Labour’s share of national income rises in the UK, while profitability falls

Unlike other economies wages as a share of GDP have risen in the UK since the mid-1990s, while profits have fallen, reflecting a flexible labour market and limited investment opportunities

Historically factor shares - the income within national income going to labour and capital - were considered to be broadly stable. Over the last thirty years they have plainly not been stable and there appears to have been a shift in favour of capital at the expense of labour. In this secular change in the trend of change in distribution of income between capital and labour, the UK is an outlier. After a dramatic collapse of profits in the 1970s there was a recovery in profits in the 1980s. Yet since the 1990s the share of labour incomes in the UK has risen. In turn profits and the rate of return on capital appears to have fallen. This fall in business and investment profitability has awkward implications for policies directed at raising investment as a share of GDP.

Stable factor shares within GDP for Capital and Labour are a Stylised Fact or maybe not?

Lord Kaldor in a paper Capital Accumulation and Economic Growth published in 1961 observed that factor shares within national income over time were broadly constant. Drawing on data from the US and UK about the ratio of national income recorded as profits and wages, he concluded that while the share of national income received by capital and income over the economic cycle may vary, over longer periods they were broadly stable. He described this as ‘a stylised view od the facts’, and became known as a ‘stylised fact.

Maynard Keynes had noted similarly in 1939 in Relative movements of real wages and output, published in the Economic Journal that the ‘stability of the proportion of the national dividend accruing to labour, irrespective apparently of the level of output as a whole and of the phase of the trade cycle” as being “one of the most surprising, yet best-established, facts in the whole range of economic statistics’.

Over the last twenty-five years this stylised fact constructed by Lord Kaldor has slowly been compromised by evidence across countries that factor shares could change. The evidence was moreover that capital’s share of national income was rising at the expense of labour. This would not have surprised several of Lord Kaldor’s contemporary economists, such as Simon Kuznets, one of the early pioneers of national accounting or Robert Solow, one of the intellectual godfathers of the neo-classical growth model. They disputed that the proposition that constant factor shares was ‘one of the great constants of nature’.There had also been a decisive shift in factor shares favouring labour as a factor of production in the 1970s in the UK, labour, which was then unwound in the 1980s. Yet by 2015 there was accumulating evidence that factor shares are not constant and in many economies were shifting in favour of capital.

