Kaput: German and European Economic Institutions set up for economic success sixty years ago are now in a Structural Slump

Germany’s economic miracle ended years ago, Germany and Europe’s Mercantilism, Rigid Fiscal Rules and resistance to technology need to go

Germany offers us seventy years of fascinating economic history. Much economic history is the exploration of nuances of data, using proxies, such as iron production and miles of railway lines as indicators for modern national accounts. It is recondite, contested theses of explanation that attempt to account for things, such as the 16th century price revolution, the impact of transcontinental railways, the economic viability of slavery in Ante-bellum American South and the diffusion of technology as part of the industrial revolution.

In contrast German economic history since the 1940s is a story painted in vivid colours. The West German Economic Miracle, the monetary history and practice of the Bundesbank, the evolution of the GDR’s socialist economy, the unification of the two Germanies, the one for one German monetary union, ahead of the abolition of the Deutsche Mark, the travails of German unification, within the context of a wider economically sclerotic European monetary union, are arresting economic events that invite exploration.

Wolfgang Munchau has brought Germany's post-war economic history up to date in a concise book with an unambiguous title Kaput: The end of the German Miracle. For many years Munchau was a journalist at the Financial Times, variously covering economics, EU affairs, and the introduction of the European Single Currency in 1998. Since 2022 he has written a stimulating column for the New Statesman. Munchau has for more than twenty-five years been a distinctive German voice in exploring the German Ordoliberal Social Market Economy. His latest book brings his long standing critique of Germany’s chosen economic model up to date. The Ordoliberal tradition that was framed in response to the National Socialist economic platform of autarky, intervention and erratic controls. It served West Germany well in the 1940s and 1950s yet had probably begun to run out of road by the late 1970s and certainly by the 1980s. Munchau has been unsparing in cataloging the manner in which the German Social Market Economy and its legalistic framing of policy has succeeded in shunting both the German and the wider European economies into a railway siding.

Konrad Adenauer and Ludwig Erhard the parents of the West German Economic Miracle

The West German Economic Miracle

It is a story in two halves. For forty successful years West Germany successfully rebuilt its economy, influenced by a combination of realism and caution. These were fortified by two positive shocks to the supply of labour available for the manufacturing sector. An influx of population from former territories of the German Reich and the wider diaspora of German colonies historically located across central and eastern Europe; and a still significant rural based population in West Germany that was available to be absorbed into an expanding manufacturing sector that had much higher levels of value added.These benign features of the post-war West German economy were further supported by the upheaval that followed the collapse of the German Reich in 1945. It was possible to look again at institutions, class relationships, the management of industry and the way that trade unions bargained in post-war West Germany. Similar changes occurred in Japan after its defeat in 1945. Their significance in radically freeing previously sclerotic social institutions was identified by Moncur Olson and explored in his books The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups in 1965 and The Rise and Decline of Nations in 1982.

In 1948 Ludwig Erhard both liberalised all prices and issued a new currency. This resulted in prices in the American, British and French occupied sectors of West Germany being set in response to conventional pressures of supply and demand. The results were that markets cleared and shortages and black markets disappeared. The new currency controlled inflation having brutally cleared away previous overhanging debt. These changes initiated by Kronrad Arenduer and his economics minister Ludwig Erhard succeeded in the face of opposition, and cautionary advice of the American and British occupation authorities. The combination of realistic prices, low inflation and a fixed exchange rate in the 1950s and 1960s set off an export-led recovery in output. This resulted in a structural balance of payments surplus that was not adjusted away through a rising exchange rate that was fixed against the dollar, under the Bretton Woods regime. The competitiveness of West Germany within the Bretton Woods fixed parity regime was entrenched institutionally, by writing the Bundesbank’s independent status into constitutional law in 1957.

The West German, Bonn based republic, was a model of civic democratic success. A stable functioning prosperous democracy that delivered affluence for its citizens in contrast both to the Weimar Republic and the Communist East German Democratic Republic - the GDR. Post-war West Germany was a model of success and stability for Europe and North America. High living standards, strong growth and financial stability were the hallmarks of this success. Moreover, as the international post-war Keynesian welfare model began to run into difficulty, at the end of the 1960s, as its various pressures and contradictions began to present themselves in terms of misaligned exchange rates and inflation, the Deutsche Mark was a candidate for revaluation.

When the US broke the dollar’s link to gold and the Bretton Woods parities collapsed after 1971, the advanced economies exhibited distress and inflation. West Germany was one of the few oases of relative financial stability. Rising and unstable inflation in advanced economies began to be associated with rising unemployment and stagflation. West Germany with its strong exchange rate, balance of payments surplus and perceived low inflation, appeared as an oasis of financial calm. The West German economy was identified as a locomotive economy that could, with the Japanese economy, lead the advanced economies out of recession in 1977.This was probably the high point of West Germany’s economic success.

West Germany the envy of the world

In the public’s mind West Germany remained visibly a great success. The Volkeswagens were reinforced by Audi and BMW as icons of YUPPY success. Visitors to West Germany admired its public space and cultural infrastructure. Berliner Philharmonie Concert Hall’s vineyard seating around the orchestra, became the model for future concert halls such as the Sydney Opera House in 1973 and the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles in 2003. From an American or British visitor's perspective what impressed them was the public investment in the arts, not least opera. The Deutsche Opera in its new brutalist opera house in West Berlin represented the acme of modernity. It was, moreover, the vitality of West German opera that impressed. Some 170 new operas after the Year Zero in 1945. Visitors were also impressed by the range of opera available in provincial towns and cities compared to what was available in Britain or the USA.

West German was a paradigm of civic, democratic and economic success. Left of centre British politicians admired the success that the SPD reaped in the 1960s, after it had repudiated its marxist inheritance in 1959 at its Bad Godesberg convention. While in the 1970s Conservative politicians, who were later to serve in Mrs Thatcher’s cabinets, such as Sir Keith Joseph and Sir Geoffrey Howe invoked the success of the West German Social Market Economy, as a model for British economic reform as the tip toed towards UK abandoning the partly nationalised mixed economy constructed in the 1940s.

In the 1980s the Labour politician John Smith, as shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer chose to describe himself as ‘a German nut’, so strong was his admiration for West German public policy and its economic policies in particular. This was probably the high-water mark of West Germany’s Rhenish capitalist model. By the late 1980s its structural weaknesses that had been present for sometime were beginning to present themselves. West Germany had a significantly regulated economy where policy was framed in a highly legalistic policy culture. Rules flowed naturally from its Ordoliberal tradition.

A mercantilist economic culture modelled on the tradition of Prussia’s Julius Tower

It was in many respects a mercantilist economic culture that celebrated saving, investment and accumulation over consumption. In the 1950s persistent public sector surpluses were caricatured as ‘Julius Tower ‘policies. Bonn politicians accumulated budget surpluses for little economic purpose in the manner that Prussian Kings had stored treasure in the Julius Tower, at their fortress in Spandau. The backbone of this mercantilism in the 1980s was the Bundesbank’s unflinching commitment to price stability that ensured Germany remained competitive in export markets in Europe and in the wider international economy.

