverse of the Treasury’s successful management of the 1967 devaluation against the dollar under Roy Jenkins’s political leadership as Chancellor.

Role of external pressures in destabilising the ERM during episodes of crisis

An interesting paper exploring the breakdown of the EMS published by the Banque de France in 2020 and written by Barry Eichengreen and Alain Naef is Imported or Home Grown? The 1992-3 EMS Crisis. It draws attention to the role of external pressures in disturbing the ERM’s cross parity grid. These include changes in the value of the dollar and the challenges affecting currencies outside the formal ERM, but linked to either Deutschmark or ECU (the ECU was the EMS’s synthetic basket of currencies) – such as the Swedish Kroner and the Finnish Marka encountered. Eichengreen and Naef draw on fascinating data from Bank of England sources and information collected by central banks as part of their coordination efforts in sharing data information to illustrate these pressures.

Now we’ve all been screwed by the Cabinet -The Sun 17 September 1992

Their data, for example, show the sheer scale of intervention, not least the £26 billion deployed by the UK in the run up to 16 September when the Chancellor of the Exchequer suspended sterling’s participation in the ERM. This was politically devastating for John Major’s government, given that it represented the complete failure of its central macroeconomic policy membership of the ERM. In political terms it was made worse by its headline visibility. In the same way the devaluation of the pound against the dollar in 1967 was devastating for the Prime Minister Harold Wilson and led swiftly to the resignation of the Chancellor James Callaghan. In political terms an overt headline devaluation, is much more politically painful that a significant downward floating exchange rate.

30-Day moving average of the number of Central Banks intervening per Day

Source: Eichengreen and Naef

Eichengreen and Naef show the sheer scale of the intervention during the various points of the crises. The ‘30-day moving average of the number of central banks intervening. It points to two peak periods: in September 1992 (around the time of the French referendum on the Maastricht Treaty and Black Wednesday, when sterling left the ERM), and in February-March 1993, (which saw pressure on the currencies of Belgium, Denmark, Portugal and Spain) The final crisis of the system, in late-July-early-August 1993 does not show up in this 30-day moving average, since intervention was concentrated in only a few days. That final crisis does show up, however, when we consider the value of intervention’.

Average Deutschmark Intervention by ERM countries, plotted below show ‘the daily average of the value of all Deutschmark interventions. The figure highlights the exceptional magnitude of interventions in 1992-1993 compared to the rest of the sample. The first peak was on September 16, 1992, Black Wednesday, when Britain left the ERM, spending $22 billion, and when the Bank of Italy spent nearly $6 billion in support of the lira. The second peak, as noted, was in July 1993, just prior to when ERM bands were widened in response to pressure on the French franc and other currencies’.

Average Deutschmark Intervention by ERM countries, $ million.

Source: Eichengreen and Naef

In the view of Barry Eichengreen and Alain Naef, ‘economists and historians have paid less attention’ to the external events that the data suggests than they should merit. ‘ERM parities were destabilised by events outside Europe. A limited literature points to the weakness of the U.S. dollar as heightening tensions within the EMS. Dollar weakness was associated with flows from the greenback to the Deutschmark, the closest substitute for the U.S. currency. The Deutschmark therefore rose against other ERM currencies, placing the latter at risk of breaching their bilateral divergence margins. This phenomenon of a weak dollar leading to a strong Deutschmark and intra-ERM tensions was noticed prior to the crisis; it was known as “dollar-Deutschmark polarisation.”

Barry Eichengreen and Alain Naef argue that the’ implication was that the EMS crisis was imported, at least in part, not home grown’….‘As far back as 1979, when the EMS was founded, commentators had observed that dollar depreciation created strains in the Exchange Rate Mechanism, insofar as flows out of the greenback went disproportionately into the Deutschmark, perennially the strong European currency the 1992-3 EMS crisis. We use those intervention data, together with exchange rates and interest rates, to construct a daily measure of exchange market pressure. That series allows us to pinpoint when and where the 1992-3 crisis was most intense. It shows that pressure on EMS currencies started building well before the Danish referendum. It points to a fateful interview by Bundesbank President Schlesinger prior to the September 1992 French referendum on the Maastricht Treaty as the event triggering the most acute phase of the crisis’.

