Joseph Stiglitz’s policy advice is rooted in rose-tinted nostalgia about social democracy and the 20th century Keynesian welfare state consensus

The British NHS is not a gem, increased trade union power and returning to overreaching collectivism are not viable paths for modern economies.

The distinguished American economist Joseph Stiglitz is in the UK to promote his new book. He has graced the columns of the Financial Times and The Spectator with interviews and appeared on the BBC 1’s weekly Thursday Question Time current affairs show. Stiglitz has made a profound contribution to economics and the way that markets and prices work, exploring asymmetries of information, transaction costs, matters such as adverse selection and moral hazard that impede markets from working. Along with George Akerlof, this work done about fifty years ago, clarified our understanding of markets, prices and their limitations. In policy terms it has made Stiglitz a fan of public sector intervention, the replacement of markets by public policy programmes and a supporter of industrial strategies. In short, he is close to being the intellectual Godfather of the modern new Keynesian active state.

Stiglitz’s preferred rhetorical model in discussion and debate is to invoke Sweden and the Social Democrat consensus established in Scandinavia after the inter-war slump in the 1930s. It is a set of consistent collectivist reflexes – a large socialised public sector that has responsibility for a range of public services that extended far beyond any notion of public interest good or under provided merit good; entrenched trade union power across the economy; and high marginal tax rates to promote a political economy rooted in an egalitarian culture.

During his contribution to Question Time Stiglitz made a number of, from his perspective, helpful suggestions to improve the performance of the British economy and its public services. As well as the Swedish paradigm he invoked the National Health Service as a gem that he envied; and suggested that the British economy would perform much better if there was an increase in trade union power.

A feature of Stiglitz’s essays into political and economy and policy advice is often a superficial muddle of the historical episodes that he uses to illustrate the points he makes. They are marshalled in an amiable confection of partisan glosses and convenient straw man assertions that lack the care and rigour that distinguished the research of price formation and markets that he did earlier in his career. The political and policy persona of the contemporary Stiglitz is different from the academic scholar who has done so much to improve our understanding of prices. To be clear he is one the most pleasant people a person could engage in a polemic with about the big questions in modern economic policy and the role of the state. There is no personal malice or animosity in his conduct at all.

Sweden : A social democrat paradise lost

The Swedish model that Stiglitz speaks of broke down in the 1990s. This followed a long period of disappointing performance that had resulted in the Social Democrat Party losing office in 1975. By 1990 the shine had completely gone from the Swedish economy. There was rising structural unemployment, and despite heavy public spending on education and training there were few benefits from it given that high marginal tax rates and intrusive payroll social security taxes blunted the return to the human capital being accumulated, as the OECD noted in its country report that year in a document that could have been called Paradise Lost. Later in the 1990s a full-blown economic crisis, including banks collapsing, resulted in an extended period of structural reform. This included the partial dismantling of Sweden’s very high marginal taxes. As part of these changes Sweden abolished inheritance tax.

The British National Health Service – a gem or a modern government would not start from here?

Stiglitz presents policy advice and analysis as well as rhetoric that is rooted in nostalgia. The principal suggestions on Question Time were cherishing and spending more on the National Health Service and a revival of trade union power, along with a general approval for public intervention, industrial style strategies and spending on green investment to decarbonise the economy.

Yet the NHS gem that Stiglitz celebrates illustrates the way his nostalgia is misplaced. There have been huge increases in spending on health over the last-twenty-five years. It has consistently been a prioritised or protected programme. Yet the results of that spending in terms of patient satisfaction, choice, adaptation to new techniques of medicine and technology have been disappointing. This disappointment reflects a wider failure of the British public sector as a whole to demonstrate effective use of additional resources at the margin. Part of the explanation for this is to be found in poor public sector management of its employees in terms of basic employee attendance, sickness, and managing employee under performance. This can be found in the whole of the public sector, although it is less present in local authorities that have been subject to harder budget constraints, tough cash limited grant increases, caps on their Council Tax raising powers and periodic reorganisation, than in comparison with central government departments.

