Jackson Hole Economic Policy Symposium: Structural Shifts in the Global Economy August 2023

Jackson Hole Central Bank Meeting, what it is about, 2 per cent inflation reaffirmed, US Treasury Market illiquidity, learning to live with government debt.

The Economic Symposium hosted by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas at Jackson Hole in Wyoming annually at the end of August, is one of the longest-standing central banking conferences in the world. The event brings together economists, financial market participants, academics, U.S. government representatives, and news media to discuss long-term policy issues of mutual concern. It has been going since 1978 and had 370 participants from 70 countries and published 150 papers. Normally around 170 people gather. The group is principally composed of central bankers, mainly from the US Federal Reserve system, with a significant group of academic economists as well as smaller groups of participants from the media, financial market practitioners and government.

At international monetary meetings the focus is on what the US will or not be doing

Most of the attention is focused on contributions made by the Chair of the US Federal Reserve and there tends to be less attention paid to the contributions of other central bank governors such as the head of the ECB or the governor of the Bank of Japan, who attended this year. As a rule of thumb at all big international economic and financial gatherings such as this and the IMF World Bank annual meeting, the focus is on the US Treasury and the Federal Reserve. Individual national media will report what their own British, French, or Japanese central bank governor or finance minister may or may not be saying or doing, but there is usually little international interest in them. The focus is on the US participants. Jackson Hole tends to conform to this general rule.

There are a series of academic papers presented and published each year. The paper is usually complemented by a panel discussion. The participants on those panels often publish short comment notes as handouts. These increasingly take the form of a few charts and statistics used to illustrate their commentary and often take a PowerPoint form. In previous years, especially during the Covid public health emergency, there was much more video footage of its proceedings. So far, for the August 2023 meeting the only video available of the presentations is for Jerome Powell the Federal Reserve Chair’s speech.

Almost all the reporting and media focus is on the Federal Reserve Chair’s presentation and what it means for US interest rates and by extension international liquidity. There are usually several interesting academic papers that deserve wider and fuller interest.

An analysis of the liquidity challenges in the US Treasury Market

This year these include an important discussion of liquidity in the US Treasury market and its wider functioning, by Darrell Duffie a professor of economics at Stanford University, Structural Changes in Financial Markets and the Conduct of Monetary Public. The broad gist of the analysis is that since the changes to US banking and international banking rules in response to the financial crisis in 2008, banks have to keep more capital on their balance sheets. This means they are more careful how they use the capital available to them to ensure that they allocate it to their most profitable activities. Making it available to their primary dealing departments and contributing to liquidity in the interdealer market in US Treasury securities is costly and has relatively low returns. This has made the US Treasury market less liquid and a less efficient method of price discovery.

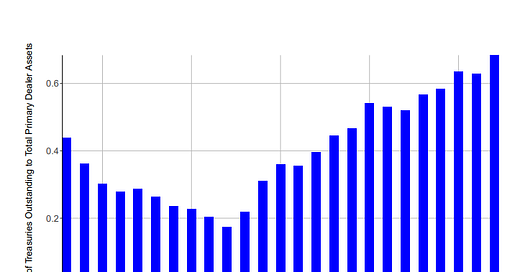

The ratio of US Treasury securities outstanding to primary dealer assets over the period 1998-2022. Data: The Federal Reserve and company filings. Assets are measured at the holding company level.

During episodes of interest rate and bond price volatile as the risks increase the appetite to allocate scarce capital to a higher risk business relative to its returns diminishes. This contributed to the US Treasury market liquidity problem in the Spring of 2020. One solution is for central banks to support market liquidity with enhanced public sector clearing arrangements. It is worth noting that these problems are not confined to the US, they were exposed inter alia in the UK gilt and indexed linked gilt market in September 2022. It required Bank of England intervention to stabilise the market. That intervention did not prevent bond yields eventually rising as they needed to reflect a necessary further tightening in domestic UK monetary policy to reduce UK inflation. Dufield’s suggestion of public supported clearing has been explored by Miachel Flemming, an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, who has studied the structure of the US Treasury Market for many years. He compared liquidity in the present market with that of the liquidity that would be available in a supported market with some counter factual modelling.