It also gave West Germany a sense of pride and brio in international monetary affairs. After the collapse of Bretton Woods in 1971 the Deutsche Mark was consistently one of the strongest currencies trading on foreign exchange markets. The Deutsche Mark was the currency that anchored the attempts to stabilise the EEC currencies. in the 1970s and 1980s. Whatever shock knocked the European Snake in the 1970s or the European Monetary System between 1979 and 1993 the Deutsche Mark was always revalued. Currencies such as the Italian Lira, Sterling and the French Franc came in and passed out, but the Deutsche Mark sailed on at a higher rate.

In the second half of the 1980s several European countries decided to emulate the discipline of the Bundesbank. Irritated and embarrassed at having to devalue their currencies within the EMS, they embraced domestic monetary policies modelled on the rigour of the Bundesbank.The principal example of this was France that embraced the Francfort policy of monetary orthodoxy with all the enthusiasm of a convert, transforming France financially into the strongest economy in Europe in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Ordoliberalism and Social Market Economy take on characteristics of a straight jacket

While West German policy makers continued to ride high their Social Market Economy was already beginning to exhibit a form of permanent structural recession. West Germany had in the 1960s and 1970s developed a generous welfare state, based around high employment, high wages and public sector pensions that reflected high industrial wages negotiated by union and employer organisations. The result was a steady incremental creation of an industrial and business culture that was not flexible, that placed trade union workplace sensibilities at the centre of the day to day management of businesses. Grand Christian Democrat-SPD Coalitions in the 1960s and SPD led governments in the 1970s, raised public expenditure, the tax burden and payroll social security taxes to finance increased public sector generosity. The result was that by the 1980s the West German economy in terms of labour markets, supply performance and economic growth was increasingly sclerotic. In the 1980s West Germany’s economic performance was disappointing compared to that of the UK and USA, when both economies went through a period of sustained supply side reform that changed their labour markets, industrial relations and lowered marginal tax rates.

The West German Economic Miracle was a story of remarkable recovery against the perceived odds of success. It was based around rapid reconstruction of the capital stock and powerful structural adjustment in labour markets. Between 1947 and 1950 wages rose by 15 per cent while consumer prices rose by 14 .3 per cent, and labor productivity rose by 17.7 per cent.

In an article in the International Business & Economics Research Journal published in 2010 Germany: Twenty Years After The Union Pete Mavrokordatos, Stan Stascinsky, Andrew Michael vividly sets the story out : ‘This success continued between 1950 and 1960, during which time the GDP doubled, worker productivity rose by 75 per cent, and there was virtual price stability. This growth was accompanied by only one significant recession, which was in 1957-58. What were the factors contributing to this unbelievable success? Demand for German goods was very strong pushing exports up by 17.5 per cent. The strong demand for goods was fueled by a relatively loose monetary policy. On the fiscal side, policy during 1952-56 created a budget surplus of more than 3 per cent of GNP. In short, during the years 1950-1955 the German economy performed amazingly. ….West Germany’s economic performance reached its peak during the period 1969-1973 a period known as the German economic miracle’

Around 1970 West Germany began to experience capital utilization constraints and upward labour market pressures on wages. West Germany miracle or no miracle, was not immune from the international labour market that followed radical unrest set off in France in May 1968. Inflationary pressures started to emerge. Germany experienced annual rates of inflation of around 6 per cent in the early 1970s. It was not as bad as the inflation that emerged in other advanced economies such as France, Italy, the UK and US, but it was a signal that something had changed. A significant change that took place in the 1960s and early 1970s was a growth in the size of the public sector and with it the tax burden. Pete Mavrokordatos, Stan Stascinsky, Andrew Michael point out in their article that in 1960 government spending accounted for 32.9 per cent of the GNP, but by 1973 this ratio had risen to 42.1per cent. While taxes and social security rose, by over seven percentage points, from 35.9 percent of GNP in 1960 to 43.3 per cent of GNP in 1973.

West Germany was a rich high income economy, with a large public sector that was beginning to lose its dynamism and flexibility. West Germany had some of the lowest rates of GDP growth among the principal advanced industrialised economies between 1973 and 1989. Unlike the 1950s and 1960s there were two major recessions - 1974-75 - and -1981-82. Both these recessions were distinguished by disappointingly slow recoveries in output. This disappointing growth partly resulted from the tight monetary policies that the Bundesbank applied to control inflation. The central bank demonstrates that the relative price effects generated by adverse commodity price effects do not have to be passed into the domestic price level one for one, if the central bank applies a determined and non-accommodating monetary policy. The overall West German economic story in the 1980s was sclerosis and formed part of a wider European economic sclerosis.

Eurosclerosis in the 1980s

West Germany and its continental European partners in the European Community exhibited a common eurosclerosis in the 1980s. They became increasingly nervous about competition from economies that were not handicapped by a powerful corporate culture dominated by trade union sensibilities and nor burdened by expensive publicly financed welfare states. At the end of the 1980s within the EC this anxiety took on a parochial dimension. The main long-term competitive threat to economies such as France, Germany and Italy came from North America and the dynamic economies of Asia such as Japan, Taiwan, Singapore and South Korea. Yet the immediate local focus of attention in the EC, in the second half of the 1980s, was the decision in 1986 to create a Single Market to increase the ease of trade within the European Common Market and its customs union.

Norbert Blom and West Germany’s opposition to social dumping

The combination of easier trade within the EC invited immediate concern about the threat to West Germany’s Rhenish model of high social costs. Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Spain and the UK were perceived as competitive threats in the new Single Market that took effect in 1993. German ministers were in the vanguard of getting the European Commission to develop an agenda of regulation that would have the purpose of imposing EC regulations that would raise the costs of Germany’s competitors in Europe, so that their industries could not take advantage of a competitive edge that arose from lower social costs. Norbert Blom, the long-serving German Conservative CDU Social Affairs minister, was determined that there would be ‘no social dumping’ within the coming Single Market. This led to the European Commission’s Social Action Programme of nineteen proposed draft directives, tabled by Mrs Papandreou in 1989, the proposed European Social Charter and the Social Chapter of the Maastricht Treaty signed in 1992. At a time when the European Commission was exploring a monetary union that would require greater flexibility in product and labour markets, it embarked on a social action programme that would entrench policies and regulation that would make them less flexible. This was a recipe for slower economic growth and higher structural unemployment.