Initially the NHS performed well, particularly in relation to public health matters such as vaccination. Yet over time it has had progressive difficulty in meeting patient expectations, absorbing new technology, and introducing new working practices. Standards of nursing care, clinical diagnosis and the clinical management of morbidity can be egregiously disappointing. It is not just a question of waiting times and access to a General Practitioner, the NHS argot for family physician, it is the residual nature of the importance attached to the concerns of an individual patient and their family and carers that are its principal defect.

The National Health Service is the exemplar of a nexus of public sector management problems. A central part of it is the continuing presence of trade union power in UK public sector workplaces. A complex tradition of professional rent seeking was transferred to the NHS and then entrenched into the public sector when Aneurin Bevan, the Labour, Health Minister, who set it up, courted the British Medical Association in 1948. A distinctive feature of this rent seeking has been the creation of a public sector grade of specialist doctor ‘the consultant grade’ that is unusually well paid, in a public service setting. It enjoys wide professional and research privileges that only partially coincide with patient clinical care. It is part of a structure that has given institutional priority to acute hospital services over community services that address chronic conditions. Community medicine, community mental health services, the care of chronic conditions, such as the management of a diabetic ulcer and the services needed by older people, not least palliative care have been relatively neglected.

Trade union power is at the centre of the disappointing performance of the NHS and the wider British public sector

Trade union power, from the most sophisticated professional rent seeking at the top of the medical profession down to the staff contributing at the bottom of NHS’s clinical and professional hierarchies, is entrenched. Neither senior specialist hospital consultant doctors, nor managers, feel confident about identifying poor work even when it has involved the safety of patients. There is an omerta on staff complaints from doctors who call out these defects, that systematically results in the cover up of poor clinical management. Too often when problems are present people model themselves on Admiral Lord Nelson, placing a telescope to a blind eye. In one notorious example that eventually led to the murder conviction of a paediatric nurse, the concerns of colleagues including senior clinicians were overlooked and subject to complaint and professional criticism before action was taken.

This poor management is replicated week in, week out in hospitals throughout the country. There are senior consultants who hire in expensive agency nursing cover, because the nurses on duty that night, on an acute psychiatry unit are deemed by them to be clinically unsafe. A gynaecologist who gives written and verbal instructions to a midwife and nurses about a patient's care, that are not carried out and thereby putting the patient’s life at risk, is disciplined for expressing surprise and concern about the failure to carry out the clinical instructions given. A surgeon observes that on average over a twenty-year period in the operating theatres apart from the doctors, staff absence runs consistently at around 40 per cent.

The nursing strikes, the industrial action of the junior doctors over their pay claim and the action of the senior hospital consultants in relation to their contracts are merely the most vivid expression of trade union power in the health service. The greatest impact of this power is in the way it has emasculated normal management of staff conduct, competence and efficiency. Over the last twenty-five years the motto of the National Health Service could have been ‘I am sorry you have had an unfortunate experience’.

