Modern India: A Great Power, a rapidly expanding economy that hosts the world’s third largest equity market

Sovereign Socialist Republic of India, more powerful than the Mughal Empire possessing an economy with dynamism to match.

Modern India is an emerging economy that has the potential to be the world’s third largest economy, as it moves towards its economic development goals. These are to achieve the status of being an advanced economy by 2047 the centenary anniversary of India’s independence from Britain.

India’s place as a great power in terms of any realpolitik assessment of its geopolitical status is for all practical purposes, assured. The combination of its population, the scale of its geographical landmass, the scale of its economy, India's engineering, technology and IT sectors and the size of India’s armed services, along with India’s status as a nuclear armed power, all confirm India’s great power status.

An Indian Army Cantonment near Changdigarph

India’s size, geopolitical importance and expanding economy growing financial market warrant the attention of investors and markets.

This article is based on my observations from a month-long visit to India. As a visitor to India I sought to explore several curiosities. They included trying to acquire a sense of India’s long 7,000 year history, the flow of incursions that have shaped India’s religious and political history, including the legacies that flow from the British incursion that ended in 1947, and the politics, social and economic choices that are shaping contemporary India. Some of this curiosity was embedded in me from my time at school. What were the Morley-Minto reforms, how did they relate to the Montagu-Chelmsford agenda, the Simon Commission and the Government of India Act 1935. Some of this curiosity was stimulated by friends, such as the late Maurice Zinkin who passed the last Indian Civil Service exam in 1938 and served in the Government of India until 1947 and continued to work in India for Uinlever until the mid-1950s. I wanted to see the buildings of New Delhi. I simply wanted to see for myself the extraorinary imperial architectural project that gave the modern Indian Union, Viceregal Lodge that is now the presidential estate, the first parliament building that has now been replaced, the Government Secretariat that is about to be supplemented by a contemporary office complex and the residential quarter of official bungalows allocated to ministers and civil servants.

Part of my curiosity to visit India has stemmed from wanting to understand the cultural legacy that has informed the magnificent achievements of the International Indian diaspora. For me these are exemplified by Jagdish Bhagwati the great trade economist, at Columbia University and Rishi Sunak who enjoyed a meteoric rise in British politics after his election to the House of Commons in 2015. He served successively as Chief Secretary to the Treasury, Chancellor of the Exchequer and as the UK’s Prime Minister. Although his political career may tell us more about the specific circumstances of the culture of elite politics in modern Britain - school at Winchester, university at Oxford, an MBA at Stanford and work at Goldman Sachs than it informs us about India’s contemporary culture. There is certainly interest in India, about Rishi Sunak and his recent private visit to India.

I traveled to India as much interested in contemporary Indian politics and society as in its history, if not more so. I should mention that having visited the Lutyens and Baker architectural legacy and the residential bungalows built in New Delhi, I understand why the Indian Government is likely to want to move on, for completely practical reasons. Inevitably the imperial architectural legacy is of more interest to British visitors with an interest in history than to contemporary Indians that have the inconvenience of living and working in them today.

The British imperial legacy is rapidly receding from popular Indian memory

The British imperial legacy is rapidly receding out of contemporary Indian sensibility. It has been more than three generations since the passing of the Government of India Act 1947. Modern Indians think little of what the Earl of Minto, the Earl of Reading, Lord Irwin or Lord Mountbatten did nor did not do; any more than contemporary people in Britain occupy themselves with thinking about the activities of Herbert Asquith, Stanley Baldwin and Clement Attlee and Sir Stafford Cripps. There are still lingering artefacts of the imperial legacy - the use of the sobriquets such as Town Hall in Amritsar and “Junction’ by Indian Railways to denote a railway station, such as Dufferin Junction as the train from Amritsar approaches Delhi.

Viceregal Lodge Simla now used principally as a postgraduate study centre, but still part of the Indian Presidents’ presidential estate

In Amritsar there are two potent monuments to the British Raj. One speaks to the cruel manner that it was on occasions administered and the other to the social and communal chaos that accompanied its end. The site of Brigadier Dyer’s shooting of an unarmed crowd in 1919, is commemorated with a museum and landscaped garden in the former private enclosed courtyard that would have been dust and perhaps gravel, at the time when the shooting took place. The other is the Museum of Partition that occupies the old Town Hall in Amritsar.