Labour’s declining share in the International Economy in the 21st century

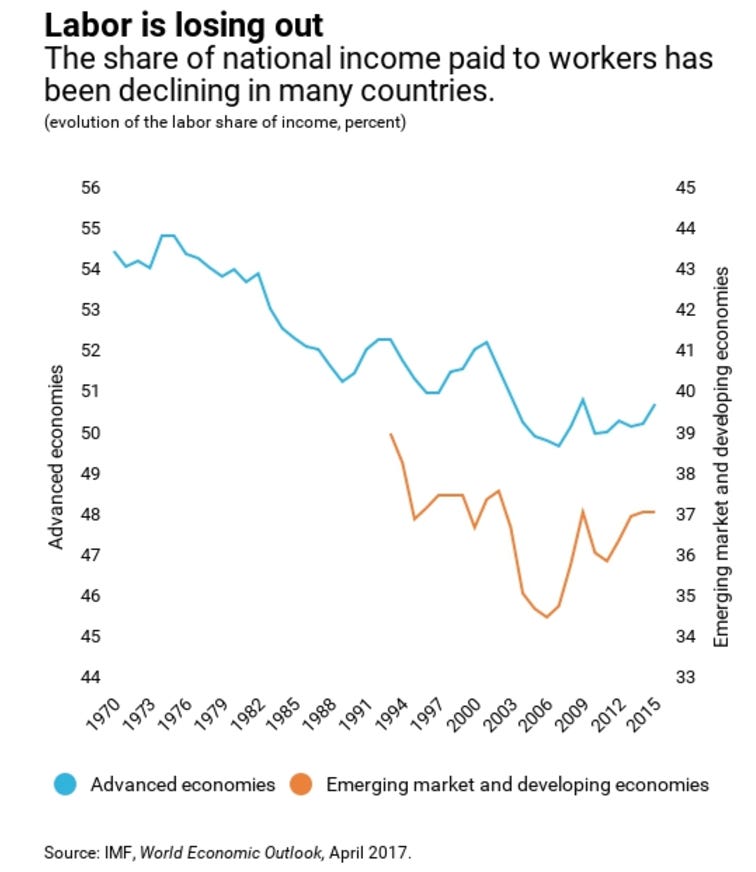

Since 2000 this stable relationship has ceased to be a straightforward ‘stylised fact’. In an IMF Blog Drivers of Declining Labour Share of Income published in April 2017, Mai ChiDao, Mitali Das, Zsoka Koczan and Weicheng Lan point out that ‘after being largely stable in many countries for decades, the share of national income paid to workers has been falling since the 1980’ and drew attention to a chapter in the IMF World Economic Outlook in April 2017, Understanding the Downward Trend in Labor Income Shares. The IMF economists explained that ‘the global labor share of income began a downward trend in the 1980s, declining 5 percentage points to its trough in 2006. It has since then trended up by about 1.3 percentage points, which may reflect either cyclical or structural factors associated with the global financial crisis. This downward trend has overturned one of the enduring stylized facts in Kaldor (1957), which supported a long tradition of assuming a constant labor share of income in growth and other macroeconomic models, and thus raised complex questions about the rising role of capital in production and its implications for the future of employment and labor income’.

The IMF went on to note that ‘the fall in labor shares at the global level is that it reflects declining shares in both advanced and, to a lesser extent, emerging market and developing economies.Indeed, the labor share of income has declined in four of the world’s five largest economies, led by the steepest decline in China’, while the labour share of income in the United Kingdom has trended up’.

There is one outlier where labour’s share went up : the UK

The IMF World Outlook noticed one economy that was an exception to this general trend, the UK ,noting the ‘the labor share of income in the United Kingdom has trended up’.

Estimated Trends in Labor Shares by Country and Sector

Source IMF World Economic Outlook April 2017

Structural change that made markets and the Labour market work better in the 1980s

The distinctive outlier in changed factor shares that favour capital is the UK. This is interesting because there had been pronounced changes in the share of GDP attributed to and capital in the UK economy in the later middle decades of the 20th century - the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. From the late 1960s profits as a share of national income in the UK were acutely squeezed after 1968. The combination of militant trade union pressure on pay, prices and incomes policies that controlled prices, but failed to control pay; and a framework of industrial relations law that had decisively entrenched effective trade union power in the workplace that shifted decisively in favour of trade union militancy as a result of the failure of attempted reform by Labour and Conservative governments - the failure of Labour's In Place of Strife White Paper in 1969 and the Conservatives’s Industrial Relations Act - the collapse of successive incomes policies in the 1970s along with the Trade Union and Labour Relations Act 1976, shifted the balance of power within industrial relations further in favour of trade unions.

The British profits crisis in the 1970s

This shift in dramatic factor shares in the UK was first noticed by Marxist economists. Among the most prominent of them were Oxford economists. Andrew Glyn, the economics don at Corpus Christi College. Glyn and his colleague Bob Sutcliffe, an economics don at Jesus College. In British Capitalism, Workers and the Profit Squeeze, they identified the fall in profits in the UK, as a crisis in capitalism that would undermine the continuing functioning of a market economy in the UK. In the 1970s the UK economy was a ‘mixed economy’ and already partially socialised with a large nationalised sector, many state enterprises operating in the traded goods sector and a large public sector. Andrew Glyn was an attractive and engaging figure, an Etonian aristocrat, the son of Lord Glyn of the Williams and Glyn banking family. He enjoyed provocatively teasing other Oxford economists, such as Walter Eltis that without profits, capitalism could not function. Among the wider community of commentators who picked this up was the Oxford historian, A J P Taylor. In his column in the Sunday Express Taylor made the powerful point that given that capitalism would not work without profits, and no one including the Labour Government at the time planned to replace capitalism in Britain, then they had better set to work to restore profitability swiftly.

