Rachel Reeves: huge Labour Budget, many measures, big increases in spending, taxation and borrowing. But nothing to show for it, in terms of higher economic growth

The OBR’s economic forecast lowers its forecast for GDP growth, exemplifies crowding out effects arising from higher public spending and no change in the trend rate of growth

The Chancellor of the Exchequer Rachel Reeves has made economic growth the central plank of her economic policy. Labour’s purpose or mission is to increase GDP growth to generate the tax base to pay for improved public services.

The Chancellor has a highly stylised account of how growth can be increased in the British economy. At its heart there is the belief that higher public investment and higher private sector business investment will raise GDP growth.

In working up this proposition the Chancellor’s thinking is firmly located in the mainstream thinking of the contemporary British economic establishment. The central economic purpose was expressed in the Chancellor’s mantra: invest, invest, invest. It invites comparison to the enthusiasm of the National Economic Development Council for investment in the early 1960s and the National Plan published by the Labour Government in 1965 that forecast an increase in output of 25 per cent, not least because of the Chancellor’s own nostalgia. She has expressly invoked the example of Harold Wilson’s Labour Government.

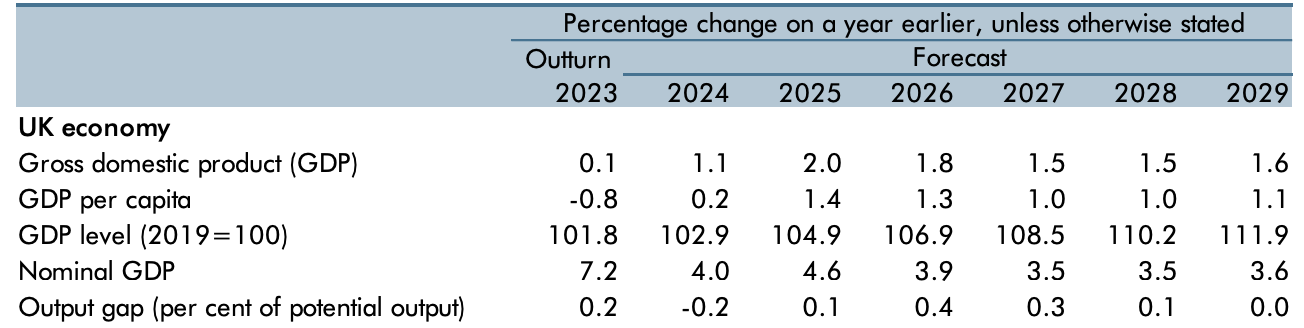

The OBR’s economic forecast from the Government’s perspective is a disappointment. Expected economic growth is lowered. The trend rate of growth is unchanged and the OBR identifies striking examples of crowding out effects arising from higher public seconding that reduce growth after about two years.

This note focuses on the Office for Budget Responsibility's OBR’s economic October 2024 economic forecast that was published with the Budget Redbook. It has figures for the outturn in 2023-24 and forecasts for the period between the financial years 2024-25 and 2029-30.

OBR forecast for the economy

Whether higher spending on investment translates into a faster trend rate of economic growth in the future, will depend on economic return on investment. It is not at all clear that all or indeed most public sector investment in terms of capital spending in health, education or local authorities yields economic returns that raises economic growth. Nor is it clear that increased private sector investment induced by artificial policy, such as generous capital allowances and tax credits for favoured activities, will result in an economic return that raises the trend rate of growth.

A Budget that ignored the role of incentives in the supply performance of the economy

The Chancellor’s budget ignored any cogent analysis of the role of incentives in the supply performance. It neglected the differences between return on capital before and after tax. It neglected the return on human capital, education and training and how marginal tax rates influence incentives to acquire human capital, supply labour, save and invest. The principal tax measure in the Budget is the increase in employer national insurance contributions. The OBR notes that the measure has a ‘persistent negative effect on working incentives and both labour demand and supply, although one that takes some time to materialise as wage and prices adjust’. The Budget neglects the Manhattan Skyline of malign incentives across the income tax regime and with its measures on employer’s payroll tax and capital taxes damages incentives in the economy.

The Budget in the judgement of the OBR ‘against a broadly unchanged economic and fiscal backdrop since March’ ‘delivers a large, sustained increase in spending, taxation and borrowing’. Spending increases by almost £70 billion - a little over 2 per cent of GDP - over the next five years. Two-thirds of the additional spending is on current spending and one third is accounted for by higher capital or investment spending.

Half the increase in spending is financed by increased taxes, principally higher national insurance on employer payrolls, higher capital taxes on assets and higher receipts that arise from stronger tax enforcement by the revenue authorities. These raise around £36 billion, about 1 per cent of GDP. They will take the total tax burden to 38 per cent of GDP, in five years' time. The rest of the higher spending is financed by increased borrowing of £32 billion, about 1 per cent of GDP.