Fortress Europe and the European Commission's Perception of the Asian Peril

If the European Social Action Programme and the Europe Social Chapter were the parochial manifestation of Germany and Europe’s anxiety about competition that could threaten expensive social models, such as those in France and Germany, there was a wider agenda of international mercantilism and protection that the EU pursued from the 1980s. This built on longstanding EEC protectionism based on agriculture and relatively high external tariffs in the 1960s. In the Delors Commission it was expressed as an ambition to create a Fortress Europe that shut out unwelcome competition. In the 1980s and 1990s much of this anxiety about Asian competitiveness focused on Japan. Edith Cresson the Socialist French Prime Minister, expressed it in extraordinary terms in May 1991 when talking about trade and Japan she said that the Japanese were like ‘yellow ants trying to take over the world.’The European Commission expressed it in a more formal way in the Delors White Paper on Growth, Competitiveness and Employment in 1993. A central proposition of the Commission paper was that David Ricardo’s principle of comparative advantage was no longer relevant to trade and modern economics. While the social action programme resulted in domestic EU regulation that made Europe’s markets less flexible, the European Commission’s trade policies worked to limit the effects of international competition on Europe’s markets through trade.

The superficial hopes of the authors of the Padoa Schioppa report on the economic benefits of the monetary union and the Cecchini report on the growth potential of the Single Market in the late 1980s failed to materialise. The EU and later the euro-zone’s economic performance was disappointing. These failures were cataloged in a report prepared for the European Commission by Andre Sapir, a Belgian economist, An Agenda for a Growing Europe, published in 2004. Sapir later reviewed the progress that the EU had made in implementing recommendations that report in the Journal of Common Market Studies in 2014, little had changed. That conclusion is reinforced in the latest report examining the functioning of the EU economy The Future of European competitiveness : Report by Mario Draghi published by the European Commission in 2024.

Venetian Graffiti expresses scepticism about Fortress Europe

German Unification 1990

Just as the Single Market was about to take effect in January 1993, German policy makers became absorbed in a German question of huge historical importance. German unification was a matter of great importance to German politicians throughout the post-war era. People interested in Germany underestimated its significance to Germany. To most people outside it appeared a remote theoretical possibility, not worthy of serious discussion.

Helmut Kohl the Federal German Chancellor in 1990 - Cometh the Hour, Cometh the Man

Yet for West German politicians it was a live issue. The Bonn Republic, as West Germany was sometimes referred to, was based in Bonn in the Rhineland. Yet the old Reichstag building that happened to be located in West Berlin was carefully rebuilt after the war. What is more symbolically, it flew all the flags that the German Lander of the Reich flew, before the allied partition of Germany into sectors in 1945. These included the flags of East Prussia and Danzig. This reflected the fact that given that there had been no comprehensive peace treaty after 1945, in international law, technically, the borders of Germany were those of the German Reich in 1937.

Indeed the German Basic Law that governed West Germany was framed as a constitution for the whole of Germany. Moreover, the West Germany’s Federal Republic of Germany from 1949 to 1970, asserted the principle of the Exclusive Mandate, that it should be ‘the only German government freely and legitimately constituted and therefore entitled to speak for the German nation in international affairs’. The concept of the Exclusive Mandate evolved into the Hallenstein Doctrine ( named after the State Secretary at the Foreign Affairs Ministry, Walter Hallenstein) that the Federal Republic of Germany would regard it as an ‘unfriendly act’, if third countries recognised the GDR diplomatically, with the exception of the Soviet Union. The doctrine was impractical and abandoned by Willy Brandt as part of his Ostpolitik after 1969. The doctrine, however, illustrates how embedded the aspiration of uniting the two Germanies was, on the basis, of the institutions of the Bonn Republic.

European politicians gave German unification little thought, when it became practical politics there were reservations rather than celebrations

Most European politicians considered the possibility of reunification, for all practical purposes dead. When it was mentioned they could express fear and animosity about the idea in the way that the Italian President did in the mid 1980s. Giulio Andreotti the Italian Prime Minister warned against a revival of ‘pan-Germanism’ and joked ‘I love Germany so much that I prefer to see two of them’. This recalled the Nobel Prize winning French novelist Francois Mauriac’s famous quip that ‘I love Germany so dearly that I hope there will always be two of them’. Mrs Thatcher’s reservations about German unification were strongly expressed and well known. President Mitterrand shared her views, perhaps, even more trenchantly, but expressed them more guardedly in public. At the EC Summit the Dutch Prime Minister Rudd Lubbers intervened in the form of a question that spoke for many other heads of government. Lubbers asked ‘On the basis of the past, is it opportune for Germany to become united again?’ Kohl wanted to force an agreement to support unification and was angered by with Lubbers’s intervention. As the dinner ended Kohl is recorded as having growled at Lubbers that ‘I will teach you something about German history’.

The collapse of Soviet power in central and eastern Europe took place in 1989. Events were swift. First there was the Solidarity Revolution in Poland, then there was the opening of Hungarian borders and then East German demonstrators demanded that the inner-German border was opened in Berlin in November 1989. West German politicians were quick to alight on the opportunity to reunite Germany. The leaders of the East German GDR democracy movement were more ambiguous about embracing West German consumerism. The GDR reform movement - groups such as New Forum and Democracy Now - that joined Socialist Unity Party in a Round Table that was to meet sixteen times, would have preferred a version of a socialist state in the GDR, with human rights, freedom of assembly and freedom of international travel.

Walter Ulbricht’s Cathedral: the acme of GDR Technological Achievement, the Television Tower constructed in East Berlin between 1965 and 1969, whose globe took on the form of a Christian cross when the sun shone on it

The reform movement happily co-operated as part of a round table with the GDR’s governing Socialist Unity Party (SED) in the Summer and Autumn of 1989. Katja Hoyer in her book Beyond the Wall East Germany,1949-1990 summarises the position concisely: ‘many of those who had opposed the SED regime were not fundamentally averse to the GDR’s economic system. There was much talk of a third way between socialism and capitalism’. But Germans living in the GDR immediately wanted the consumer goods that were in West German shops. East German GDP was a fraction of West Germany’s at market exchange rates. People saw on their TVs every night the consumer goods that the GDR’s socialist economy had failed to give them over more than forty years. In a reversal of Leninism it was the people in November 1989, who were in the vanguard of change.

Kohl, a Bonn politician in a hurry struck while he had the unification wind in his sails

Helmut Kohl, the West German Chancellor saw the opportunity for German unification as a decisive historical moment, where he needed to act swiftly to obtain East German consent on West German political and economic terms. The key to that East German public consent was using West German money to raise East German living standards immediately. The start of this process was a one for one German monetary union, with a separate exchange rate for larger savings accounts. At a stroke on 1 July 1990 East Germans with money could spend them in West German or in the rest of the world at the same exchange rate as the Deutsche Mark. This transformed the immediate power of East German households to consume. Many households had savings accumulated over years, given that in the GDR there was little to spend money on. The process of unification that Kohl had envisaged, as taking place in stages over ten years when Kohl had presented his ten point plan for unification on 28 November 1989, was dynamic. The GDR ceased to exist at midnight on 3 October 1990.

The German Monetary Union may have increased the economic power of East Germans to consume, but it devastated the capacity of firms and people of working age to produce, sell their labour and output, given that East German productivity was around a third less than that of West Germany. The monetary union placed economic agents in the GDR in a monetary straight jacket analogous to that of British industry in the 1920s when Winston Churchill returned to the Gold Standard at the pre-war 1914 parity.