In many respects that was what economic policy between 1976 and 1990 was about. The combination of monetary disinflation, the dismantling of price and pay controls, the acceptance that the commitment to full employment set out in the 1944 Employment White Paper could not be maintained through demand management regardless of inflation and wider international competitiveness pressures, reform of trade union law and detailed reform of the micro-economics of the labour market including the abolition of the Dock Labour Scheme, changed the structure of the UK economy. Market discipline was restored. Market prices were applied to more parts of the economy, not least the labour market and labour and product markets were enabled to clear in a manner that had been obstructed by public policy for forty years or more. Trade union reform was central to these changes, but reductions in marginal tax rates lowered the top rate of income tax from 98 per cent to 40 per cent and reduced the standard rate of tax from 34 to 25 per cent played a significant role as well. An important contribution to improving the working of the economy, came from a more neutral tax system that made greater use of expenditure taxation, the reform of capital allowances in the 1984 Budget, as well as the creation of a more neutral tax system, the double taxation of savings income was mitigated by measures, such as the abolition of the investment income surcharge, the development of expenditure tax treatment for Personal Equity Plans and the abolition of Capital Transfer Tax.

The result was that in the UK in the early and mid-1980s the share of profits went up and wages went down. Andrew Glyn who was then the economic adviser to the National Union of Mineworkers, always ebullient, recognised this recovery in profits and expressed concern to Walter Eltis, his opposite number at Exeter College Oxford, that Mrs Thatcher was saving capitalism, by making it profitable again. This was very much a one-off adjustment returning the British economy to profitability. Much of the structural changes made to the British economy in the 1980s returned it to working in the manner that would be expected of a mature advanced market economy. It did not set off a dynamic where capital was progressively rewarded with rising rates of return on capital

In the international economy in the 1990s it became steadily clearer that profitability was rising and the share of national income accounted for by profits, rather than wages, was rising. This secular trend has been undoing Lord Keynes and Lord Kaldor’s constant and stylised fact on stable factor shares.

UK Labour’s share as a factor of production improved as a result of liberalising structural reforms

The fact that the UK is an outlier ,as the IMF World Economic Outlook noted the share of wages in national income went up and profits fell within GDP. Given the radical reform of British trade union law and the scale of the change in the balance of power between unions and employers and the construction of flexible labour market that has demonstrated its capacity to adjust to economic shocks over several economic cycles in three decades, it is noteworthy that the creation of a labour market that clears more easily, has not suppressed the labour’s share of income.

A key part of the explanation has been that employability has increased which has raised employment, participation and lowered unemployment since the 1970s. Strong employment and low unemployment are at the heart of a sustained increase in the share of wages in UK national income. The UK’s experience contradicts the standard critique of so-called neo-liberal structural economic reform. The interesting thing is that this trend has been maintained.

