Mathematics and Economics or Black Magic and Alchemy?

Economic data is complex, not reliable for causation. Economists should heed Romer’s Mathiness warnings and Keynes, Friedman on statistical alchemy.

The UK’s official statistical agency the Office for National Statistics (ONS) has had increasing difficulty in producing its normal flow of statistics. Much of this official data is not based on administrative data that can be mechanically enumerated, such as customs data, payments of social security benefits or loans made by banks. Instead much of it is based on surveys.

Problems with the UK Office for National Statistics data

The problem with survey data is that a sample has to be constructed and people have to fill the survey in and do so accurately. The labour market bulletin is principally based on a Labour Force Survey( LFS). For an effective survey that is statistically significant it needs at least 55,0000 individuals to respond and ideally something closer to 60,000. Two years ago response rates fell to 17 per cent. The result was that the LFS lost its formal accreditation as a national statistic. The LFS as a gauge of employment, unemployment and overall labour market tightness, plays an important part in the Bank of England economic analysis that estimates the amount of spare capacity when setting interest rates to meet its 2 per cent inflation target. The Bank of England’s Governor and its Chief Economist have both complained about the deficiencies of the ONS labour market data.

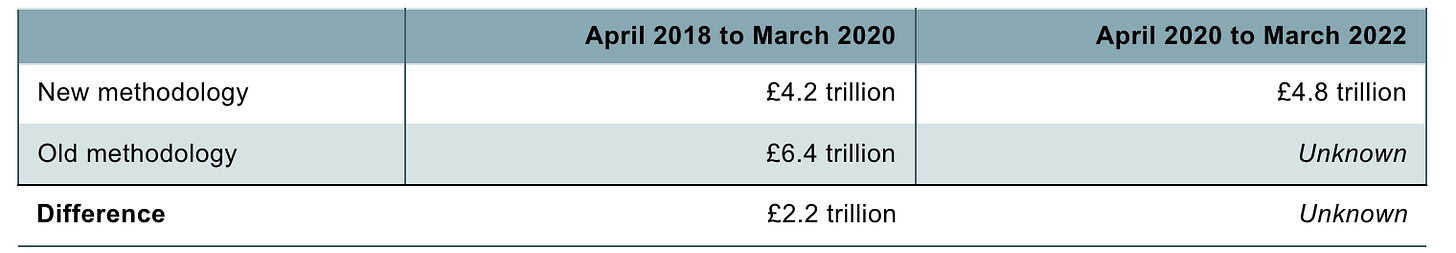

Another set of data that is generated through an ONS survey is the Survey of Household Wealth. The Institute for Fiscal Studies has criticised economic assumptions and judgements made by the ONS in constructing it. ONS has changed the way that it values household wealth held in future pensions. The IFS comments that the ONS has chosen ‘to move away from the use of market interest rates to convert future pension income into today's terms and towards greater use of a measure of forecast GDP growth’. In the IFS’s judgement ‘ faulty’ economics, which results in pension wealth being valued inconsistently with other assets.The change in methodology significantly modifies estimated total household wealth lowering the estimated figure by £2.3 trillion to £4.8 trillion. The important takeaway from this is that the ‘data’ is generated by a survey that is based on complex economic assumptions that raise significant methodological challenges to get right.

Total household private pension wealth in Great Britain according to the Wealth and Assets Survey

Source IFS

£2 trillion than previously thought? Assessing changes to housing wealth statistics

The National Accounts that generate the GDP and Gross Value Added data are similarly significantly reliant on survey data and methodological judgements. Jim Armitage, a Sunday Times journalist, on 25 May 2025, published a wide ranging article cataloging the ONS’s recent challenges in an article entitled What happens when the numbers go wrong. As well as rehearsing the difficulties of the LFS, it drew attention to the ONS decision to revise upwards its figures on the previous two years’ economic growth so dramatically that Britain went from being the worst performing economy in the G7 to being far ahead of Germany and similar to France.’

Probably the ONS set of National Accounts and its various surveys are not much worse than those in other countries and UK statisticians may well be more open about their missteps. What these UK data problems, however, should alert people to is the limitations of data and the sophisticated manipulation of statistical data.There are fundamental problems with the way that economists have chosen to use data that raise fundamental questions of causation, identification and epistemology.

Reliable national accounts data that could be used for asserting processes of stylised causation probably do not exist

Stylised economic relationships and changes in future GDP growth are framed around data that is incomplete and unreliable. Strong propositions, around gravity trade models and returns on public sector infrastructure investment turn on meta studies of international cross country data, often constructed using inconsistent accounting and statistical conventions.