The position of the economic agents in East Germany was worse because there was no easy practical exit from the defective monetary regime, such as leaving the Gold Standard as Britain did in 1931 and France did in 1936. Moreover, the wider economic terms of German unification prevented East German product and labour markets from adjusting their internal prices in response to the adverse permanent monetary shock. The wages and salaries of public sector employees were raised to the same level as in the West German Lender. Social security transfer payments, such as old age pensions and unemployment benefits were raised to the West German level. Wages in private sector firms were incorporated into the Rhenish model of corporatist collective bargaining and raised towards West German rates of pay.

The result was that East German private sector pay was higher than any realistic assessment of East German marginal revenue product. This was a recipe for making any enterprise that marketed its output bankrupt and creating unemployment. Not only did people lose their jobs but high real wages that did not adjust to their realistic marginal product, ensured that labour markets could not clear, creating structural or permanent unemployment. This was further aggravated by social security payments to unemployed households that were above the wages they could potentially in the labour market outside the public sector.

East German lender household incomes and consumption swiftly rose in relation to West Germany in the 1990s.They approached around two thirds of the West German level. East German GDP per capita rose from around a third of that of West Germany in 1991 to 61 per cent in 1997, driven by subsidies for construction, but then growth trailed off. This represented a huge increase in economic welfare compared to 1990, yet it was in a context of economic stagnation. There was only a very slow further natural market catch up with West Germany, because economic policy, regulation and wage bargaining institutions hindered progress in raising living standards and employment. Many people of working age left the Eastern Lender to live and work in West Germany. The economic transition in other former socialist economies that bordered the GDR appeared twenty years later to be more successful and exhibited fewer structural problems in labour and product markets. By 2009 there were examples of Germans that lived close to the Polish border working in Poland, while living in Germany because work was available in the Polish economy and rents were cheaper in the east German border communities.

The Caring Hand that Cripples

The process of political and economic unification decided by Helmut Kohl and his colleagues resulted in swift political and economic results that came at the expense of longer term economic stagnation. Part of the explanation was the deliberate purpose on the part of the ‘social partners’ - the West German trade unions - to prevent industrial companies in the west from facing competition from plants being set up in the east that could take advantage of lower wages and other costs. This trapped East German product and labour markets into economic inactivity that would take decades to rectify. It was the local German version of West Germany’s approach to the construction of the European Single Market - an agenda of anti-social dumping to be brought about by locking poorer low productivity into regulation and social costs that would vitiate their ability to catch up through the normal operation of properly functioning markets where prices approach the position where they clear. In turn this was the approach taken by the EU in relation to international trade negotiations on matters such as trade in agricultural products and textiles.

There were huge payments made to improve the infrastructure of East Germany. Everything from roads, railways, public buildings and the East German housing stock received investment financed by West German taxpayers. Yet this physical investment failed to stimulate dynamic and sustained growth in value added produced in the East German lender. Industrial subsidies intensified structural unemployment, by subsidising the capital investment at the expense of already costly labour. The enormous subsidies created a negative cost of capital. The result was a falling rate of return on capital in East Germany.

The consequences of these policies were set out in a paper The Caring Hand that Cripples: The East German Labor Market after Reunification (Detailed Version) by Dennis J. Snower and Christian Merkl economists based at the Kiel Institute in 2006. Their conclusion is arresting.

‘This paper provides a sober assessment of the East German labor market problem, suggesting that this problem has been exacerbated by various forms of "care" that the East has received from the West: support in bargaining, unemployment benefits, and job security provisions, in particular. Our analysis also implies that it is pointless to wait for the problem to disappear of its own accord. In the absence of fundamental policy reform, the damage is permanent, not temporary’.

Unemployment doubled from 10 to 20 per cent between 1991 and 2004. The share of long-term unemployment rose from a quarter to a half of those out of work. In the ten years to 2006 East German GDP grew at a similar or lower rate in the West. This disappointing performance came despite hugely generous fiscal transfers from West Germany. In 2000 these were averaging around 4 per cent of German GDP, with half of the transfer payments going to finance social security payments. Around a quarter of East German private consumption was financed by West Germany after fifteen years after unification.

The combination of financing this infrastructure investment and the social security transfer payments made to households living in the former GDR imposed a heavy burden on West German households. This was exemplified by the unity tax. West German residents resented this burden and despised former citizens of the GDR. In the mid-1990s the joke in the executive dining room of Volkswagen's corporate headquarters in Wolfsburg was that they would like the inner German border to be rebuilt - even if it was only one metre high.

There was also a growing edge to West German resentment of the burden of financing the East German transition to a market economy. Not least because it had resulted in East German pensioner households having higher pension incomes than those in the West. This arose from the fact that in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s there has been significantly higher labour market participation by women in the East than in the West. The result was that the average pensioner household in old GDR had accumulated more years of pension entitlement in relation to their incomes than those in the west.