The reciprocal of higher wages - lower profits and the fall in UK profitability

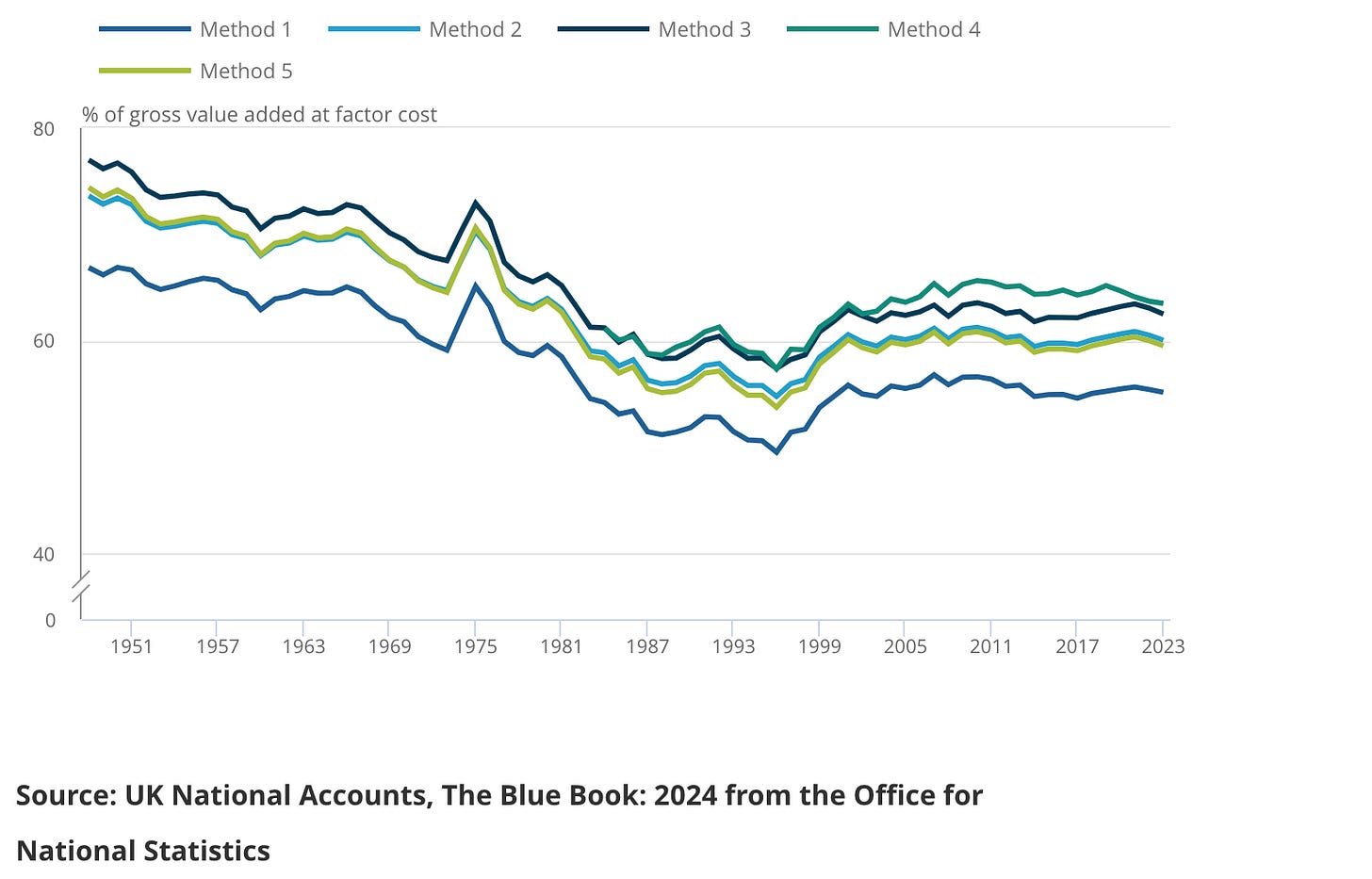

This is clear from the ONS’s latest research note on the subject Trends in the UK labour share: 1997 to 2023 comments that Over the last two-and-a-half decades, the share of total UK income going to workers has increased by just under 6 percentage points; this not only partly reverses the long-run decline in the labour share experienced by most advanced countries, but sets the UK apart as a nation where the labour share has shown a marked increase.

The labour share has increased by between 5 and 6 percentage points since 1996

The different methodologies in the chart refer to different approaches to apportioning income such as the income received by the self-employed and rent from property. These attributions involve complex statistical questions that mainly turn on how to apportion income from self-employment between wages and profits and how things such as rent are apportioned.