A large discretionary increase in public spending that will have a real resource cost

The key thing is the overall increase in spending during the forecast period. This raises the ratio of public spending with GDP. It will rise from 44.9 per cent in 2023-24 to 45.3 per cent in 2025-26 and then fall back to 44.5 per cent in 2029-30. The policies announced in this Budget raise spending by over 2 percentage points over the next five years.

OBR’s forecast for the principal fiscal aggregates

Total Managed Expenditure will rise from £1,223 billion in 2024- to 25 to £1,510 billion in 2029-30. The ratio of public spending to GDP will settle at 44.5 per cent of GDP. That is about 5 percentage points higher than before the covid public health emergency.

Public Spending as a share of GDP

Higher Government Borrowing

Half the increase in spending is financed by borrowing. Higher borrowing will average £32 billion over the forecast period equivalent to about 1 per cent of GDP. This discretionary increase in borrowing results from deliberate policy choices rather than an involuntary response to an adverse economic shock., such as the banking crisis and the Great Recession between 2007 and 2010 or the covid public health emergency between 2020 and 2021. It is the largest increase in borrowing since 1992.

Size of Fiscal Policy Packages since 2010

Higher public spending and a higher ratio of public spending to GDP that will crowd out private sector economic activity and slow future economic growth

Once government spending is absorbing over a third of any economy’s output, the benefits of extra spending, at the margin compared to its costs, should be interrogated carefully. It is not clear what an optimal ratio of public spending to GDP should be. Yet policy makers should probably aim to keep the ratio to an average of around 35 per cent over the economic cycle. Once public spending reaches around 40 percent of GDP, policyA makers are likely to be disappointed by the results of increased marginal public spending and it will be exhibiting crowding out effects, where spending displaces growth in private sector activity. The present ratio of public spending to GDP is around 10 percentage points higher than the ratio that would probably be optimal at over 45 per cent.

A Chancellor serious about higher growth would reduce public spending as a share of GDP over time not increase it.

The Chancellor has chosen to make £70 billion of discretionary increases in public expenditure. Given that economic growth is her priority, it would have been more appropriate for the Treasury to identify an immediate programme of financial retrenchment. Instead there are spending increases that are front loaded over the planning period presented in the OBR forecast. That is the central feature of the Budget: an already elevated ratio of public spending to GDP is raised further.spending is on average 1.8 per of GDP a year higher than forecast in the March 2024.Budget.

Everything else is of secondary importance. There is a real resource cost to public spending that the Chancellor has increased and set a path for spending that will amplify the crowding out effects that slow future private sector growth.

A higher tax burden and a change in the composition of taxation that will aggravate the deadweight cost of the tax burden

How public expenditure is financed is a secondary matter. The big issue is how much is being spent in the first place. The chosen method and source of tax financing, however, has implications for the overall deadweight cost of the tax burden. In general a broadly neutral expenditure tax such as VAT will involve the least distortion. Capital taxes and taxes on dividends subject to ‘classical’ corporation tax that is unmitigated, amplify the double taxation of savings inherent in an income tax system. Among the taxes with greatest deadweight costs in terms of losses of employment and income are payroll social security taxes such as national insurance. The Budget has increased the employers’ national insurance rate by 1.2 per cent to 15 per cent and reduced the threshold for paying it to £5,000. This will raise £25 billion over five years. Capital taxes have been raised by limiting inheritance tax reliefs on AIM shares, agricultural land and business assets relief such as private companies and applying inheritance tax to final contribution pension funds. Capital taxes are forecast to rise £5.6 billion as a result of the Budget measures. As a share of GDP they will rise from 1.4 per cent to 2.2 per cent. An increase in the share of capital receipts as a ratio of GDP of over 57 per cent.This will amplify the double taxation of savings income and work to lower the incentive to save and accumulate capital.

The OBR identifies no change in trend economic growth over the forecast period

In terms of its cumulative effects, the budget’s extensive range of measures increased spending, taxation and borrowing, the OBR’s economic forecast is interesting. The OBR does not identify a charge in the trend rate of growth that remains in the ORB's estimation at just 1. ⅔ - under 1.7 per cent. There will be an acceleration in GDP growth over the next two years. The fiscal loosening arising from front loaded higher public spending over the forecast period, raises real GDP by 0.6 per cent at its peak in 2025-26, with GDP growth forecast in that year of 2 per cent. This will temporarily raise output above its potential. In response to capacity constraints, the temporary stimulus will fade as monetary policy acts to offset the excess demand resulting from the higher spending. Real GDP growth is forecast to 1.1 per cent in 2024, 2 per cent in 2025, and 1.8 per cent in 2026. It then falls back to 1.5 per cent

The Budget reallocates resources from the private sector to the public sector - household incomes are squeezed to accommodate the public sector