The Museum of Partition is good. It provides a compelling account of the political transactions between the Secretaries of State for India, successive Viceregal governments and the various conferences culminating in the Simla Conference in 1947 at Viceregal Lodge between Pandit Nehru, Ali Jinnah and Lord Mountbatten. And the communal disaster that flowed from its decisions. There were few visitors to the Museum of Partition. It was a quiet refuge of interesting pedagogic contemplation for overwhelmingly occidental tourists, The memorial garden in contrast was a popular and busy site. It was full of vibrant young people celebrating contemporary life. In short it was selfies all round without a care in the world, a celebration more informed by Bollywood, fun and modern IT than any contemplation of India’s history. As several people explained to me, most modern people really do not give Indian history and certainly not the legacy of the Raj, any great thought. The Caravan has moved on.

A Hindu cultural, religious and political awakening

Culturally there is a strong Hindu nationalist awakening that is embodied in the Prime Minister Narendra Modi. With his BJP party he has astutely drawn on popular Hindu sensibilities to buttress his party’s long commitment to market modernisation, structural reform and economic development. Modi’s platform is a combination of realistic economic management and reform, an assertive and confident sense of authority and purpose that articulates the ambitions of the majority Hindu community. It is a mix of a strong state with an increasingly freer and liberal economy, directed and producing results.

The BJP has increasingly combined structural economic change, with a distinct Hindu nationalist reflex that is the antithesis of the Congress Party’s version of secular unity and inclusion. This reflex presents itself in several dimensions. BJP ministers led by the Prime Minister publicly display their own expression of Hindu religious piety and observation of ritual, such as the Prime Minister’s recent ‘dip’ where he performed rituals in sacred waters as part of this year’s Maha Kumbh Mela festival. It involves the authorities sanctioning the recovery of Hindu places of worship from other faiths such as Islam that took them from Hindus at the time of the Mughal incursion.

An important feature of this Hindu nationalism in the northern Indian states, is the active promotion of Hindi and as the national lingua franca, as well as the teaching of classical Sanskrit and enthusiastic attempts to revive it as a spoken language. While removing the teaching of Urdu from the modern languages available as an option on school curricula. The agenda of the central Union Government to promote Hindi as a national language, is controversial and remains highly contested by the southern states. One notable opponent of it is the Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu M. K Stalin.

English fades as India’s lingua franca although a distinct elite English language press continues to flourish

These controversies are long standing and were at the heart of the Commission on languages set up by the Union Government in the 1950s. Whatever controversy there may be over the promotion of Hindi and Sanskrit in relation to other languages and dialects, English appears to be atrophying as the lingua franca in India.There remains a vibrant English language press. The Times of India, The Hindustan Times, The Tribune and the Economic Times are all lively, serious broad sheets of the traditional sort that used to be available in the UK. They provide good coverage of Indian politics, international affairs and what is going on across India. Despite the continuing existence of a lively English language press that continues to attract an elite readership that makes it viable, it appeared to me that the use of English in India was fading.

India’s majority Hindu community has a visceral fear of Islam

Hindu nationalism reflects something greater than a majority culture taking the opportunity to politically assert itself, after a long period where it perceived that its interests and importance were overlooked. There is a visceral Hindu neurosis about Islam. Put simply, there is a fear that differential rates of contemporary fertility between Muslim households and Hindu households will lead over time to the emergence of a Musim electoral majority. This neurosis feeds a Hindu anxiety that as the Muslim community approaches parity with the present Hindu majority, Islam will attempt to expedite the emergence of a Mulsim majority with various forms of communal intimidation such as forced conversion. Among Hindu concerns is a complaint that conventional social security transfer payments and tax relief to assist families with children disproportionately help Muslim families with the financial burden falling on Hindu taxpayers. While this anxiety appears to be genuinely present among Hindus whether it is well founded or not is another matter. It is not clear how the limited framework of social security transfer payments could significantly influence the fertility of any community in India.

The long shadow of the Mughal Empire’s Islamic legacy in India

Jama Masjid Mosque at Fatehphur Siki

This Hindu anxiety about the potential emergence of a Muslim majority was best explained to me in summary form by a highly articulate - at least in English - Sikh farmer in the Punjab. In terms of the timing of the potential emergence of an Islamic majority in India he offered an estimate of forty years. As a Sikh, he expressed no sympathy with Hindu communal and demographic anxieties that he explained so cogently. He made one interesting observation that in modern India the Muslim community was economically very important as merchants, as craftsmen in sectors such as textiles and carpets, and as plumbers, builders and people involved in the construction sector. Muslim communities tend to be less well educated and have less human capital than Hindu households and have relatively lower incomes.

