National Accounts, Intellectual Imperialism of Economics and the critique of ‘mathiness’ in economics

GDP, its level and rate of change and growth is the focus of economic success among commentators, politicians and economic practitioners. Huge attention is paid to its measurement and reported rate of change. It is the prism used to refract many wider political and wider social controversies that are remote from it. The concept is in many respects at the heart of the intellectual imperialism economics has exerted over public policy for over fifty years.

The relative success or failure of countries is measured by their growth rates. GDP is the metric against which social phenomena are scored. Complex and controversial programmes for government are explained and excoriated on the estimates of the extent to which they would promote or retard economic growth measured by GDP. To appreciate why this is, it is necessary to understand what GDP and national accounting are and the extraordinary political salience they acquired in the 1950s and 1960s.

1930s Great Depression, the invention of macroeconomics and measuring national income

National accounting and attempts to measure total national output emerged from the social and economic crisis that resulted from the Great Depression 90 years ago. There was a hunger to understand what was happening to 20th century industrial economies. American policy makers were the first to attempt to measure total national income. The US Senate commissioned Simon Kuznets, an economist at the National Bureau of Economic Research to provide a comprehensive survey of the economy published in 1934. This attempted to measure total national income. Economists in other countries such as Sweden and the Netherlands also tried to construct comprehensive taxonomies of economic output.

Simon Kuznets the economist commissioned by the US Congress to measure National Income

The breakthrough however came in Britain. John Maynard Keynes in his General Theory of Employment, Money and Interest published in 1936 constructed a highly abstract account of what we now know to be macroeconomics. It looked at a circular flow of income and aggregate constructs such as employment, income, saving, investment and consumption. At its heart was an observation that there may be circumstances where there is a permanent deficiency of demand in relation to total productive capacity that could result from saving exceeding investment. This abstract analysis invited an empirical examination to investigate consumption, production, income investment and saving. Keynes wanted that analysis but the government and more particularly HM Treasury displayed little interest in it until the start of the second world war.

Lord Keynes CB FBA the Cambridge economist, public intellectual and wartime Treasury Adviser who need quantitative questions to be answered.

Total war meant complete mobilisation of all civilian resources for wartime production. A question was how far domestic consumption could be squeezed without undermining the capacity of the home front to produce war materials for the armed services. A Cambridge economist working in the Cabinet Office was asked to produce a British version of the national accounts framework that Kuznets had started on in the US.

National Accounts and Richard Stone’s Social Accounting Matrix

Sir Richard Stone’s first iteration of a national accounting framework was published as a Government White Paper in 1941. He then developed this framework in research after the war in the 1940s and in the early 1950s. Stone’s national accounting framework was adopted by both the UN and the OECD for measuring output and growth.

What Stone constructed was an interlocking system of balanced national accounts based on the principles of double entry bookkeeping. Each outlay by every economic agent is scored against a matching transaction by an economic agent in another part of the account. The system has an internal coherence and consistency that is carefully maintained not least by guarding against double counting of economic activity. Stone presented national income in the form of a matrix that meant that the different inputs and outputs of his social accounting matrix swiftly yielded a rich picture of the structure and functioning of an economy. In many respects Richard Stone and his collaborators under the aegis of Lord Keynes, who was the senior economic adviser at the Treasury until his death in 1946, took accounting for national income to a level far beyond the pioneering work of Simon Kuznets and his colleagues at US Department of Commerce.

Sir Richard Stone the Director of the Cambridge Department of Applied Economics who pioneered National Accounts

These sophisticated ‘tableaux economiques’ swiftly invited attempts to model economic behaviour. In the UK this resulted in Stone’s book The Measurement of Consumers’ Behaviour in the United Kingdom 1920-38 published in 1954. In America it stimulated both Kuznets and Milton Friedman to construct a consumption function and led to Friedman’s permanent income hypothesis. An important part of this was Kuznets empirical destruction of Lord Keynes’ absolute income hypothesis that as income rises so will saving. Kuznets used long run linear data to show that the savings ratio remained constant despite changes in income.

The Quantification of Economics and the new intellectual imperium

Economics was transformed. Political economy was over. Economic science had begun. As its intellectual confidence grew it acknowledged its debt to mathematical empiricists, such as William Petty, Edmond Halley and Florence Nightingale – she was a statistical fellow of the Royal Society of Statisticians and inventor of the pie chart – as well a chief nurse to the British Empire. Economics became a quantitative science based on data and sophisticated statistical modelling pioneered by the Department of Applied Economics at Cambridge. It was augmented by the application of the Durbin-Watson statistical test to detect the presence of autocorrelation developed by James Durbin and Geoffrey Watson drawing on previous work derived from John von Neumann.