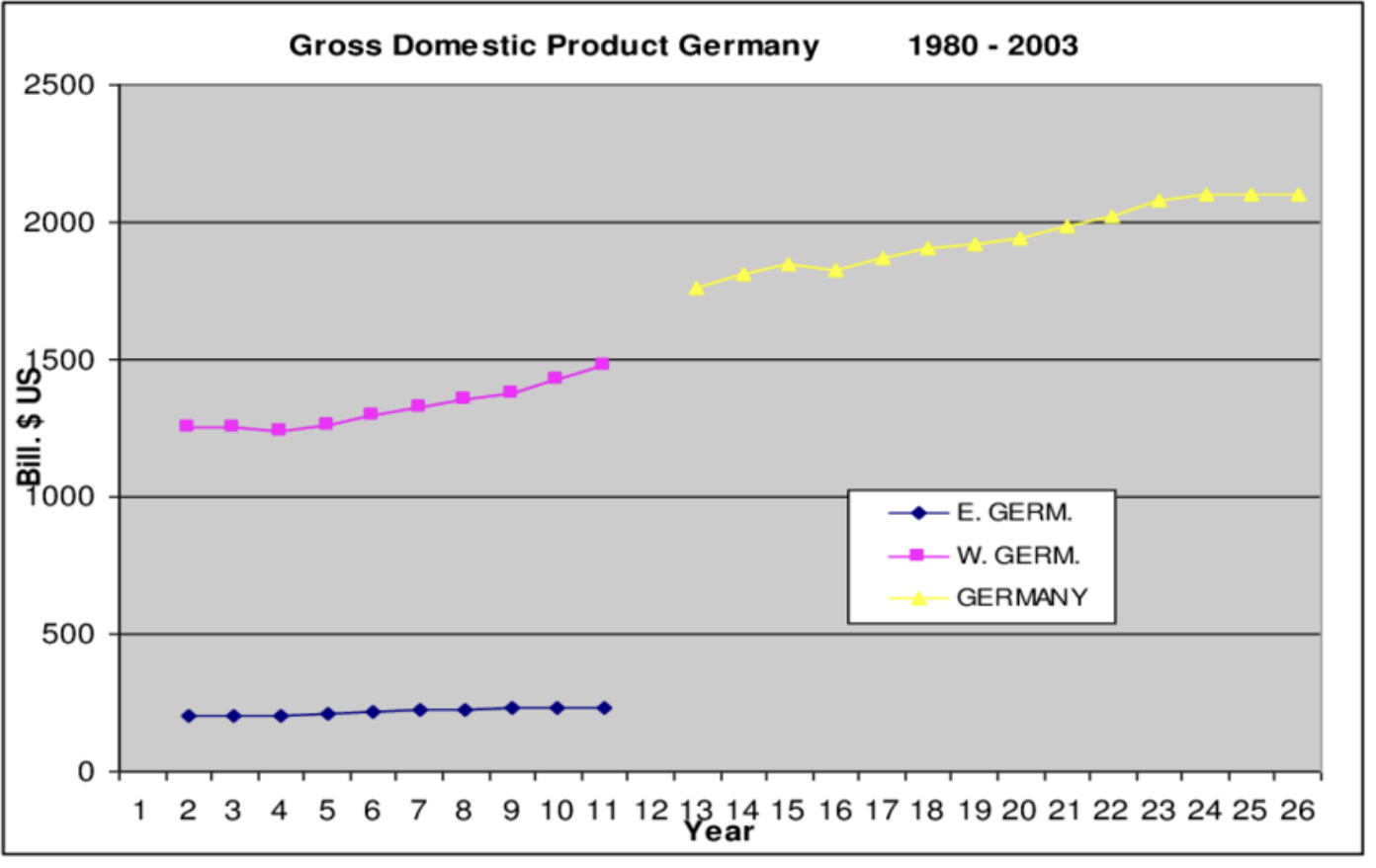

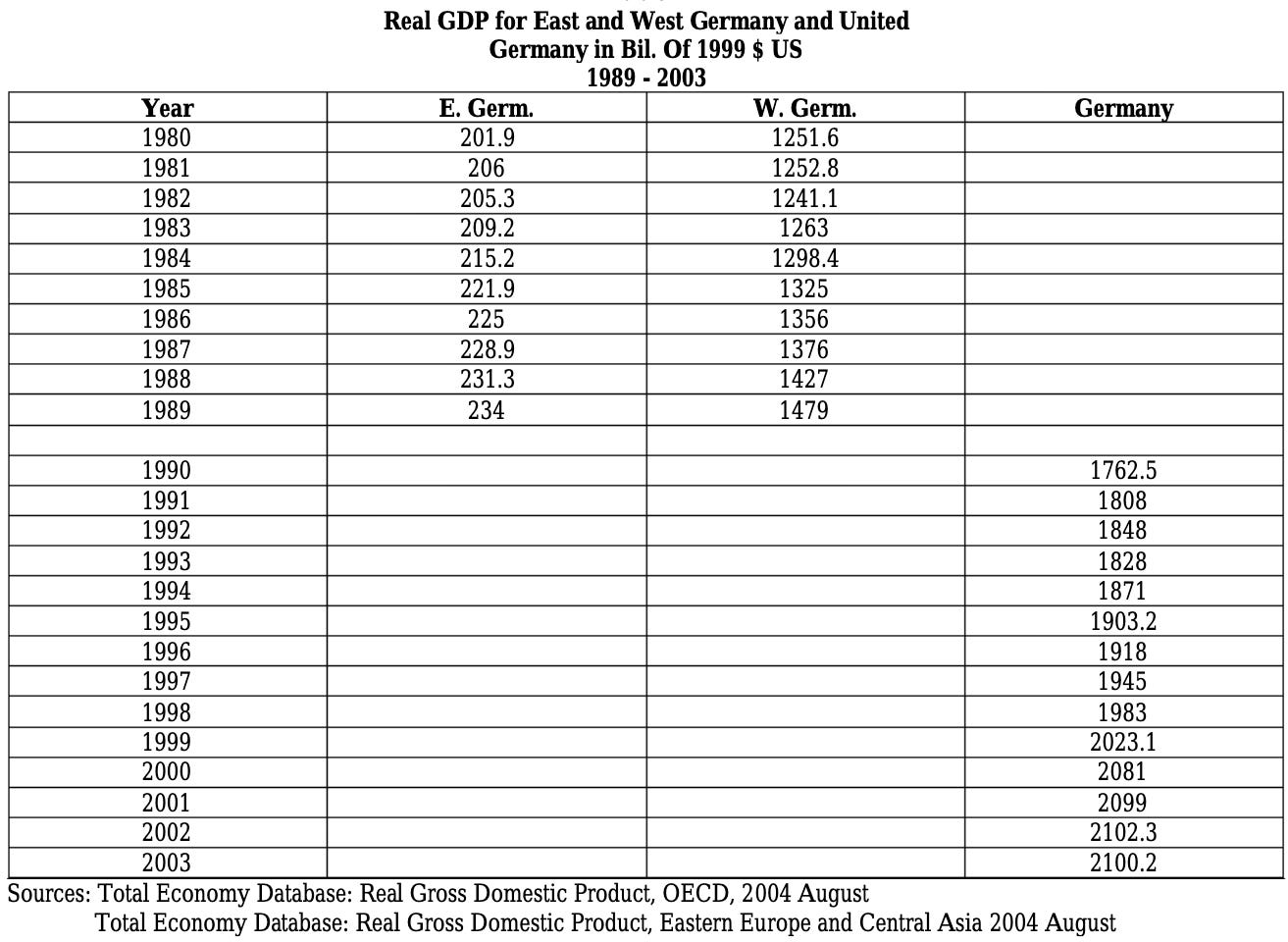

The two tables taken from Germany: Twenty Years After The Union published in International Business & Economics Research Journal in 2010, illustrate how the days of extraordinary growth were over for West Germany by the 1980s and how after unification once the initial rapid catch up phase of economic growth in the eastern German lender faded in the mid-1990s, German economic growth was anemic at the start of the millennium after 2001.

Social alienation in East Germany

The process of transition resulted in high levels of anomie and social alienation in the east. The combination of high structural unemployment, seeing the GDR’s uneconomic socialist industrial structure dismantled, experiencing continuing depopulation and being patronised by residents in the West became a toxic cocktail of disappointment. This exhibited itself in a rejection of West German consumerism. Part of this was the emergence of a nostalgia for processed and manufactured products that had been part of everyday life in the GDR. This contributed to a corrosive GDR nostalgia exhibited in the film Good Bye, Lenin! made in 2003. The political potency of this alienation and nostalgia is clear. It has been translated decisively into votes for the Die Linke Partei and the Alternative fuer Deutschland in successive elections in the East German Lender.