Paul Romer’s critique of Mathiness in Economics

Economists have retreated into econometrics and the construction of mathematical models that are opaque to avoid interrogation of their work and scrutiny of their judgements. Paul Romer, the former Chief Economist of the World Bank, who has made a seminal contribution to modern growth :theory has led an assault on what he calls ‘mathiness’ in economics. He first raised his concern at the annual meeting of the American Association. He wrote up his concerns in the American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings 2015 as Mathiness in the Theory of Economic Growth.

Paul Romer did not pull his punches. He wrote, for example, that ‘ Piketty and Zucman (Capital is Back: Wealth-Income Ratios in Rich Countries 1700–2010.Quarterly Journal of Economics 2014) present their data and empirical analysis with admirable clarity and precision. In choosing to present the theory in less detail, they too may have responded to the expectations in the new equilibrium: empirical work is science; theory is entertainment. presenting a model is like doing a card trick. Everybody knows that there will be some sleight of hand. There is no intent to deceive because no one takes it seriously. Perhaps our norms will soon be like those in professional magic; it will be impolite, perhaps even an ethical breach, to reveal how someone’s trick works’.

Doing card tricks with data, opacity, sleights of hand and avoiding tendentious political arguments from being interrogated

Paul Romer returned to his theme again in September 2016, at New York University’s Stern Business School, in a lecture The Trouble With Macroeconomics. He argued that :

‘For more than three decades, macroeconomics has gone backwards. The treatment of identification now is no more credible than in the early 1970s but escapes challenge because it is so much more opaque. Macroeconomic theorists dismiss mere facts by feigning an obtuse ignorance about such simple assertions as "tight monetary policy can cause a recession." Their models attribute fluctuations in aggregate variables to imaginary causal forces that are not influenced by the action that any person takes.

Economics has an identification problem

A parallel with string theory from physics hints at a general failure mode of science that is triggered when respect for highly regarded leaders evolves into a deference to authority that displaces objective fact from its position as the ultimate determinant of scientific truth.

In the 1960s and early 1970s, many macroeconomists were cavalier about the identification problem. They did not recognize how difficult it is to make reliable inferences about causality from observations on variables that are part of a simultaneous system.Macro models now use incredible identifying assumptions to reach bewildering conclusions’.

Too many modern economists have lost sight of the need for caution about the inappropriate use of mathematics and econometrics. The great historical contributors to the subject in the 20th century maintained an appropriate caution about what Paul Romer calls mathiness. Maynard Keynes and Milton Friedman, for example, were both gifted mathematicians. Keynes had read the Mathematical Tripos at Kings College Cambridge and given serious thought to both probability and index numbers. Friedman at Rutgers University carefully took all the statistical courses expecting to earn his living as an actuary; and when he returned to Chicago University economics department from wartime service at the US Treasury Department was expected given his interests to teach the mathematical economics paper.

Maynard Keynes’s assault on statistical alchemy

Keynes only used statistics to illustrate arguments he was making, as Don Patinkin points out in his article on Keynes in the New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. Keynes did not use statistical analysis as the basis of his conclusions. Despite being a founding member of the Econometric Society and later its president, Keynes was ‘extremely sceptical of econometric methods’.

Keynes wrote that ‘with a free hand to choose coefficients and time lag, one can, with enough industry, always cook a formula to fit moderately well a limited range of past facts. But what does this prove? Is it assumed that the future is a determinant function of past statistics? What place is left for non-numerical factors, such as expectation and the state of confidence relating to the future? What place is allowed for non-numerical factors, such as inventions, politics, labor troubles, wars, earthquakes, financial crises?

Developments in mathematical statistics and the management of linear data, not least those of the British economist Sir Clive Grainger, overcame some of Keynes’s strictures on the problems arising from heterogeneous data; and the Multivariate Granger causality test helped econometricians to establish causation better.

Keynes did think that econometrics could be used helpfully to analyze less complex relationships, such as the demand for new railway rolling stock in relation to the growth in the value of train traffic and the operating costs on British Railways.