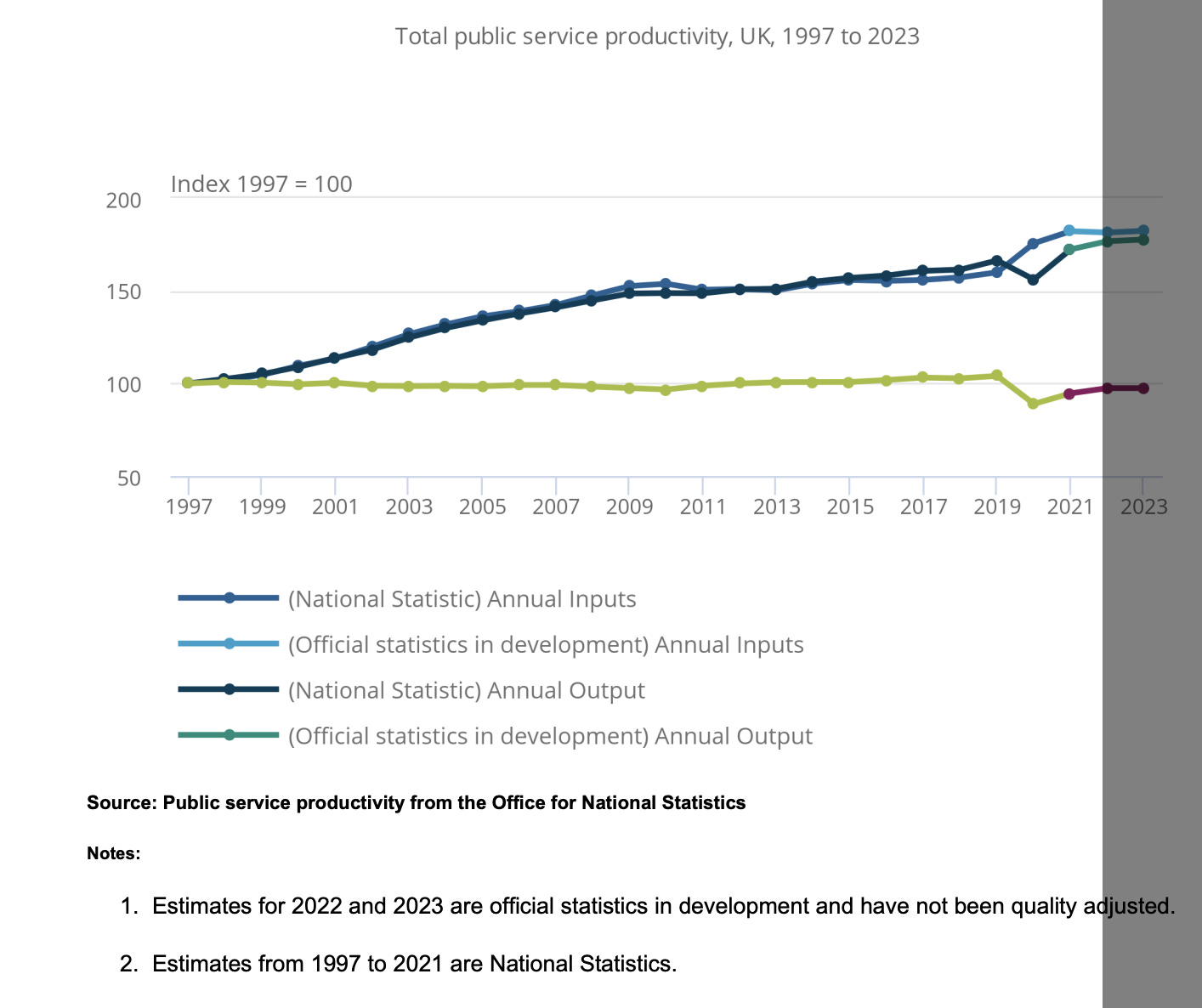

Measuring public sector productivity in UK

As a matter of serendipity, the morning after Joseph Stiglitz’s encomia to the NHS gem and the benign benefits of trade union power, the ONS published a statistical bulletin on UK public sector productivity. It showed that after a recovery in productivity recorded in the public sector following covid, productivity had fallen. The ONS report stated ‘As seen in our previous public service productivity bulletin, public service productivity levels have remained relatively stable since Quarter 2 (April to June) 2021. Over this period, inputs grew by 3.2 per cent, while output grew by 2.8 per cent, leading to a fall in productivity of 0.4 per cent.’

Yet this is the least of the problems recorded in the bulletin. It is the sluggish growth of public sector productivity between 1997 and 2019 that is the devastating contradiction to Joseph Stiglitz’s amiable confidence in public expenditure and trade union power.

The ONS reported ‘The trajectory of total public service productivity over the period 1997 to 2020 shows a shallow decline to 2010, followed by a steady increase to 2019; 2020 saw a large decline in measured productivity during the coronavirus pandemic. The contributors to productivity differ during these periods. While both output and input growth were positive throughout the period, annual growth of both output and input in 1997 to 2010 far exceeded that of 2010 to 2019. Input growth exceeded output growth pre-2010, and output growth exceeded input growth post-2010.’ Now it should be noted that within the public sector between 1997 and 2019 health performed relatively better than other parts of the public sector, such as social services, in terms of recorded output growth’.