The pioneers of national accounting went on to develop growth models that were later taken up by the World Bank and the national accounts were increasingly used to model and forecast changes in the economy. These became central to the budget statements, growth plans and complex simulations of competing economic policies.

Growth became the loadstar of success and the tractability of social and economic choices

GDP and economic growth became ubiquitous. In the post-war decades industrial economies experienced unexpected prosperity and measurable rapid historical growth. RAB Butler as Chancellor told the Conservative Party Conference that it was within our grasp to double the standard of living within a generation. Harold Macmillan won an unprecedented third general election on the slogan you’ve never had it so good. Harold Wilson promised even more growth by harnessing the white heat of technology and creating a new Department for Economic Affairs and national economic plan.

A more nuanced appreciation of the way that steady recurrent economic growth could change society was explored by Anthony Crosland in the Future of Socialism. Economic growth could finance rising private consumption and a tax base to pay for the public services and transfer payments to create a more egalitarian society without the necessity of putting up the rates of the principal revenue raising taxes - purchase tax and the basic rate of income tax. Growth made everything tractable. Politicians from Crosland to David Cameron recognised that sharing the proceeds of growth was the device that made life easy for them and enabled them to avoid awkward questions about the character of the political choices they were making

The disappointment where the golden age becomes secular stagnation

Growth in GDP, however, began progressively to slow. The 21/2 to 3 1/2 per cent rates and more, that advanced economies exhibited in the golden years of the 1950s and 1960s slowed. Moreover, the increasingly complex models that economists were using generated misleading results. This was partly the inevitable failure at the heart of the epistemology of the statistical relationships that economists specified in their models. Just because some happened before does not mean it will happen again. This is the powerful insight of David Hume and is central to his empiricism. The Durbin-Watson test had not solved the problem of identifying causation. Many of the questions that economists investigated were much more nuanced than the early clumsy questions that Kuznets and Stone worked on.

In addition, economies change. Long runs of data are not consistent in the economic relationships they yield when what is being modelled undergoes huge structural change – de-industrialisation, the huge growth in services, the increasing relative value of brands and intellectual property rights, digital and weightless economy and an economy where capital markets have been transformed by increasing use of debt and the atrophying of publicly traded equity markets. The UN’s guidance on constructing national accounts for market economies also changed in the 1990s, often to reduce the balancing errors that arose from not including certain forms of economic activity that are difficult to measure. These include the illegal service and trades such as prostitution and drugs, the valuation of farmyard animals, short-life assets such as computer software and the direct estimation of the output of public services.

The New European System of Accounts

These conventions were incorporated into Eurostat’s guidance for national accounts working in the EU and adopted by the ONS as part of the New European System of Accounts in 1998. The approach is laid out in Essential SNA – the Basics for a coherent system of national accounts SNA. It provides a ‘broad view of the fundamental requirements that should be envisaged in the strategic development of national accounts. They centre around the main categories that form the skeleton of the system: stakeholders in the economy, the economic activities they perform, and the scope of their actions, the rules applied to evaluating national accounts indicators’. The broad taxonomy used is laid out in a simplified way by the two figures below.

The definitions, classifications and accounting rules in the SNA

Institutional units cross-classified by sector and ownership - Source: System of National Accounts 1993 Training manual, SADC, 1999

National accounts have increasingly become an abstract construct applying a numeraire that appears remoter from what is being measured

The contemporary guidance on constructing national accounts results in practice a significantly different social accounting framework from that developed by Sir Richard Stone. Moreover, it creates accounts that have less relationship to previous measurements of output and require huge amounts of adjustment to previously published data to get a consistent time series. The result is that the economy recorded in data held by organisations such as the ONS, the OBR and Bank of England bears little correspondence to the economic cycles that policy makers had to manage thirty and fifty years ago. Turning points in economic activity and whole episodes of deep recession have been smoothed away.

The most sophisticated macroeconomic models managed by central banks and international organisations, such as the OECD and IMF over the last thirty years have failed to capture disinflation turning into genuine price stability bordering on deflation, the collapse of interest rates, the collapse of productivity growth, the challenge of creating monetary unions such as the euro-zone, the huge potential for instability in financial markets that led to the crisis between 2007 and 2009 or the recent revival of double digit inflation and the de-anchoring of inflationary expectations after 2020.