The ONS points out that ‘the 5 to 6 percentage point increase in the UK labour share since 1996 was broadly similar across each of the five methods. This partly reverses the long-run downward trend, which has been, and continues to be, a feature of the labour share in most advanced countries. The fact that each of the different methodologies point to an increase in wages as a share of national income suggests that the UK is an outlier contradicting a broader international trend, is not the result of statistical irregularity arising from the treatment of national accounts data.

The ONS note explains this increase in labour’s factor share in the UK to structural changes in the economy. Among them a shift towards services ‘where the labour share tends to be higher, particularly the professional and administrative support, and the government, health and education industries’. Other factors the ONS identifies include ‘rising numbers of graduates who earn a wage premium over non-graduates; and higher pension contributions by employers reflecting auto-enrollment and moves to plug deficits in employer-sponsored schemes’. The National Minimum Wage has also played a role, particularly over the last decade.

In the UK, in the view of the ONS there has not been a decoupling between productivity and pay that has taken place in most advanced economies. As a result the ratio of labour incomes has risen given that real pay has grown more than productivity.

The reciprocal of higher wages - lower profits and the fall in UK profitability

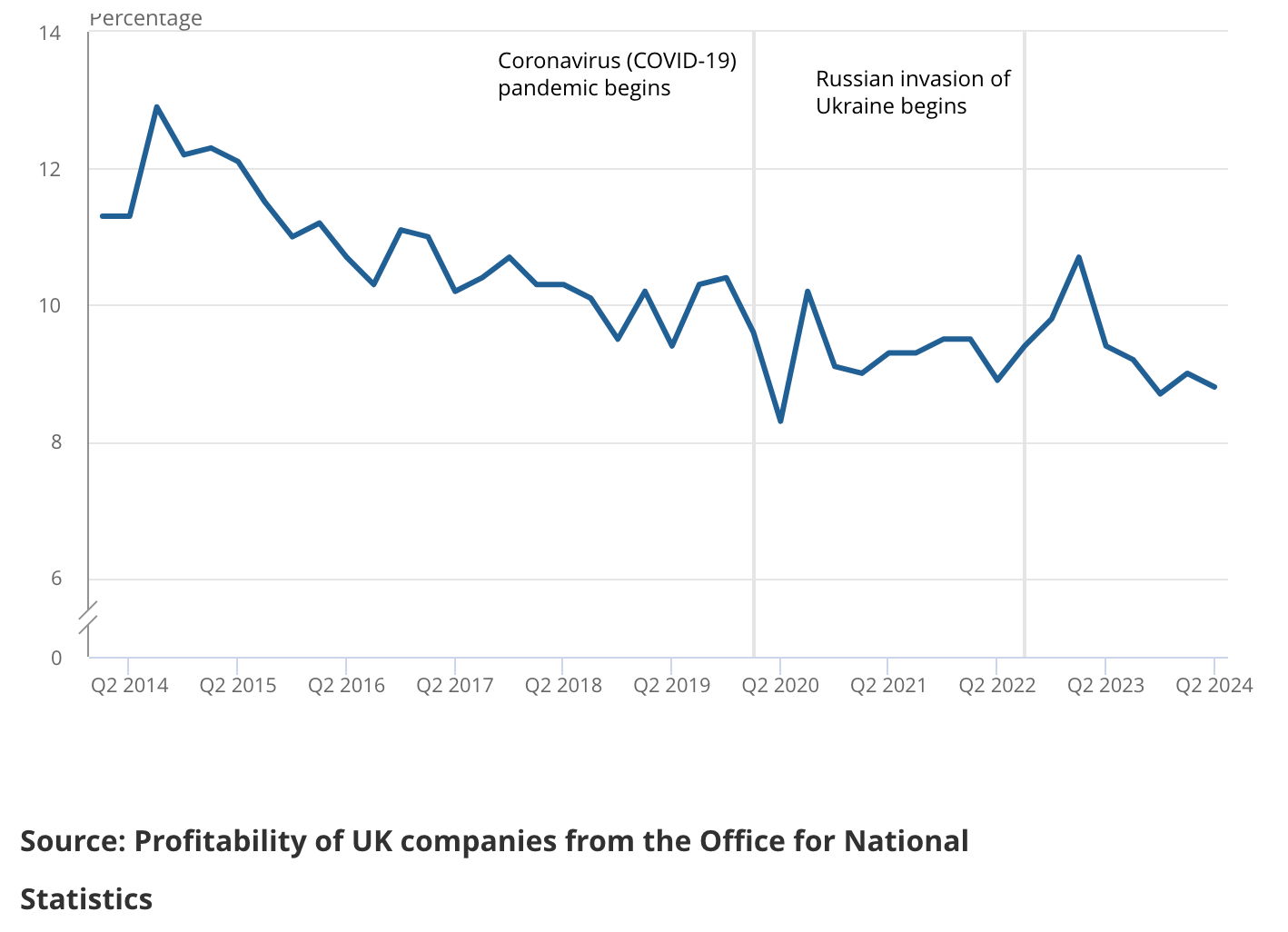

The reciprocal of higher wages - lower profits and the fall in UK profitabilityThe reciprocal of a rise in the ratio of national income accruing to labour as a factor share, is a fall in the ratio of factor income going in profits. Profits within national income get less attention than wages, notwithstanding the late Andrew Glyn’s arresting Marxist analysis in the 1970s and 1980s. The latest ONS bulletin on Profitability of UK companies reports that ‘The net rate of return for private non-financial corporations (PNFCs) was 8.8% in Quarter 2 (Apr to June) 2024, down from the estimate of 9.0% in Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2 Hy024’ The net rate of return on non-financial companies has fallen from 11.3 per cent in 2014 to 8.8 per cent in 2024. The estimated rate of return on capital is not the reciprocal of is not the same as shares of profits within national income, yet it illustrates a direction of travel consistent with the data on rising shares of accounted by labour.

The net rate of return for private non-financial corporations has decreased in April to June 2024