The statisticians at the UK’s ONS have energetically tried to directly measure the output and productivity of the public sector since the introduction of the New European System of National Accounts was introduced in 1998. This applied UN agreed conventions for measuring GDP in market economies. When the first results of this work became available in the early 2000s it exposed the disappointing productivity performance of the public sector. These disappointing results and their implications for effectiveness of public spending were greeted with disbelief, by Labour ministers such as the Chancellor of the Exchequer Gordon Brown. He was, moreover, irritated by the effective use that Michael Howard, the Conservative Shadow Chancellor, made out of the embarrassing statistics. This resulted in the Atkinson inquiry being set up to investigate what had gone wrong with the attempts at measuring public sector productivity. Sir Anthony Atkinson, the Warden of Nuffield College, Oxford was the doyenne of economists who has studied inequality and the dispersion of income and wealth. He had also collaborated with Joseph Stiglitz in a book in 1981. At the end of Sir Anthony’s investigation little changed in the ONS methodology that would alter the broad picture of increased spending unmatched by significant measured increased growth in public service productivity. The ONS is under continuous pressure to produce statistics that would offer a better gloss on this awkward artefact. It is not an accident that some of the latest data is published with the sobriquet ‘experimental’. This pressure comes from people connected to the public sector, such as my old friend Dame Moira Gibb, a distinguished former director of social services, former President of the National Association of Directors of Social Services, and a former local authority chief executive, who later served as a member of the ONS board. Moira certainly felt that the statisticians were not able to capture the increased output of marginal expenditure in full and more work should be done to do this.

Britain pioneered the welfare state and Keynesian economics

Britain in the middle of the 20th century was in many respects the pioneer of what became known as the Keynesian welfare state model. In the 1940s Winston Churchill’s wartime coalition government adopted Keynesian demand management to secure full employment, in Sir Kingsley Wood’s 1941 Budget Statement; accepted the Beveridge Report on social insurance; and in the 1944 Employment White Paper, with its drafting guided by Lord Keynes, the government committed itself to maintaining full employment. It was the Archbishop of Canterbury William Temple, who coined the phrase ‘welfare state’ and Winston Churchill who vividly described it as taking care of the welfare of the citizen from the ‘cradle to the grave’ in a BBC broadcast on the Beveridge Report in March 1943. The 1944 Butler Education Act gave all children the opportunity of having a full secondary education and equality of opportunity in going to university. Clement Attlee’s Labour Government between 1945 and 1951 nationalised the Bank of England, coal, gas, electricity, railways and steel and set up the National Health Service that was itself the nationalisation of municipal and independent great charity hospitals.

Yet within twenty years of Clement Attlee taking power in 1945, there was serious disappointment with the results of the welfare state. At the height of post World War 2 mass affluence, entrenched poverty remained. Squalor, poverty and want had not been eliminated in the manner expected by Lord Beveridge. Complex social pathologies remained and appeared immune from the intrusion of the welfare state. In the early 1960s this was exemplified by the film Cathy Come Home. In the 1960s an ambitious and optimistic cabinet of Labour ministers led by Harold Wilson were confident that they could remedy these disappointments. Anthony Crosland as Secretary of State for Education embarked on the comprehensive revolution that dismantled the 1944 Education Act tripartite structure of grammar, technical and secondary modern schools and expanded higher education by establishing the Polytechnics, in addition to the newly expanded university system following the implementation of Lord Robins report on higher education.

Crosland’s ideological enemy in the Labour Party’s debates in relation to the revisionist arguments about the future of socialism and the role of economic planning that, he had initiated in the 1950s, was Richard Crossman. As minister for Housing and Local Government and as Secretary of State for Health and Social Services, Crossman expanded the welfare state in relation to housing, support for low income households and personal social services, essentially identifying lacuna in things such as the National Assistance Act 1948 and filling them. This involved an expansion of an already comprehensive welfare state, implementing the Seebohm Report on social services and spending more on them. A good example was the introduction of Supplementary Benefit to fill in the gaps in the 1949 National Assistance Act.