Die Linke’s offices in Potsdam

German unification did not pose an impossible burden on the West German economy, the investment and transfer payments were in principle manageable. In many respects unification and its consequences, however, exposed something that was much more difficult. This was a reluctance to change and adjust to new circumstances. Much of the West German approach to East Germany was carefully constructed policies to ensure that unification, whatever else it did, would not involve direct challenges to the Rhenish corporatist model’s long-standing arrangements. Arrangements that themselves had been creaking at the edges for almost two decades by 1990.

iGerman unification does not in itself explain the disappointing performance of the German economy and the railway siding that its Social Market economy has been shunted into. The reluctance of the West German social partners to accept social and economic change arising from the disruption and costs of the unification process, raised its economic costs as well as its financial costs. While the conduct of macro-economic policy adhering to the tenets of the Ordoliberal legalistic culture that the old Bonn Republic had adopted in the 1950s aggravated the costs of the transition.

Thomas Mann’s ‘not a German Europe, but a European Germany’

Helmut Kohl was determined in the Autumn of 1989 to seize the opportunity to unite the two Germanies. Kohl turned out to be the true heir to the Hallenstein Doctrine. To get consent for unification among West Germany’s EC partners Kohl framed it as an agenda of German unification within a wider agenda of European unification. The mantra that German politicians invoked was Thomas Mann’s aspiration of a united German rooted in the institutions of Europe. Helmut Kohl was to embrace Thomas Mann’s words in part because of the serendipity of the Delors Report on monetary union in 1989. If it had been business as usual, the Bonn Republic would have mounted a fierce opposition to a European Single Currency, few people expected the West Germans to give up the Deutsche Mark whose success in 1949 had been central to its Economic Miracle in the 1950s.

The serendipity of the Delors Report on European Monetary Union in 1989

Germany’s unexpected unification in 1990 coincided with an important point in further European integration. Europe’s proposed monetary union had nothing to do with German unification, as such, it had a much longer genesis. A European monetary union had been an EEC aspiration since the late 1960s. The instability of exchange rates in the late sixties as the Bretton Woods system became unstable played havoc with fixed farm prices set in national currencies as part of the European Common Agricultural Policy. The recommendations of the Werner report set in 1969 for full economic and monetary union were accepted by the European Council at its Paris meeting in 1972. In practical terms they were blown apart by unstable inflation, exchange rates and different national monetary responses to both the collapse of the Bretton Wood parasites against the dollar and the oil price crisis in 1973. These sank the EEC essay in exchange rate management the European Snake. In 1978 ideas for a European Exchange Rate mechanism were revived. This took effect in April 1979 as the European Monetary System. It worked well. The Deutsche Mark was its anchor, currencies converged on it, by replicating the Bundesbank’s monetary policies, this contributed to lower inflation across the EEC. There was an asymmetry in the operation of the system Exchange Rate Mechanism which arose from the obligation of countries to take monetary and other policy action if their exchange rate was weakening against the Deutsche Mark. This caused great irritation to other countries, such as France, because they did not like the embarrassment and political opprobrium of effectively devaluing their currencies against Germany’s anchor currency. This resulted in a committee of experts being set up in 1987, chaired by the President of the European Commission Jacques Delors. It reported in 1989 and called for a monetary union.

In 1990 the prospect of German unification was publicly welcomed by continental European leaders. Yet it privately horrified several of them. Not least the French President Francois Mitterrand. The whole political purpose of the European project from a French perspective was to economically bind Germany to France with, for example, joint policies on coal and steel, the vital materiel of war, to contain Germany power. A divided Germany had made this task much easier during the two generations that followed 1945.

President Mitterrnad’s Financial Maginot Line: the Euro

President Mitterrand embraced European economic and monetary union and the Delors Committee’s proposed single currency as a route to emasculating German economic power in the face of the prospect of unification. French policy was based on a naive proposition. Post-war West German economic success was based on the success of the Deutsche Mark and the Bundesbank. Abolishing the Deutsche Mark by subsuming it into a wider European Currency and diluting the effective influence of the Bundesbank within a European System of Central Banks would contain German economic power. It was a mistaken proposition because the capacity of a united German to deploy its economic power for geopolitical purposes, would arise not from its monetary and financial arrangements but from real economic resources. These in turn would reflect things such as Germany’s population, the extent of its human and physical capital, its technology base and its capacity to maintain a comparative advantage in the manufacturing industries that are central for the production of war materials. President Mitterrand was embracing a late 20th century version of a financial Maginot Line

The German Chancellor Helmut Kohl embraced European monetary union to obtain French and EC support for monetary union. Kohl was anxious to make swift progress on unification for three connected reasons. The German Chancellor saw it as a historical moment where the two Germanies could be united on terms laid down by the Bonn Republic. It was not certain in the Autumn of 1989 and the early months of 1990 that the new GDR leaders wanted to unite with the west on Bonn’s terms. They wanted Bonn’s money, because the GDR’s once successful socialist economy was collapsing. Moving swiftly to unite on Bonn’s terms after the GDR election that Kohl’s East German CDU won was important, before the mood changed and being able to stabilise the East German economy was an immediate policy imperative. Agreeing to the European monetary union and the path laid down in the Delors Report, removed French much anxiety, and certainly French opposition to the project.

The Ordoliberal Tradtion’s wider influence on European economic policy

To ensure that German supported the proposed European Single Currency and ratified the Maastricht Treaty, the structure of the new monetary union and its phased time table, were framed to reassure German sensibilities about ending the Deutsche Mark and vitiating the effective monetary control of the Bundesbank, but not its influence. Price stability would be the new European Central Bank’s policy objective. There would be no lender of last resort function and bailing out of national economies’ fiscal deficits was made unlawful. These were written into the Maastricht Treaty. They made the new central bank more independent than an independent national central bank, because it would require a treaty change to modify its objectives and position. The phased staged conversion called for low inflation, stable exchange rates within the ERM narrow bands, and deficits of no more than 3 per cent of GDP and stocks of public debt of no more than 60 per cent of GDP. There was some wriggle room in the surveillance of these criteria. Their purpose was to keep EC countries out of the new monetary union that were regarded by Germany as monetarily and fiscally incontinent. These were the PIIGS - Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece and Spain. In the end it was France and Germany, paradoxically that had to engage in accounting sleights of hand to conform with the conversion criterion of the Maastricht treaty in 1998.

A permanent monetary union with no bail out rules and no lender of last resort function

The full merits and demerits of the European Monetary Union are beyond the scope of this article. However it is worth noting how much the German Ordoliberal orthodoxy informed the construction of the monetary union and its consequences for Germany and Europe. The convergence criteria were for narrow financial convergence at one point in time, not proper economic convergence of the sort that would normally be considered in examining the extent that the criteria of an optimum currency area had been achieved. It wrote into law terms that effectively ruled out the central bank having a lender of last resort function that would become an important handicap in the credit crunch and banking crises between 2007 and 2011. It effectively placed the whole of the euro-zone in a monetary straight jacket analogous to the straight jacket that the Eastern German lender found themselves in after 1990. The great merit of the EMS and Bretton Woods was that currencies could adjust when economic shocks and divergence of policy imposed disproportionately awkward stains resulting in unacceptable losses of economic welfare.