Dollar Deutschmark exchange rate

Source: Eichengreen and Naef

‘Several major episodes of intra-ERM tension and not just that in 1992 are consistent with the hypothesis’. External pressure was a major cause of the ERM’s problems. ‘The dollar had depreciated against the DM in the run-up to the 1987 general realignment, and it depreciated in the period leading up to the 1990 realignment of the lira. They note that foreign exchange market pressure began rising already before the Danish referendum to which much attention is paid in conventional narratives. The dollar had begun depreciating earlier, already in the second half of 1991, and its depreciation continued through the first four months of 1992 (prior to the Danish referendum).’

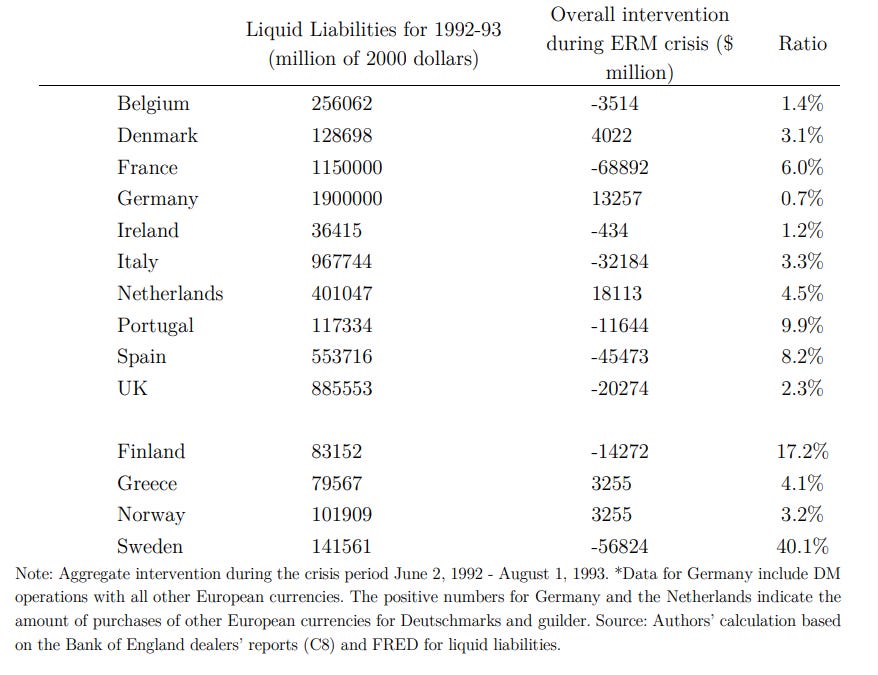

There were ‘large, persistent interventions in 1991-2 by Finland, Sweden and Italy, three of the first countries to feel the crisis. We see an even larger number of substantial, persistent interventions in the second quarter of 1992 when the crisis spreads’. The data shows during the crisis period ‘total net interventions by individual central banks. It highlights the magnitude of Sweden’s interventions, not just relative to the size of its economy and financial system but also absolutely’. In the early 1990s both Finland and Sweden suffered adverse trade shocks affecting their balance of payments because of the collapse of exports to Eastern Europe and the former USSR in particular. Eichengreen and Naef’s data ‘highlights the magnitude of the intervention commitments of France, Italy and Spain. Much has been made of the extent of intervention by the Bank of England in September 1992’. And that data shows that the Bank of England ‘was not alone’ in terms of large-scale intervention and losses’ involving economies outside the EMS. At the time for anyone working in a trading room it was evident that problems showing up in relation to the Kroner or Markka aggravated the pressures on the ERM grid cross parties.

Intervention Net Totals, June 2, 1992 –August 2, 1993 ($ million.)