Complex social pathologies that appear immune to the actions of the welfare state

Yet the results remained disappointing. Both Richard Crossman and his Conservative successor, as Social Services Secretary, Sir Keith Joseph explored the concept of cycles of intergenerational deprivation that were not easily tractable, however ambitious the public policy remedy was. The columns of the New Society – the social sciences sister magazine to the New Scientist and The Listener in the 1960s and 1970s - were filled with the disappointment and anxiety of campaigners, economists and sociologists, such as Richard Titmuss, Brian Abel Smith, Peter Townsend and Frank Field exploring the complex pathologies that that appeared immune to public policy initiatives, however energetic. The Finer Report on One-Parent Families, which was published in 1974 was set up by Richard Crossman partly in response to these anxieties.

Means testing, tapers and marginal rates of withdrawal

In the late 1970s, 1980s and 1990s there was increasing attention to the manner in which transfer payments and means tested or targeted benefits may create perverse incentives that aggravate these complex pathologies and result in detachment from the labour market, in particular. This was a matter that greatly concerned Frank Field who later became minister for social security in 1997. It was also a great concern to Lord Young who served as Mrs Thatcher’s Secretary of state for Employment and Secretary of State for Trade and Industry, engaging in a protracted ministerial correspondence with the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Nigel Lawson over the issues involved in the tapers applied to the new system of Family Credit in 1988 that had expanded the scope of Family Income Supplement (FIS) introduced in the early 1970s.

Disappointing results from successive episodes of increased public spending

Three distinct episodes of increased public spending directed at addressing these challenges can be identified: Harold Wilson’s Labour Government between 1964 and 1970; large discretionary increases in general government expenditure between 1986 and 1993, under Mrs Thatcher and John Major; and between 1997 and 2010. Gordon Brown’s New Labour energetically tested the proposition that there was nothing much wrong with public services that proper funding would not put right.

Once a state is spending over two fifths of its national income on public services it is not clear how they can be improved or in the rhetoric of British politicians since the millennium, ‘transformed’ by spending more money. Vito Tanzi the former head of the IMF’s fiscal division and his IMF colleague Ludger Schuknecht, explored this in their book Public Expenditure in the 20th Century a Global Perspective. They catalogued big increases in public spending in advanced economies in the middle of the 20th century – roughly from the 1940s to the mid-1960s – that brought about big improvements in health, education and general well-being. Moreover, they did not appear to impede the steady evolution of the productive capacity of market economies, growth was good. Indeed, this showed that a properly framed and realistically focused welfare state could contribute to a market economy performing better. Yet the large increases in the ratio of public expenditure across the OECD, from the late 1960s and in the 1970s and 1980s, did not yield comparable observable benefits and began to appear to impede the functioning of private markets.

There are two dimensions to this discussion. The first relates to the micro-economic performance of the economic services such as health, personal social services or education, their observed efficiency and capacity to meet their objectives. The second involves a broader macro-economic dimension where public expenditure and the taxation that goes with it changes incentives, significantly modifies returns to human and physical capital and creates structural consequences for the performance of labour and product markets. This is where a series of awkward propositions begin to be observed.

They include the deadweight costs of public expenditure over and above their direct financial or cash cost that arise from the manner in which public expenditure modifies and distorts market behaviour; the effects of the double taxation of saving under income taxes that being a heavier average burden in economies where the state absorbs over 40 percent of output; the aggravated deadweight costs of payroll social security taxes in relation to the supply and demand for labour; the effects that the aggravated double taxation of dividends have on company balance sheets promoting the use of debt and resulting in the thin capitalisation of businesses. Many of these malign consequences of public intervention become evident as public expenditure increases and the tax burden needed to finance it becomes heavier. In short, a theoretical proposition, such as the double taxation of savings income when there is an income tax, first identified by John Stuart Mill in his book Principles of Political Economy in 1846, looked remote in 1900 when public expenditure accounted for around 12 percent of GDP. Yet it becomes a practical problem when over two fifths of national income is accounted for by public spending and when there are high marginal income tax rates and a tax burden that descends down the earnings distribution.