The structure and rules of the euro-zone have resulted in some countries having monetary conditions that were too loose, such as Ireland and the Netherlands between 1998 and 2007. While Germany had monetary conditions that were too tight, both in the 1990s in the run up to 1998 when policy converged and between 1999 and 2007. The no bail out rules meant that the central bank could not take sufficient action during the banking crises and the start of the Great Recession in the period between 2007 and 2011. While euro-zone surveillance of the Maastricht fiscal rules handicapped national governments in Europe from making full use of fiscal policy to stimulate their economies in the decade after 2010 when monetary policy had lost traction as a source of economic stimulus.

Germany's influence on Europe have entrenched institutions that would have served well in the 1970s, but have been past their sell by date for more than thirty years

In short the German Ordoliberal tradition framed the European monetary institutions and policy culture in a manner that legally set policy in a sort of aspic which prevented it keeping up with changing economic circumstances and contemporary thinking. A Bundesbnak monetary culture that had served West Germany relatively well in the inflation of the 1970s, was erected into a constitutionally entrenched principle of economic government when its time was passed.

The first political community that suffered the consequences of this was Germany itself. West Germany initially responded to the challenges of German unification by financing what needed to be done in the east, by borrowing. After 1991 the macro-economic consequences of eastern Germany's transition to a market economy were managed through a combination of tight monetary conditions to control inflation, and higher taxation to control borrowing. This contributed overall to disappointing economic growth, which in turn made it difficult for Germany to meet the convergence criteria for monetary union in 1998. Disappointedly slow growth suppressed the denominator of GDP used in calculating the deficit and debt to GDP criteria.

In the first twenty years after unification Germany needed a looser monetary and fiscal framework to spread the cost of unification over time. Instead Germany was locked into a monetary framework that was too tight in terms of domestic monetary conditions, aggravated by an exchange rate that was too high and could not adjust to Germany’s changing circumstances. While the fiscal rules of the Maastricht Treaty prevented the German Government from using its capacity to borrow to spread the fiscal costs of unification over a couple of generations.

Baleful Fiscal Rules in the EU - and Germany’s the debt brake

In some respects the legacy of the success of the post-war Bonn Republic's economic miracle has been baleful for modern Germany’s political culture. A good example of this is the balanced budget constitutional amendment passed in 2009. This limited the structural budget deficit to 0.35 per cent of GDP. Its purpose was to ensure that Germany would not exceed the Maastricht Treaty’s 60 per cent debt limit. This amendment to the German Basic Law was the first action of Anglea Merkel’s government, given the combination of debt incurred to finance the eastern German transition and the loss of tax revenue following the Great Recession in 2009. It amounted in economic terms to a pro-cyclical tightening of German fiscal policy at precisely the time that fiscal stimulus was needed when monetary policy had lost the traction to stimulate.economic activity.

Ostpolitik and Mercantilist Trade

A long standing feature of German policy during both the Bonn Republic and the united German Republic since 1990 has been a distinctive Ostpolitik. This started when Willy Brandt was Chancellor. It took off during the 1970s during the period of detente with the Soviet Union, was maintained by Helmut Schmidt and Helmut Kohl. It involved turning a Nelsonian blind eye to abuses of human rights in both the GDR and USSR. After the collapse of the USSR in the thirty years that followed it took a new form that concentrated on business and trade opportunities for German industrial exporters and importing cheap oil and gas from the Russian Federation. In the process under Schroder and Angela Merkel Germany became dependent on Russian gas supplies. The full extent of this exposure was evident in 2022 when the UKrainian war started.

The German economic Ostpolititk conformed to the mercantilist economic policy that has been the pattern since 1948. An emphasis on competitiveness in international markets, surplus on the balance of payments, balanced budgets and a suspicion of using the state’s power to borrow both in terms of economic management and in financing investment. In the 1950s and 1960s it served the Bonn Republic well. West Germany avoided the worst excesses of the post-war Keyenesian demand management that made the UK and US economies financially unstable and prone to rising prices where through a process of gearing up inflation was high and unstable.

By the 1980s high spending, high social costs and high taxation contributed to making the West German economy serotic. While the realism of the Bundesbank’s non-accommodating monetary policy ensured that increasingly structurally inflexible product and labour markets which resulted in slow productivity and economic growth, took place within a context of financial stability and low inflation. When France adopted West German monetary orthodoxy, the Francfort policy within the ERM, the results were similar: low inflation, slow growth and in France’s case high structural unemployment.

During Angela Merkel’s period of office as Chancellor the combination of the debt brake; the Ostpolitik dependence on Russian gas;the continuing mercantilist emphasis on export trade with China; conducted in a context where monetary conditions and fiscal rules were not framed to meet the needs of the German economy in terms of conventional Paretian economic welfare; resulted in a what Wolfgan Manchou borrowing from Edmund Phelps calls a structural slump.

A structural slump obscured by export opportunities in China and the Euro that makes Germany competitive in international markets

At various stages this ‘structural slump’ has been obscured by the continuing exporting success of Germany manufacturing. This has reflected three things. The emergence of China as the world's second largest economy and the huge export market that China has represented. The huge export that Germany made to reform its labour market and keep its export sector internationally competitive. The Herz labour market reforms between 2003 and 2005 represented a systematic attempt to maintain German competitiveness and improve the functioning of the labour market. While Germany’s export competitiveness both in Europe and in wider international markets has been supported by membership of the euro-zone that has held down the external value of the German currency.

In Geopolitical terms Germany has been an irresponsible bystander insouciantly disengaged

Economically it equipped Germany with the institutions for a highly successful manufacturing economy in an analogue age that prevailed fifty years ago. Politically it resulted in Germany being in geopolitical terms and irresponsible power. Many people are familiar with notions of dissatisfied powers, or disruptive powers or revolutionary powers. Germany was an irresponsible power.It would not spend on its armed services, because of its fiscal constraints aggravated by its Debt Brake after 2009. This led to the broomstick army that Ursula von der Leyen presided over as German Defence Minister. In a NATO exercise in 2014 the German army used broomsticks painted black attached to Boxer armoured vehicles. At that time 42 of Germany’s 109 Typhoon fighter aircraft were unavailable for use because of maintenance issues, 38 of Germany’s 89 Tornado bombers and 280 of Germany’s 406 Martens tanks were operational. Germany was in geopolitical terms a bystander, with neither the military resources, the interest nor willpower to contribute to the western alliance such as NATO

Over many years despite US concern in relation to its dependency on Russian gas Germany was insouciant, ignoring warnings about the Nord Stream pipelines. The US opposed Nord Stream 2 from its start in 201. When the US imposed sanctions on companies that were involved in its construction, Germany's finance minister and vice chancellor, Olaf Scholz, said he firmly rejects’ the US legislation imposing sanctions on firms involved saying ‘such sanctions are a serious interference in the internal affairs of Germany and Europe and their sovereignty. We firmly reject this’.