Source: Eichengreen and Naef

Interventions as share of Gross Liquid Liabilities

Source: Eichengreen and Naef

Conclusion on the EMS Postmortem

Fixed parity exchange rate regimes need coherent monetary and inflation objectives that are shared, economies that are in the event of a market crisis prepared to effectively lock their monetary policies together, and a powerful anchor monetary authority capable and willing to stabilise the agreed rates. Moreover, it will work best when the economies are similar and less exposed to asymmetric risks. Even when all these things are in place wholly external events of the sort explored by Barry Eichengreen and Alain Naef in their paper for the Banque de France can destabilise an otherwise functioning system. When there are tensions and things break down the political price is high, and the recrimination is great.

This invites the question: is it all worth the effort? The great merit of the EMS and its formal exchange rate mechanism is that it enabled countries to target German monetary policy and get inflation down. Yet in the judgement of the Bundesbank inflation would have fallen given appropriate domestic monetary policies. What is more, the Bundesbank concluded that the agreed ERM parties increased the cost of the process of disinflation by removing the exchange rate as an amplifier of monetary policy capable of contributing to shock therapy. We know what the Bundesbank thought because it set out its conclusions in Fifty Years of the Deutschemark Central Bank and the Currency in Germany since 1948 to 1999, in a sort of living will for central bankers.

Part 4: Economic History, the distinctive institutional imperatives illustrated by the vicissitudes of the EMS

This is the fourth note exploring the EMS. It looks at some of the institutional idiosyncrasies that its history and operations illustrate. As well as being an important episode in monetary history and exchange rate management, the evolution and operation of the European Exchange Rate System (EMS) exposes interesting patterns of institutional economic history. These institutional imperatives are consistently underestimated in contemporary economic analysis. There are three that are worth mentioning: they relate to the role of farm policy within the EU; the open market preferences of the Bank of England; the monetary history of France. Identifying the idiosyncrasies that colour institutional behaviour and economic policy is overlooked and is often a rewarding exercise in trying to understand policies and events.

Agriculture and Europe

The Common Agricultural Policy CAP was the first major programme or policy agreed by the original six members of the Common Market in the early 1960s. Agricultural controversies and exigencies have consistently played a significant part in the politics and economic and budget management of the EU. The first practical impulse to explore what monetary union may involve was the commissioning of the Werner Report, published in 1970, reflecting the problems for the CAP arising from French devaluation in the Bretton Woods system against the dollar in 1969. The operational start of the EMS was delayed until the Spring of 1979, because of a row led by France about farm support prices. Much of the EU’s budget problems and institutional development has been constrained by farm policy related questions including the terms on which central and eastern European countries have been admitted.

A good example of the continuing significance of agriculture and the Common Agricultural Policy is the FT Big Read - The ‘monumental consequences’ of Ukraine joining the EU published in the Financial Times on 7 August 2023 that explored the complexities of Ukraine’s desires for membership of the EU. It suggested that it raised profound questions about the EU’s capacities to accept new members and the future of the European project. It notes ‘that Ukraine’s entry would make France a net payer into the CAP, and Poland would swing from the largest net recipient of EU funds to an overall net payer.’ The central role of agriculture and the CAP in the EU is illustrated by the comment made by a diplomat quoted by the Financial Times ‘if you are in an office at the top of the commission, you can either double the EU budget or make everyone swallow sacrifices’.