The Budget measure reallocates resources in the economy. Real Government Consumption rises 0.8 per cent between 2023 and 2029. Over the forecast period real private consumption as a share of GDP falls by 0.4 per cent, as a share of GDP. Government Investment is broadly flat. Real household disposable income RHDI per person is forecast to grow by 0.5 per cent a year compared to 1 per cent a year in the decade before 2020. RHDI per person slows sharply in 2026-27 and 2027-28 and is then broadly flat over the forecast. The OBR's explanation for this is five trends: labour share of income falls back from recent rises as firms rebuild squeezed profit margins ; a substantial part of the the Labour Government’s employer NICs increase, announced in the Budget, is passed on in terms of lower real wages; other Budget tax rises; non labour income eases back; and a rising state pension age lowers benefits payments and incomes in older households.

Real Business Investment growth slows crowded out by higher public spending

Real business investment is forecast by the OBR to fall by 0.6 per cent as a share of GDP from 2023 and 2029. This reflects the reversal of what the OBR considers to be temporary factors that raised business investment above its historical share of GDP. The fall in business investment also results from crowding out of private business activity as a result of higher government spending and higher public borrowing. Growth in real business investment will average 0.8 per cent a year between 2025 and 2029.

Corporate profits are expected by the OBR to be lower than projected in its March 2024 Budget forecast.This results from the Budget decision to increase employers national insurance contribution to 15 per cent and lower the threshold for paying the payroll tax. This increase in statutory costs compounds the squeeze on company profit margins coming from higher labour costs.

Inflation and the Price Level are raised by the Budget measures

The Budget measures raise inflation directly and indirectly through a front loaded demand stimulus that arises from a loosening of the fiscal stance and higher public spending, resulting in output above productive capacity over the next two years. Inflation measured by the CPI is increased on the OBR’s estimate by 0.5 per cent to peak at 2.6 per cent in 2025. The GDP deflator rises in line with the CPIand will increase by 1.3 per cent, over the OBR’s forecast period, due to policy measures taken in the Budget. Around 60 per cent of this increase in the price level arises from higher current spending in Government Departments reflecting the rise in public spending. While 40 per cent of it, comes from the impact of the Budget on consumer prices. When compared to its forecast in March 2024 the OBR expects the domestic price level to be 2.6 per cent higher.

Public sector crowding out of private sector economic activity

The OBR argues in its forecast that the economy is operating close to its supply potential, close to the point where it will encounter capacity constraints. The size of the economy changes little, over the ORB's five year forecast horizon. This means that the ‘significant and sustained fiscal expansion of around 1 per cent of GDP per year crowds out some private sector activity. This lowers consumption, net exports and business investment over our five-year forecast. lower business investment reduces the private capital stock, and so potential output.’, is also lowered. The OBR concludes that ‘normally we would expect this effect to gradually begin to disappear towards the end of our five year forecast. But with interest rates higher at our forecast horizon, as a result of the fiscal loosening, we judge that some effect persists.’

Crowding Out and the implausible estimates of long-term benefits of higher public sector investment in relation to future GDP growth

The interesting feature of the OBR’s analysis and economic feature is that it identifies economic crowding out effects that damage the private sector, halfway through the forecast period arising from increased government spending and other policy measures that follow from the higher spending. The striking feature of the analysis is how swiftly the damage that arises from changed incentives and the economic distortions of public spending deadweight costs present themselves in the OBR forecast. These might have been expected to take longer to become apparent. They normally have medium and longer term malign effects. And by their nature lend to be compounding rather than attenuating. It is possible that the OBR forecasting model is identifying swifter malign crowding out effects that results from the fact that the ratio of public spending to GDP is already much higher that the 40 per cent level where in the past economic policy makers in the UK tended to find constraints such as higher borrowing costs and disappointing tax receipts compared to the forecast and the ratio of spending drifting up as growth in economic activity disappoints.

In response to the interest shown by the Government Economic Service, ministers in the previous Conservative Government and the present Chancellor’s attachment to higher investment as a source of faster economic growth, the OBR has estimated the impact increased public investment on GDP growth. The OBR identifies very long time lags before the benefit of higher investment is apparent in GDP. The OBR’s analysis uses a production function that implies that public and private capital ‘are complements to each other’. In the OBR’s analysis this means that business investment rises in response to a larger public sector capital stock. This means that a sustained 0.6 per cent increase in investment as a share of GDP raises output by 0.43 per cent over ten years and by 1.4 per cent over 50 years. It is not clear that private and public sector investment are straight forward complements to each other within the capital stock; and attaching any significance to a precise number such as 0.4 per cent of GDP over ten years or 1.4 per cent of GDP over 50 years is implausible.

Warwick Lightfoot

5 November 2024

Warwick Lightfoot is an economist and was Special Adviser to the Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1989 to 1992