While this anxiety appears to be genuinely present among Hindus whether it is well founded or not is another matter. A Pew Centre paper on the Religious Composition of India written by Stephanie Kramer in 2021 reported a slow decline in the proportion of the Indian population that is Hindu since Partition in 1947 and a rise in the proportion of the population that is Musilm. Between 1951 and 2011 the Hindus have fallen from 84.1 to 79.4 per cent. While the proportion of the population that is Muslim has risen from 9.8 to 14.2 per cent. Muslims have a higher rate of fertility than Hindus, although fertility has been falling among all religious communities and has fallen among Muslims at a faster rate from a higher place. The Pew paper projects that the proportion of Muslims in the Indian population will rise to 18 percent by 2050 and the Hindu share of the population will fall to about 77 per cent.

Jama Masjid Mosque in Delhi

India is not just the world’s largest democracy but a vibrant democracy where change takes place

India is certainly a thriving vibrant democracy. There are elections and governments come and go and there are election upsets. India is undergoing a long political transition.Congress remains the Indian Official Opposition and Raul Gandhi fulfils the role of Leader of the Opposition in Parliament. Yet the political party associated with independence and the glamour of the names Gandhi and Nehru appears to be undergoing a long secular decline. The Congress Party’s core values of secularism and socialism appear increasingly redundant to the Indian electorate. There is an interesting discussion taking place about the future viability of Congress as a natural party of government. Indians, for example, who follow political events in Britain inquire about the emergence of Reform and ask whether its emergence and the atrophying of the position of the Labour and Conservative parties is analogous to the secular decline of Congress.

The slow decline of Congress and its visions of a secular and socialist India

BJP ministers and the Prime Minister are highly sensitive to the perception of the role of Congress in the presentation of post-independence Indian history. Pandit Nehru’s home as prime minister, Flagstaff House, which I did not like, was built originally as the official residence of the British Indian Army’s Commander in Chief, became a museum to his memory, after Nehru’s death in 1964. Prime Minister Modi has insisted that it should be complimented by a new Museum of Prime Ministers that recognises that other parties have held office and contributed to India’s history as well. It is a large modern building built in the grounds of Flagstaff House that uses all the techniques of digital presentation to tell the story of India’s prime ministers since independence.

Pandit Nehru and Congress - India’s Past?

India’s Future with a much more assertive Hindu cultural and political sensibility?

The British economic legacy in India

There is a tendentious debate about the British legacy in India among academics and Indian intellectuals, such as the Congress politician Shashi Tharoor. Tharoor refers to it in his book Inglorious Empire: What the British did to India. It is about the extent to which British taxation, excise duties, trade policy and management of the exchange rate may have hindered Indian economic performance when policy did not involve the egregious looting of Indian economic resources and opportunity.

A central proposition in this nationalist argument that Tharoor concisely asserts in his book is that in the early 18th century India accounted for about 24 per cent of world economic output, while in 1947 India accounted for around 4 per cent of world GDP. This is an interesting debate in economic history. Albeit one that is recondite in character. Yet exploring aspects of this debate has a bearing on understanding India’s economic performance since 1947. It was a proposition repeated by the late Monmohan Singh who served as both as finance minister and prime minister - Shashi Tharoor served as a foreign minister in Singh’s government. Singh was a well trained professional economist, who before going into politics had served as Chief Economist and Governor of the Reserve Bank of India and played an important part in India’s structural economic reforms.. So while Tharoor, may in my view be misdirected, he is in good company.

The ratios of world output quoted by protagonists in this national debate are taken from Angus Maddison’s work attempting to measure world economic activity over about two millenia. Maddison’s work is essentially a heroic effort in measuring national income backwards for centuries. It is a fascinating and magnificent effort of scholarship, yet one that yields data that is wholly unreliable for making any strong assertions or using for establishing any reliable statistical inferences about economic behaviour or causation.