In an economy where the state allocates over 40 per cent of national income, such as the UK, households will both pay taxes and be in receipt of transfer payments, such as child benefit, pensions and benefits in kind such as health care and the provision of goods such as public supported arts and cultural events. As spending rises it can only be financed by a tax system that descends down the distribution of earnings. As social policy becomes more ambitious in modifying the distribution of market incomes, transfer payments have to become more targeted, in order to be affordable in terms of overall public expenditure cost. More means testing, more withdrawal rates and more tapers are applied creating what are in effect very high marginal tax rates that appear across the earnings distribution. Households across the earnings distribution simultaneously become subject to high marginal taxation and are entitled to means tested benefits.

The result is an awkward fiscal churn, with complex and malign implications for incentives to work, save and invest. An egalitarian impulse to withdraw benefits that are universal in character so that higher income households do not benefit from a policy to support families with children or university and college education, creates aggravated marginal tax rates higher up in the middle of the earning distribution, although a long way below the very top, as benefits are withdrawn at very high marginal rates.

Denis Healey’s 1976 Public Expenditure White Paper: the end of the post war Keynesian consensus

In February 1976 Denis Healey published a white paper on public expenditure that effectively broke with the post-war consensus on Keynesian demand management. In the trough of a recession, it set out plans to cut spending and borrowing as unemployment rose. It also lucidly explored Britain’s structural public expenditure problem. Central problems of a high spending welfare state were fully exposed in the UK in the mid-1970s. The 1976 Public Expenditure White Paper captured concisely what is still the central contemporary challenge of the modern rich comfortable democracies in Europe and North America:

‘In managing public expenditure two problems stand out. The first has been with us for many years. Popular expectations for improved public services and welfare programmes have not been matched by the growth in output - or by willingness to forgo improvements in private living standards in favour of those programmes. The oil crisis intensified this gap between expectations and available resources. The second problem is that cost inflation, which has become acute in the last few years, has added an extra dimension of difficulty.

In the last three years public expansion has grown by nearly 20 per cent in volume, while output has risen by less than 2 per cent. The ratio of public expenditure to gross domestic product has risen from 50 per cent to 60 per cent. Fifteen years ago it was 42 per cent. The tax burden has also greatly increased. In 1975-76 a married man on average earnings is paying about a quarter of his earnings in income tax, compared with the tenth in 1960-61. At two-thirds of average earnings, he is paying about a fifth compared with less than a twentieth.

Tax thresholds have fallen sharply in relation to average earnings, and people are being drawn into tax at income levels which are below social security benefit levels. The increase in the tax burden has fallen heavily on low wage earners. Those earning less than the average contribute over a quarter of the income tax yield. This cannot be made good by simply increasing the burden at the top: if no tax payer was left with more than £5000 per annum after tax, this would increase the yield by only around 60 per cent’.

While the precise numbers are different not least because of differences in data and the presentation of the ratio of general government expenditure to GDP, the broad thrust of the analysis that Denis Healey laid out on page one of the White Paper still holds.

Asser Lindbeck and the crisis of Swedish social democracy

These problems arising from the effects of taxation on incentives, as well as the impact of benefits administration and trade union power became increasingly clear in Sweden in the 1970s. A Swedish economist Asser Lindbeck, who chaired the Nobel economics committee, explored how these effects eroded social norms around personal responsibility and work ethics. Lindbeck also used Swedish experience to construct the highly influential insider-outsider analytical model of an increasingly privileged group of workers occupying well paid protected jobs, while it becomes progressively difficult for people who are detached from the labour market to find comparable protected and rewarded employment. This analysis played an important part in the OECD’s work on structural labour market problems in advanced economies.

In the 1970s and 1980s the Swedish economy suffered from diminishing international competitiveness, capital flight and Social Democrat and non-socialist governments. The 1980s and 1990s had to respond with cuts in public spending, monetary control, deregulation, and structural changes to return the economy to the usual norms and disciplines of market economies. Ratios of public spending and taxation to GDP remain higher in Sweden than in North America, but Sweden still presents with difficult social pathologies in the same way as other advanced economies with developed welfare states. Not least in relation to the integration of minority migrant communities. Joseph Stiglitz and many left-wing and liberal social scientists offer a superficial gloss on Sweden, often overlooking the public policy they share in common, as well as many shared social pathologies.