Keynes explained in a letter to the Dutch economist Jan Tinbergen, commenting on drafts of Tinbergen’s book on American business cycles - prepared when Tinbergen worked as a consultant for the economic secretariat of the League of Nations, in 1938 - that he did not think it useful to apply such methodology to ‘the general field of the trade cycle’ or the ‘question of what determines the volume of investment’. In a private note to the Cambridge economist and close colleague of his, Lord Kahn, Keynes was more candid. He described Tinbergen’s proof and asked whether his letter to Tinbergen made it clear that ‘it is obvious that I think it all hocus’. Yet Keynes noted that other people were gulled into being ‘greatly impressed, it seems by such a mess of unintelligible figurings’.

Keynes’s review of the Tinbergen’s book appeared in The Economic Journal in September 1939. He described the book as ‘a nightmare to live with and I fancy that other readers will find the same. I have a feeling Professor Tingberen may agree with much of my comment, but his reaction will be to engage another ten computers and drown his sorrows in arithmetic. It is a strange reflection that this book looks likely, as far as 1939 is concerned, to be the principal activity and raison d’etre of the League of Nations’.

Whom Keynes would trust with ‘Black Magic?

Keynes’s review elicited a fourteen page reply from Tinbergen. Keynes reply to Tinbergen was courteous yet intellectually brutal : ‘No one could be more frank, more painstaking, more free from subjective bias or parti pris than Professor Tinbergen. There is no one, therefore, so far as human qualities go, whom it will be safer to trust with black magic. That there is anyone I would trust with it at the present stage or that this brand of statistical alchemy is ripe to become a branch of science, I am not yet persuaded. But Newton, Boyle and Locke all played with alchemy.’

Milton Friedman the Prophet of the Monetarist Counter-Reformation against Keynesianism

Milton Friedman shared Keynes’s reservations about the use of mathematics in economics and the role of econometrics. By chance Friedman also reviewed Tinbergen’s book in the American Economic Review September 1940. He considered Tinbergen’s fifty-equation model as little more than a tautology, arguing the equations in the regression analysis only yielded correlations that were ‘simply tautological reformations of selected data’.

Friedman developed this critique of mathematical modelling in review of Oscar Lange’s book Price Flexibility and Employment. This was in a review of Oscar Lange ‘s book Price Flexibility and employment. Friedman’s complaint is that econometric models provide ‘formal models of imaginary worlds, not generalisations about the real world’. In his view Lange had constructed his arguments and conclusions in a manner that meant that they were not ‘susceptible of empirical contradiction’. Friedman argued that the test of a theory was ‘not conformity to the canons of formal logic but the ability to deduce facts that have not yet been observed, that are capable of being contradicted by observation, and that subsequent observation does not contradict’.

Friedman’s scepticism about the role of maths in economics drew on his wartime work at the Statistical Research Group (SRG). He worked on the testing of new alloy turbine blades in an endeavour to manufacture planes that could fly higher and faster. He used a pioneering large-scale computer built by IBM at Harvard. Harvard’s Mark1 to identify multiple regressions that predict the strength of untested alloys. The equations matched all the data that Friedman had collected to identify what should be alloys of unprecedented strength. When the new alloys were tested in a laboratory at MIT both failed. Friedman found that his calculations could not map what happened in the physical world. For Friedman the challenge of using simultaneous equations to analyse alloys had implications for economists trying to use similar mathematical techniques to construct general equilibrium models. This made Freidman very cautious about readily accepting the predictive power of regression analysis.

Opaque misuse of economics for political agendas

Academic economics has entered a mathematical cul-des-sac where there is much fantasy, remote from the real world as Paul Romer has put it. Ideas are explored in a manner that is opaque and beyond interrogation. These exercises in high powered sophistory have been used to dress up political agendas on distribution, trade, migration and supranational projects, such as the construction of the euro-zone and membership of the European Union that amount to a misuse of economics. Much of the work employs analysis of data that is defective. More fundamentally, it cannot overcome the problem identified by David Hume. Causation cannot simply be established on the basis of assuming that because something happened in the past, it will happen in the future. It therefore would behove contemporary economists to heed the methodological advice of Lord Keynes and Milton Friedman.

Warwick Lightfoot

1 June 2025

Warwick Lightfoot is an economist and served as Special Adviser to the Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1989 to 1992.

Delightful - not just that I agree with you but enjoyable to read. One small bit of duplication:

"Friedman developed this critique of mathematical modelling in review of Oscar Lange’s book Price Flexibility and Employment. This was in a review of Oscar Lange ‘s book Price Flexibility and employment."

Any chance you could identify some of the "supranational" fantasies you refer to, such as on membership of the EU, please ?