The assertion that the growth of the British economy as a ratio of world economic output and the matching fall in the ratio of India’s share of world GDP within Maddison’s accounting framework, were linked or the result of some form of direct causation of exploitation, is mistaken. The change in the relative positions of China, India and the UK between 1820 and 1947 was driven by a transformation of productivity that was principally the result of technological progress in very specific circumstances. A set of processes that have come to be known as the Industrial Revolution. Technological change was augmented by market institutions that permitted property rights, the enforcement of contract and freedom to adjust prices, production and investment that resulted in repeated cycles of rapid capital acquisition. It created a structure of market capitalism that could quickly adjust to change. New techniques of production were facilitated by a process of that ruthlessly rearranged output and enabled further cycles of capital accumulation to take place. Old processes of production based around agriculture and craftsmanship were simply eclipsed by the scale and range of output generated by the application of new technologies that created new capital stocks that constantly changed. Over time there was a diffusion of technology across Europe and North America.

Swift adopters of technical progress and contributors to it were Germany and Switzerland in the second half of the 19th century. In the first half of the 20th century Scandinavian economies, such as Sweden and Japan were outliers in terms of being economically successful. These were countries that did not have colonial empires. While Britain had the world’s largest colonial empire, the industrial revolution was a specific economic event in the metropolitan heart of the empire that had little to do with the empire itself.

France was the other comparable great colonial empire in the 19th and 20th centuries. Yet France’s adaptation to modern industrial capitalism was hesitant and uncertain compared to America, Britain and Germany. Indeed a proper modern industrial economy only really emerged in the 1950s and 1960s when France was painfully dismantling its empire in North Africa and Asia. British India was not responsible for the Industrial Revolution in Britain, its technology nor the process of intensive capital accumulation that it led to. It was beside the point. In the same way that Imperial China in the closing decades of the Qing Dynasty was an irrelevant bystander to it. It is possible that the commercial networks developed as part of the empire, may have diverted cash and capital from Britain and could have contributed to a relatively slowing capital accumulation in Britain’s industrial heartlands at around the turn of the 20th century.

The Tharoor critique is worth exploring in terms of the modern Indian economy because it betrays an analytical framework that is wholly static in character. It reflects a marxian-socialist analytical stasis. It does not take account of the dynamism that market incentives play in rearranging production. These incentives when combined with technical progress will rapidly expand supply and the productive potential of an economy. Likewise when they are blunted by regulation, controls and clumsy planning frameworks they will blunt the evolution of an economy’s supply performance when they do not contract it.

The socialist intellectual cul-de sac where Pandit Nehru parked the Indian economy in 1947

This goes to the heart of the marxist economic analysis, perhaps best described by Ben Fine. Marx produced a triumphant synthesis of 19th century French socialism, German Hegelian philosophy and British classical political economy. The rub is that the British classical economists were not able to resolve the problem of value. This was probably best exemplified in the Diamond-Water Paradox that was not resolved until the marginalist revolution in economics in the 1870s. This analytical change in economic theory resulted in classical economic theory being replaced by neo-classical economics that employed concepts, such as marginal changes in utility, diminishing returns at the margin, marginal substitution effects and prices and value being determined by relative scarcity. Much of Tharoor’s economic thinking is in effect confined to an intellectual cul-des-ac that is shared by much of marxian and socialist economic thinking. For over forty years Indian policy makers led by Nehru parked the Indian economy in the same cul-des-ac.

The truly malign British influence on post-independence Indian economic policy: Pandit Nehru and Fabian socialism refracted through the prism of Soviet planning and a command economy

The most potent malign imperial legacy that Britain left India may have been Pandit Nehru’s education at Harrow School and Trinity College Cambridge and the connections that it gave him to the leading lights of British Fabian socialism. This was aggravated by Nehru’s admiration for the Soviet example of planning in a command economy, set out in five year plans that emphasised the development of heavy industry. Soviet socialist planning was central to the British Fabian mission in the 1940s. Sydney and Beatrice Webb published their book Soviet Communism: A New Civilisation. They were both evangelists and apologists for the Soviet Union. The Webbs’ nephew Sir Stafford Cripps, a close friend of the Nehru family, who played a seminal role in India’s road to independence in the 1940s was also a committed supporter of Soviet planning and controls. Nehru wrote into the Indian constitution in 1950 that India is a ‘sovereign, socialist, secular, democratic republic’.