Germany, after unification, simply took little interest in the world beyond Europe. As one British civil servant explained, ninety per cent of German Foreign ministry officials and diplomats worked on European related matters. Only ten percent of the German Foreign Ministry was involved with engagement with the rest of the world.

Germany’s cautious and ambiguous relationship with science, technology and risk

Germany, while having a distinguished reputation in relation to technical engineering skills and development, in terms of modern science, R&D and technology, as Manchau points out Germany is something of a laggard. Part of this arises from the huge damage done to German science between 1933 and 1945, particularly to Germany’s mathematical sciences and to German physics. German science and innovation has also been held back by several aspects of the post-war culture that dominated West German politics. Catholic social teaching was very influential on the Bonn Republic and the sensibilities of the environmental and green movements were also powerful, and disproportionate anxiety about risk.. These have combined to create a powerful strain of antipathy to science, technical innovation and hesitancy about development in the biological sciences. This partly reflects the legacy of the Nazi dictatorship that heightens sensitivity about anything that relates to genetic research and biotechnology. This antipathy to technical progress in the biological sciences was evident from the hesitancy about vaccination during the Covid public health crisis.

This distinct German sensibility contributed to the political agenda that resulted in the EU Biotechnology Directive. This significantly retarded research, development and applications of biological sciences. The directive has prohibited the use of genetically modified crops, effectively banned Horizon 2020 science funding from being spent on genetic research and has limited applications of developments in gene editing In the EU.

Germany’s Green Agenda has generated high energy costs that threaten its mercantilist model

Germany’s corporatist economic and social institutions do not welcome disruption and disruptive technologies are not exempted from this stasis. Germany has been slowly exploring and embracing the emergence of commuting technologies and the full ambit of the contemporary digital economy. However, the most significant example of Germany’s uncomfortable relationship is the decision by Angela Merkel’s government to end nuclear power in electricity power generation. After the nuclear accident at Fukushima in Japan, the German Government expedited its plans to phase out nuclear power generation. This made Germany further dependent on Russian gas. Part of the explanation for the decision to expedite the closure of Germany’s nuclear power plants was that the German media conflated the deaths and damage from the tsunami and earthquakes, with the specific and limited casualties of the nuclear accident itself. Germany’s energy agenda reflecting both its phasing out of nuclear power and its green agenda of decarbonisation, have resulted in German industry having some of the highest energy costs in the world. This compromises its traditional mercantilist model based on the competitiveness of its exports.

Modern German Economic Policy: A Weberian Ideal Type of what policy should have been Sixty years ago

Germany’s Ordoliberal economic institutions and the wider influence on Europe of the Germany culture of economic policy making when combined with the post-war German mercantilism and the tradition of Julius Tower public sector surpluses have created an economy well equipped to weather the challenges of fifty years ago. That is an analogue, manufacturing economy based around export-led growth and balance of payments surpluses; in a context where the legally framed culture of monetary and fiscal orthodoxy is that would be helpful in an financially unstable environment where there is high inflation, such as the 1970s. In short Germany and German influenced economic institutions in Europe, to paraphrase Thomas Mann, are well calibrated for a better yesterday.

Conclusions

Germany offers a rich and interesting economic history since the 1940s that is worth exploring. There are several inferences that can be taken from German economic history since 1945, and Germany's influence on European economic policy and institutions. Some of them are uncomfortable, particularly for political communities that have to manage unavoidable structural economic change.

Policies that work well in specific circumstances, such as those prevailing in West Germany between 1949 and 1965, may well not yield similarly successful results when things change. Framing economic and financial, monetary fiscal policy in brittle legal rules will mean that macro-economic policy is framed to conform to a legal rubric that will often not conform to challenges that would suggest different policies that would break the rules. This tends to lead to pro-cyclical policies asymmetric and unnecessarily suppress demand. Germany has framed domestic fiscal rules and contributed to EU wide fiscal rules that made it difficult for economies to respond to economic and geopolitical shocks. At their heart is a neuralgia about public debt that is misplaced. In Germany it aggravated the economic costs of managing the process of unification after 1990 and across Europe it has blunted the use of fiscal policy as a necessary tool in macroeconomic demand management. This has been an awkward problem for Germany and the EU after 2009 when monetary policy lost traction and a tool for stimulating economic activity.

The success of the West German Economic Miracle has meant that Germany has clung to its corporatist institutions long after both policy and institutions needed to change. Over much of the last forty years the principal efforts of German policy makers have gone into shoring up these policies and institutions to ensure that whatever happens disturbance to their functioning is minimised. This was the approach German policy makers took to preparations for the European Single Market after 1987, to German unification after 1990 and to the economic and financial crises arising from the banking crisis and Great Recession between 2007 and 20011. Resisting necessary and inevitable change makes an economy and a society serotic. It makes change when it comes harder to manage economically and more socially traumatic for people adversely affected by it.

The distinctive manner in which Germany managed the economic transition of the GDR’s socialist economy holds genuine lessons for other countries. Superficially the GDR was luck. It immediately inherited ready-made constitutional, legal and political institutions. It had immediate access to a functioning currency. And it had access to generous cash transfer payments from West German taxpayers. The eastern German lender should have experienced the easiest transmission of any of the former socialist economies in central and eastern europe. Yet as German economists such as Denis Snower and his colleagues at the Kiel institute have explained, the transfer payments themselves and the industrial subsidy aggravated the problems of transition. Regulation, social security benefits above realistic measures of workers’ productivity and investment into the public sector combined to crowd out the development of a functioning market private sector. The Kiel study corroborates interesting work done at Harvard Business School looking at the effect of pork barrel politics in the US Congress on the home states of the politicians, who brought the bacon home. Lauren Cohen, Joshua Coval and Christopher Mallory in 2011 published a paper Do Powerful Politicians Cause Corporate Downsizing? They found that exogenous increases in fiscal spending appear to dampen significantly corporate sector investment and employment.

A further inference that can be drawn from German economic history in the post-war years is the difficulty that communities have that undergo dramatic change in economic circumstances, in coming to terms with change. Germany’s eastern lender shares this trauma with communities in Britain and the USA. The communities that were the powerhouses of the British industrial revolution still mourn the losses of factories, mills and mines that took place fifty and ninety years ago. America’s ‘fly over country’, the effects of ‘Detroitification’ and the Rust Belt states have developed a distinct political sensibility that presented itself in presidential elections in 2016 and 2024. The difficulty for policy makers is that the normal tools of assistance - industrial subsidy, unemployment benefits, retraining, locating public sector agencies in affected regions appear to compound the economic difficulties of these communities rather than resolving them. The UK has one the longest experiences with such policies - right back to the Special Areas Acts of the 1930s. This reflects the fact that it was the first industrial economy and the first country to deindustrialise. Yet it has not been able to remedy either the economic performance of the communities involved nor assuage the psychological and social pathologies that have followed from radical necessary and unavoidable structural economic change.

Warwick Lightfoot

23 March 2025

Warwick Lightfoot is an economist and was Special Adviser to the Chancellor of the Exchequer between 1989 and 1992