America has its own exceptionally difficult public sector costs

In many respects these features are evident in the US where a potent combination of federal and state government initiatives interact to create a Manhattan skyline of marginal tax rates across the earnings distribution. Benefits phase in and phase out. There is the Earned Income Tax Credit, assistance college education, and the means test applied for access to Medicaid. The Affordable Health Care Act passed in 2009 expanded the number of households in receipt of Medicaid benefits that are withdrawn as income rises. The legislation introduced a further subsidy for the purchase of private health insurance that is tapered away as income goes up. The American economist Laurence Kotlikoff has explored and attempted to model the complex interaction of these federal programmes with state spending and state and federal taxation and their impact on incentives to work and save.

America - more in common with European welfare spending than many people think

Joseph Stiglitz often explains how he would like the US to be more European. Yet when federal, state and local spending are fully scored as part of general government expenditure within national income and a necessary adjustment is made for large tax expenditures supporting private employer provided health insurance, the ratios of overall public intervention between the US and Europe are not dissimilar. Some things such as the basic state pension Social Security are more generous, for example, than the UK. When all public spending on healthcare is scored – Medicaid, Medicare, veterans, federal government employees, state and local government employees and the health insurance expenditures provided by the tax system, US public sector spending on health is not much different from UK spending on the NHS as a ratio of GDP.

The big difference between the US and Europe and most advanced economies in the OECD, such as Australia and Canada, is the reluctance of the US to use broadly neutral comprehensive expenditure taxes such as VAT. Economists generally regard neutral expenditure taxes as the most efficient means of raising tax revenue with the least deadweight costs. The US has large lumpy health and welfare spending programmes that are poorly targeted and expensively delivered, particularly health programmes that use private insurance and health care markets.

What Joseph Stiglitz could do to educate his British hosts

Joseph Stiglitz is a stimulating visitor, and we are fortunate to be able to welcome him and enjoy his presence and interest. I last saw him in 2015 when he was promoting a book of collected articles The Great Divide at the Dartington Literary Festival Ways with Words in Devon. He is generous, good humoured and amiable. However, he should not be given a free pass on friendly interrogation of his ideas and his ready and fluent expression of policy which comes from a nostalgic hinterland that too often resiles from recognising the awkward deadweight costs of public expenditure, taxation and regulation, and too often suggests that people who have reservations about further increases in public expenditure or a revival of trade union power, simply want markets to do everything and do not recognise the limits on both markets and the information that prices can yield in markets for things such as insurance.

Where Joseph Stiglitz should make more efforts on his visits to Britain, is in educating policy makers about the concepts – adverse selection, asymmetries of information and moral hazard that he has done so much to develop. These are the things that prevent private insurance markets working at a reasonable cost in areas such as social care. England has a health service where all medical care is free and provided by collectively raised taxation whether serious or trivial, expensive or cheap, whereas complex, serious and expensive social care is subject to a draconian charging regime until a household’s assets are exhausted and places it in the hands of the social security system. They are central to the case made by the Sutherland Royal Commission Report on funding long-term social care for tax funded care in 1999 and are at the heart of the House of Lords Economic Affairs Committee’s conclusions on social care funding in 2019.

This is the exercise in economic education that Joseph Stiglitz should concentrate on for the benefit of his British hosts. In the meantime, British policy makers would be better employed fully acquainting themselves with the costs of public expenditure, the fact that those costs exceed the cash cost because of the deadweight costs and distortion of spending and its financing involved and identifying the marginal returns to increased spending to ensure that they exceed the costs. There is one observation Joseph Stiglitz is right to emphasise, as he did in his interview with Kate Andrews in The Spectator. This is that governments should not be afraid of using their balance sheets to borrow. Public debt is a shock absorber and an enabler. The key question in public finance is how much is being spent, its deadweight cost and its return - how it is financed between taxation and borrowing is a second order question. These are difficult questions that involve real resource costs, opportunity cost and constraints that Joseph Stiglitz in his policy advice is reticent about exploring.

Warwick Lightfoot

5 May 2024

Warwick Lightfoot is an economist who served as Special Adviser to the Chancellor of the Exchequer between 1989 and and 1992.