The post-independence economic policies of Nehru’s Congress Government were socialist planning on the Soviet model, with five year plans, mimicking the USSR’s emphasis on heavy industry, in the same manner that the People's Republic of China replicated Soviet economics in the 1950s. The five year plans were buttressed by an elaborate framework of economic controls that became known as the ‘licence Raj’, a commitment to domestic autarky and a mercantilist approach to the balance of payments that detached India from international markets.

The ultimate symbol of forty years of Hindu growth and Fabian inspired Soviet Planning: The Ambassador - motoring stuck in the 1950s British Motor Corporation’s less than inspiring output - a Morris Oxford motoring for thirty years

The investment in heavy industry set out in the five year plans was channelled through nationalised public enterprises. This agenda of public investment through state owned enterprises was complemented by policies of trade protection to ensure that state run companies would not suffer from competition from more efficient foreign production. While controls on the amount that private sector firms could produce through an extensive regime of licensing was to ensure that private output was not expanded beyond the scope set out by India’s national planners. Public enterprises were managed to conform to political rather commercial imperatives. Instead of generating operating surpluses that provided revenue for the government they needed financial support to continue in operation. In the 1960s and 1970s the scale of these financial losses contributed to fiscal deficits that an accommodating monetary policy translated into inflation.

The combination of public enterprises that operated below capacity and a corrupt licensing regime for private industry, resulted in significant losses of economic welfare. There were bootle necks and shortages. In the 1970s there was an eight year waiting list to buy a motor scooter. The neglect of goods for consumption meant that Indian consumers had to pay high prices for poor quality consumer goods that foreigners would not accept - apart from some consumers in socialist Comecon economies whose trade was aligned with the USSR.

Among the external advisers that visited India in the 1950s was the American economist Milton Friedman. Friedman was critical of India’s socialist planning and emphasis of the artificial support of heavy industry. His central critique was that by directing resources to sectors that required large amounts of capital when India had limited capital resources resulted in a misalignment between capital that was in short supply and labour that was abundant. The result was that government policy hindered the normal use of capital and labour that should be deployed to take advantage of areas where India would have a cost structure that would give it a comparative advantage in sectors such as light industry. Indian’s embedded economic policy would result in an unnecessarily slow rate of growth. This became known as the ‘Hindu Rate of Growth’ that was capped at around 3 per cent per annum. It was disappointing compared to what should have been possible. Indeed it was disappointing compared to other socialist economies in Asia, such as China in the 1950s and 1960s, in the decades before the economic reform programme initiated by Deng Xiaoping in 1978.

The central defects of Indian policy were too much regulation, lack of engagement with international markets and a complex bureaucracy that made the management of a controlled economy an exercise in adjusting treacle. The heart of the problem was the refusal to use markets and prices to allocate resources. This was exemplified by an exchange that took place by Pandit Nehru and one of India’s leading businessmen J R D Tata the Chairman of the Tata conglomerate in the 1950s. When Tata suggested that state owned companies should be profitable, the Prime Minister was direct, in explaining himself and his policy when he said ‘never talk to me about profit, Jeh, it is a dirty word’.

Nimish Adhia in a paper The History of Economic Development in India since Independence concluded that ‘thirty-five years after independence India’s leadership had yet to achieve, to any significant degree , its pledge of lifting living standards’. While economies such as South Korea, Hong Kong,Taiwan and Singapore were growing rich by exporting the kinds of products that India’s politicised planner had neglected.

In the 1990s and 2000s the Congress’s post-independence socialist structure of controls, plans and regulation was dismantled. In this process marginal tax rates were cut and greater use was made of trade and markets. A foreign exchange crisis that was managed with IMF assistance in 1991 resulted in expedited reform. The licence raj was significantly reduced, the economy was exposed to a greater extent to international trade, state enterprises were sold and foreign investment began to be welcomed. These changes amounted to a significant beneficial structural change in the Indian economy and have resulted in a step change in the rate of economic growth that has improved living standards.

Nimish Adhia’s article sets out the scale of what has been achieved by reform science e 1991: ‘The economy responded with a surge in growth, which averaged 6.3 percent annually in the 1990s and the early 2000s, a rate double that of earlier time frames. Shortages disappeared. On the eve of the reforms, the public telecom monopoly had installed five million landlines in the entire country and there was a seven-year waiting list to get a new line. In 2004, private cellular companies were signing up new customers at the rate of five million per month. The number of people who lived below the poverty line decreased between 1993 and 2009 from 50 percent of total population to 34 percent. The exact estimates vary depending on the poverty line used, but even alternative estimates indicate a post-1991 decline of poverty that is more rapid than at any other time since independence’. In short, radical structural reform that introduced functioning market prices and institutions has created the circumstances where the objective of turning India into an advanced economy by the centenary of independence in 2047, is potentially achievable.