There are two significant inferences to be drawn from the changes in wages within national income and falling profits and rates of return on capital. The first is that the systematic reforms to improve the functioning of the British labour market and its product markets did not result in structural damage to labour as a factor share within national income. In short it gave people the opportunity to have a job and earn an income, which has been reflected in a rising share of wages within national income. The fall in profits as a factor share and the fall in the rate of return on capital also carry an inference. In circumstances of open capital markets where any realistic investment proposition can attract international capital to finance it, suggests that the level of private investment and capital accumulation in the UK, reflects the realistic rates of return and investment opportunities available in the UK. This suggests that an attempt artificially to raise the rate of investment in the UK will result in disappointing returns on capital.

Lower profits within GDP and lower rates of profitability, do not suggest that the UK offers many unexploited opportunities for profitable investment that are being presently neglected.

In the 1960s there was an anxiety among British policy makers and economic commentators that business investment in the UK economy was lower than in other economies. This contributed to the establishment of the National Economic Development Council during Harold Macmillan’s Conservative Government in the early 1960s and the Department of Economic Affairs and the National Plan by Harold Wilson’s Labour Government between 1964 and 1966. A set of naive and unrealistic objectives were developed, very much on the basis of the NEDC’s paper Conditions for Faster Growth. Lord Kaldor was heavily involved in framing economic policy in the 1960s Labour Government, yet he flagged the central flaw in attempts to raise investment through artificial policy inducement. Lord Kaldor in the 1960s looked at the proposition that the relative performance of the British could be explained by a relatively low share investment within GDP. His conclusion was that the reason the share of GDP, accounted for by investment, may well reflect the fact that the UK was a mature economy and a lack of investment opportunities that yielded adequate returns. By extension he argued that attempts to raise investment through policy would result in low returns on capital and would not result in much of an increase in GDP. Familiarity with Lord Kaldor’s realism would benefit contemporary policy makers and economic analysts.

Warwick Lightfoot

28 November 2024

Warwick Lightfoot is an economist and was Special Adviser to the Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1989 to 1992.