Redundant institutional relationships linger even the Discount Market

The Bank of England was established in 1694 as a private chartered company which it remained until it was nationalised in 1946. In the 19th century it took on the functions of central bank stabilising money markets and acting as a lender of last resort, in the manner catalogued by Walter Bagehot in his famous book Lombard Street. As a private profit-making bank it did not like giving money to its direct commercial competitors. So, the Bank, the Old Lady as it was known, carried out what would now be called its open market operations through the specialist bill brokers known as the Discount Houses. After nationalisation such considerations were irrelevant yet this operational approach was maintained until the mid-1990s and the introduction of the repo. The Discount Market and the assets of short-term Treasury bills and other commercial bills did not offer a large enough balance sheet for the central bank to manage the London money market from one day to another. There were by the early 1990s repeated shortages that could not be relieved and surpluses that meant that the overnight money rate yo-yoed around above and below the central bank’s policy rate. The Bank, moreover, mediated its open market operations through the discount houses rather than talking directly to the principal players involved the big UK clearing banks and increasingly the American and Japanese banks that were present in the City of London. A clumsy and poorly explained operation to relieve a shortage in the Discount Market in the summer of 1992, was misinterpreted as testing the market for a fall in interest rates rather than a technical manoeuvre to deal with a structural problem in the money market. The foreign exchange markets started to sell sterling and the authorities were never able to quite put that behind them in the difficult month leading up to Sterling’s departure from the EMS. Use of the discount market was not the cause but an aggravating inconvenience. Even after the central bank had fully modernised its open market procedures, it still encountered criticism in terms of its response to liquidity crises that emerged in 2007.

France: long tradition of involvement in and preserving with international monetary coordination

France has a long economic history where, against the odds, it sticks to a form of severe monetary orthodoxy that impedes its real economy and aggravates losses of output and employment. Before the First World War started in 1914, the Banque de France was an active collaborator helping the Bank of England to stabilise the international gold standard. It played a central part in managing a system that lacked liquidity and sufficiently available gold reserves. This was in marked contrast to the Imperial German Reichsbank that usually stood aside when there were tensions in the system.

In the 1930s France was one of the last economies to abandon the international gold standard and only did so as part of a general international realignment in 1936, involving Switzerland. As a result, France endured a much longer slump in output in the 1930s than other countries that abandoned gold earlier such as Britain in 1931 and the US in 1933. In 1958 President De Gaulle appointed, his financial adviser Jacques Rueff, as chair a commission on fiscal and monetary reforms for France. Rueff contributed to the French authorities’ preference to hold large gold reserves even when the dollar had pretty much replaced gold in the Bretton Woods system.

Once Bretton Woods had collapsed France was the country that was persistently most interested in trying to stabilise exchange rates in Europe and to promote wider international exchange rate coordination. As part of this France has astutely worked to get French officials appointed as heads of both the IMF and the ECB. In the evolution of the ERM, it was France after 1983 that embraced financial orthodoxy and the franc fort policy and stuck with it to the bitter end at great cost in terms of output and employment – some of the employment losses were structural and unavoidable given France’s wider social and economic choices, but the franc fort aggravated the structural micro-economic problems France exhibited and made the cost of lowering inflation greater than it would have been with a more flexible exchange rate. Yet it stuck to the narrow ERM parties to the bitter end in August 1993.

Germany’s folk memory of hyperinflation in 1923 and the Bundesbank’s culture of currency stability

Currency stability was central to German reconstruction after the Second World War in 1945. The introduction of the Deutschmark was central to the success of the post-war West German economic miracle that Ludwig Erhard presided over. Price stability and prudent public finances were at its heart, exemplified by the so-called Julius Tower fiscal surpluses of the 1950s. Throughout West Germany's membership of the Bretton Woods system, the flexibilities afforded by the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system in 1971 and the period of the EMS between 1979 and 1993, the Bundesbank consistently gave priority to domestic German monetary stability and low inflation over any international agreements to coordinate policy and target exchange rates. As part of the process of German unification Chancellor Kohl in the 1990s gave priority to Germany’s wider political objectives and agreed to the Deutschmark being subsumed into the Euro in 1999. The interesting question in future decades will be the extent to which German cultural attachment to a strict version of monetary stability endures, as the folk memories of the Weimar inflation a century ago recede, and how Germany would respond if there should ever be a significant tension between a German interpretation of price stability and wider EU monetary policy managed by the ECB.

Warwick Lightfoot

8 August 2023

Warwick Lightfoot is an economist who was Special Adviser to the Chancellor of the Exchequer between 1989 and 1992. He was standing next to John Major when it was announced that Sterling would enter the ERM in 1990 and was Treasury Economist in the foreign exchange and money markets trading room of the Royal Bank of Scotland, as the crises of the EMS unfolded between the summer of 1992 and August 1993.