India’s collective action problem that blights its public space lowering economic welfare

In making further economic progress and raising economic welfare there is a specific collective action problem that India should consider addressing, which is as much cultural as economic. In common with many developing economies, such as Nigeria and Sri Lanka, India has a collective action problem in terms of managing its public space. Maintaining and building pavements and highways and keeping them clean does not involve huge amounts of capital and can be done in a cost effective manner when labour is plentiful. Yet Indian public space and basic community public services are neglected. As part of the legacy of India’s license raj there remains an extensive structure of regulation that is redundant and should be discarded. Yet India lacks a framework of rules and effective enforcement to ensure appropriate norms of cleanliness and hygiene in public spaces. This is reflected in the visible squalor on payments, along roadsides and railway lines. It is evident even at many of India’s most important heritage sites that are ranked by UNESCO as being of world importance.

Law, property rights and tribunals to arbitrate disputes

Squalor in public spaces is matched by private squalor arising from what is effectively abandoned property and buildings. There are many derelict houses, courtyards and gardens that result from disputes with families over what should be done with property that they own but cannot agree on what to do with. In many instances there is no effective legal framework of property law and tribunals to arbitrate on these disputes. Their defects did not intrude on significantly on the convenience of British interests and were pretty much left alone.While much play is made of the British legacy of law and courts, the British Raj left the regulation of property rights in rural communities to the frameworks of customary law that were traditionally in place, which were plainly defective.

Site of disputed property left as a derelict mess for years in a UNESCO World Heritage Indian Village

This is not a matter of a low economic development or a colonial legacy. Other economies in Asia offer role models on how public space could be much better managed. They include Singapore, Taiwan and the People's Republic of China. Part of the remedy will lie in the development of more effective comprehensive social safety nets.

India’s history of Non-alignment, the Political Economy of Development and the critique of the Global South

Historically India has been part of the non-aligned movement of developing countries leaving the legacies of colonialism. This has played an important part in India’s self image and Indian sensibilities on a range of issues. In many respects it has been the area of geopolitical management that India has made its own. In 1946 in a radio broadcast on behalf of the cabinet of the Interim Government of India, Nehru spoke of keeping ‘away from the power politics of groups, aligned against one another’; at the UN in 1950 India and Yugoslavia refused to take sides in the Korean war; and in 1952 the Indian Ambassador to the UN, V K Menon first used the term ‘non-alignment at the UN.

Jindal Institute Discussion of Professor Adam’s book on the political economy of the polycrisis of the Global South

The Jindal Institute’s Centre for the Global South held an event to mark the publication of a book Polycrisis and Economic Development in the Global South edited by Professor Hallatchet Adam in February that I attended at the Habitat Centre in New Delhi. It was a helpful opportunity to be reminded of quasi-marxian analysis of international economic relationships and the sensibilities that inform it, expressed in a cogent manner. The overarching explanation for most defects in domestic policy in economies that were once part of colonial empires is the legacy of colonialism. This is the explanation offered for failures of collective action, rent seeking behaviour, and failure to construct policy that could represent a step towards greater economic efficiency an paretian optimality. I found Professor Adam’s event very stimulating and she and her colleagues were generous in welcoming me to their discussion. Yet, it expressed a sensibility that appears to me to be increasingly remote from the realism of contemporary Indian economic policy.

Caste, Religiosity and Changing family structures will require the development of more extensive and coherent social safety nets

One of the most striking features of Asian societies for occidental visitors is the phenomenon of religiosity. Religious ritual plays a huge part in people’s lives, whether it is Hindu, Islamic, Bhudist, Shinto or animism married to folk magic traditions pious observation of religious ritual is a central part of life. The cast system appears to continue to flourish even if its edges have been eroded. The personal marriage columns carried in the Sunday edition of The Times of India offers practical testimony for the importance of both Caste and astrology in family formation in India.