As growth rates fell economists realised that their growth models were defective. In the late 1980s and 1990s some of the finest minds in economics turned to growth again and constructed new growth theories. This work generated interesting and often-unexpected results such as constant or even increasing returns to scale from certain forms of manufacturing investment by interrogating huge amounts of international data. Unfortunately, such work was vitiated by wholly defective data from a small number of outlier countries where statistics were inaccurate.

What’s gone wrong in macroeconomics – ‘mathiness’?

It is not a surprise that one of the leading new growth economists, Paul Romer as chief economist of the World Bank, in 2016 gave a lecture at New York University, The Trouble with Macroeconomics spelling out what had gone wrong with quantitative economics. The previous year at the American Economic Association he coined the term ‘mathiness’ to specify the misuse of mathematics in economics. Overly complicated opaque mathematics is used to explore models of economic behaviour that bore no relation to the empirical economy. Moreover, such modelling was often undertaken to pursue a political or policy agenda but dressed up in technical clothes making its practical interrogation all but impossible save for its creator.

Too much importance has been given to GDP, its components and their manipulation. In popular discussion and benchmarking the fact that it is a flow of economic welfare rather than a stock of wealth or capital is often lost in analysis and assertion. The challenges of measuring a changing economy with a fundamentally changed accounting numeraire, national and international comparison based on different and often wholly defective data are enough of a caution even without the fundamental empirical problem identified by Hume in the 18th century that just because something happened yesterday does not mean it will happen tomorrow.

The limits to the information about economic welfare available from national accounts and GDP

These observations about the reliability of and practicality of using national accounts in their own terms has carefully avoided the other obvious limits of national accounts. Right at the start when Kuznets made his landmark contribution to measuring American national income, he pointed out that it did not properly capture economic and social welfare. For example, GDP only scores recorded monetary transactions. Output in a home that is not marketed is not measured.

The tools of economics can only take things so far, other sensibilities require other approaches

Dissenters began to challenge both GDP and economic growth. E J Mishan in the 1960s in The Costs of Economic Growth explored the malign externalities and inconveniences growth could generate in a short book that much irritated his professional colleagues. Fred Hirsh in the Social Limits of Growth explored how difficult it is to generate positional goods that are much sought after simply because another person cannot enjoy them and how services that may be provided within a family on a gift basis may be damaged when commercialised, such as social care. Probably the most vivid attack and the one that got the greatest traction with the wider public was the former Chief Economic Adviser to the National Coal Board, F E Schumacher’s book Small is Beautiful published in 1973. It argued not only that large scale technology may not be optimal but for an alternative economics based on sustainability and human dignity. Schumacher’s critique of modern capitalism took matters into realms that go beyond the tools of economists.

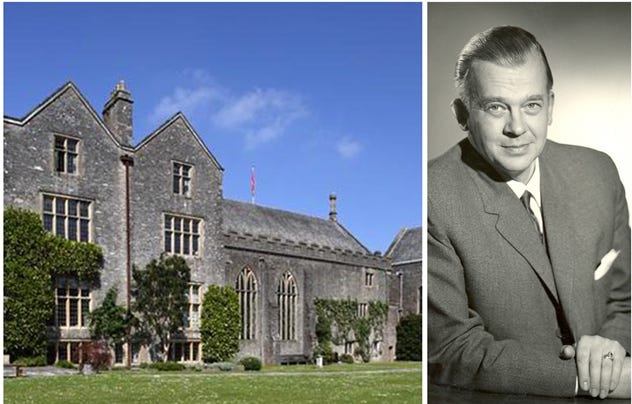

A dissenting perspective at Dartington Hall from F E Schumacher

The Times Literary Supplement rated the book as among the 100 most influential published in the second half of the 20th century. Its legacy speaks directly to the sensibilities of community alienation and challenges of decarbonisation and the management of climate change. The sort of matters that are explored by the Schumacher College at Dartington Hall in Devon in the UK.

National Accounts remain useful in exploring large questions, such as how much an economy is capable of producing, what is its total income, where is that income generated, from domestic local production or from foreign assets that its economic agents own, as rentiers. It is an essential analytical framework, for example, for assessing the capacity of an economy such as that of the Russian Federation to wage war or the long-term geopolitical strength of China in comparison to the USA. Yet in terms of exploring more nuanced questions about economic and social welfare and distribution, national accounts are limited and clumsy.

Warwick Lightfoot

Warwick Lightfoot is an economist who was Special Adviser to the Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1989 to 1992.

12 August 2023