At the same time any suggestion of dismissing a person, as a result of some form of class or cast condescension, invites an egregious row in contemporary Indian public life. The President of India, Mrs Droupadi Murmu is a BJP politician and the first person to be appointed to the ceremonial role of head of state, from a tribal community. After the President delivered a speech to Parliament at the time of the Budget in January, Mrs Sonia Gandhi was reported to have suggested that the President appeared tired from her speech and cut a poor thing. This elicited a visceral response from the BJP accusing Mrs Gandhi of being patronising. In the resulting brouhaha the Prime Minister Mr Modi has accused ‘ Congress Royalty’ of not being able to appreciate a speech delivered in Hindi. Mr Modi himself is from a lower caste family.

Family structures in India are changing and social safety nets will be needed as the structure of Indian households changes to something that is closer to a smaller nuclear family. Large intergenerational households based on cousinage and kinship are exhibiting increased strain as individual relatives make different contributions to the welfare of the household based on their earnings in the market and the savings that they put into building a family home. I had several examples of these family arguments drawn to my attention.These increasing differences in contributions to household resources provide scope for much greater family tension. Traditional intergenerational transfer within households and families may no longer in the future be a reliable way of securing the welfare of people in the manner that it once was.

India’s Budget for 2025 the Finance Ministry’s accompanying Economic Survey

By serendipity, I arrived in India the day after the Finance Minister had presented the Union of India Budget and the economist forecast and analysis that accompanies it. The budget and the economic forecast were comprehensively covered in the English language press.

The Budget presented by the Finance Minister Mrs Niramala Sitharaman focused on measures to support inclusive economic growth through tax cuts to support consumption by middle class households. There is a significant overhaul of the personal income tax regime to support demand for consumer goods, real estate and automobiles. There is an emphasis on employment creation with support for labour intensive sectors of the economy such as the production of leather goods, toys and tourism. The role of small firms in job creation is recognised by the rising of turn over rates as thresholds that cap support for them. There is continued investment in publicly financed infrastructure investment. The ratio of spending on capital will be maintained at 3.1 per cent of GDP.

Tax cuts to support consumption and measures to support employment have been framed in macro-economic strategy directed at financial stability and fiscal consolidation. The fiscal deficit, having peaked at 9.2 per cent of GDP in 2021, will fall from 4.8 per cent in 2025 to 4.4 per cent in 2026. The stock of central government debt is projected to fall from 58.1 per cent of GDP in 2024 to 50 per cent of GDP in 2031. The market expectation was that this fiscal consolidation would enable the Reserve Bank of India to loosen monetary conditions and cut interest rates.

The noteworthy feature of this budget statement and its coverage was the realism about the discussion that surrounded it and the various trade-offs that were implied by the decisions presented by Mrs Miramala. The Economic Survey 2024-25 called for further deregulation of business. While the licence raj has been substantially dismantled there is plainly much more that India needs to do in relation to regulation to avoid hindering economic agents in starting , expanding and investing in businesses. The compliance burden needs to be lowered, particularly for small and medium sized enterprises. In terms of enforcement of breaches of regulation the burden of proof should be shifted from guilty until proven innocent to innocent until proven guilty. An important part in the needed change in the culture of regulation will be at not just the federal Union level of government but the twenty-eight states and eight union territories. The Economic Survey called on the states to carry out a cost benefit analysis of their regulations.

The context of Indian economic policy and development

India has grown rapidly since 2000 at around 6 per cent a year. There has been a big change in the structure of the economy. Growth has been driven by an increasingly productive and expanding service sector. The role of agriculture has contracted from 40 percent of output in 1980 to 15 percent of GDP in 2020. The share of services in value added has risen from 30 per cent to over 55 percent in the same period. The role of manufacturing has been constant, accounting for just over about fifth of output.

An IMF paper Advancing India’s Structural Transformation and Catch-up to the Technology Frontier by Cristian Alonso and Margaux MacDonald, published in July 2024 explains India’s growth and productivity challenges. Their advice is that India still has to move across the technology frontier to increase productivity, increase employment in higher value added sectors such as services and increase the productivity and the value added of the workers who are employed while continuing to expand employment for a growing population of working age.

The paper comments that the ‘ manufacturing sector growth has remained sluggish and over half of all workers remain in low productivity jobs in agriculture, construction, and trade. Furthermore, the catch-up of Indian industries to the technological productivity frontier has been uneven. India needs to create productive, well-paying jobs in labor intensive sectors for its growing population. Combined with a shift of workers towards more dynamic sectors, this could accelerate sustainable, inclusive growth and raise wages for India’s workers’. The IMF economists illustrate this by commenting that ‘while agriculture’s share of value added has declined, it has remained the dominant source of employment. The share of workers in the agriculture sector did decline over time but has remained high: over 42 percent of workers are classified as working in agriculture and allied sectors’.

Much of the IMF thinking is taken on board in the Indian Finance Ministry’s Economic Survey. It is an agenda of exposing domestic markets to more foreign competition, inviting more foreign direct investment, reform of regulation and particularly reform of India’s employment protection legislation. As well as developing social safety nets that will enable people to move from agriculture to construction and manufacturing and form rural communities to urban centres.

The IMF’s regular article IV report on Indian is confident that GDP growth will pick up and rise to 6.5 per cent in 2025, The IMF welcomes the Budget’s emphasis on continuing fiscal consolidation and is confident that the Reserve Bank of India’s approach to monetary policy based around flexible inflation targeting will ensure that inflation will come down towards its target. This will allow an easing of monetary conditions in the way that Indian financial market practitioners expect.Inflation will fall to 4.3 per cent. The IMF forecasts that gross capital investment will be 33.5 per cent in 2025-25. This is close to the ratio of investment that economists at the Finance Ministry believe will be necessary if India is to meet its objective of becoming an advanced economy in 2047.

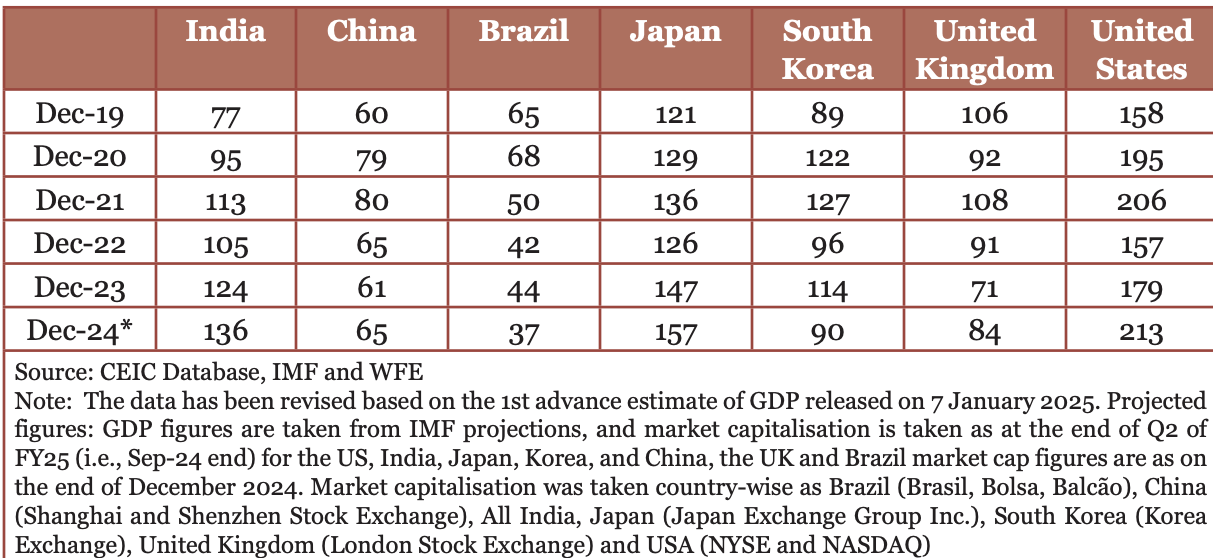

Market capitalisation to nominal GDP ratio (percentage)

A counterpart to this rate of capital formation has been a huge development in India’s publicly traded equity markets. The market capitalisation of Indian equities reached $5 trillion in December 2024. Market capitalisation on India’s stock exchanges has increased rapidly over the last five years from 77 per cent of GDP in 2019 to 136 per cent of GDP in December 2024. The relative scale of this growth in Indian equity markets is reflected in the table above taken from the Economic Survey 2024-25

Warwick Lightfoot

12 March 2025

Warwick Lightfoot is an economist and was Special Adviser to the Chancellor of the Exchequer between 1989 and 1992.