A realistic assessment of living with the constraints of high public sector debt – there may be a silver lining to the cloud

The substantial paper Living with High Public Debt presented by Serkan Arslanalp and Barry Eichengreen will invite careful consideration. The gravamen of their argument is that official economics, the stuff produced by central banks, finance ministries, the EU Commission and international bodies, such as the IMF and OECD is that public debt is at unprecedented high in relation to national income in peace time and needs to be reduced. Serkan Arslanalp and Barry Eichengreen’s point is that this will not happen because it would require governments to run primary budget surpluses that will not materialise. Instead, governments will have to learn to live with high debt as a constraint. They however make an important observation: ‘A silver lining of the additional stock of government debt in the hands of the public may be to relieve the global safe-asset shortage that has contributed to high prices and low yields on advanced-country sovereign bonds in recent years. Additional debt issuance may attenuate this problem and also address its negative consequences, including low interest rates on safe assets, limited scope for active use of conventional monetary policy in downturns, and the danger of becoming stuck at the zero lower bound’. The world economy in the 21 century would have functioned a great deal better if there had been a more normal structure of interest rates and higher bond yields where credit was realistically and there was less scope for asset price bubbles. Arslanalp and Eichengreen argue that unproductive areas of public spending and transfer payments will have to be looked at in this constrained fiscal environment.

Science and research may be merit goods but there are structural constraints on economic growth

Other written contributions that will be worth thinking about are the handouts to support the panel discussion on Structural Constraints on Growth. These include the handouts of Charles Jones and Chad Syverson.

From Charles Jones Handout at the August 2023 Jackson Hole Economic Symposium

Policy makers and commentators invoke investment in new technology and increased spending on science and research as a painless elixir that will generate economic growth in advanced economies. There are many good reasons to spend on science as a merit good. Yet there is unlikely to be a mechanical or reliable connection between doing so and a return to the growth that advanced economies enjoyed in the second half of the 20th century.

Jay Powell: the Big Jackson Hole Speech – got to get inflation down to 2 per cent

Jay Powell, the Federal Reserve Board Chair, captured the limelight. His message was clear: the Federal Reserve was determined to get inflation down to 2 per cent as measured by the Personal Consumption Expenditure Index. He recognised that this would involve below trend growth, and that the US economy was exhibiting that now. He explained that the effect of monetary tightening and its lags were uncertain and the Federal Reserve would have to be careful not to damage the economy unnecessarily. It is plainly good news Mr Powell is committed to getting inflation down and recognises that there is an economic price to be paid to do it.

Yet the havering around not knowing what the neutral rate of interest is and trying to judge policy optimally created the sort of indecision that has created the general inflation present in the American economy and has amplified the consequences of the various relative price effects that have put up inflation arising from Covid , disruption of trade and output and changed patterns of spending – more purchases of goods and less spending on services in a period of intensive expansion of demand from both fiscal and monetary policy between 2020 and 2021. There are four direct questions where guidance from the Federal Reserve Chair would be helpful; can inflation be bought down without positive real interest rates; how realistic is it to accomplish disinflation without a short term fall in output that goes beyond growth below its trend rate, particularly in an environment lower trend rates of economic growth; what is the Federal Reserve’s understanding of the monetary mission mechanism in the modern economy, and how should monetary policy be framed to prevent a future failure of monetary and inflation policy. For more than twenty-five years the Federal Reserve has been opaque if not straightforwardly cagey about the question of monetary conditions, the transmission mechanism, relying on its own announcements to anchor expectations without any explanation of the causation involved.

What does Europe think?

Christine Lagarde’s, the President of the ECB, contribution is worth taking note of. Her officials furnished her with some interesting observations. Before exploring them, it is worth noting that she says that her central bank is committed to getting inflation back to 2 per cent. This is welcome given the amount of discussion among academic economists and some financial market practitioners about the desirability of abandoning a 2 per cent inflation objective and replacing it with something closer to 4 per cent.

Noticing that the world has changed is a good start

The first interesting observation in her speech was ‘Since we may be entering an age of shifts in economic relationships and breaks in established regularities. For policymakers with a stability mandate, this poses a significant challenge. We rely on past regularities to understand the distribution of shocks we are likely to face, how they will transmit through the economy, and how policies can best respond to them. But if we are in a new age, past regularities may no longer be a good guide for how the economy works’. The structure of advanced economies has changed radically over the last twenty-five years – less manufacturing, much bigger service sectors, a large digital and intangible dimension to economic activity and huge changes in the conventions used to construct national accounts in the EU as part of the New European System of National Accounts. These changes made estimating and forecasting the economy much more difficult before there were any global supply shocks.

The second is that in ‘the pre-pandemic world, we typically thought of the economy as advancing along a steadily expanding path of potential output, with fluctuations mainly being driven by swings in private demand. But this may no longer be an appropriate model’. Monetary policy must respond realistically to both demand and the productive capacity available. There are many things that can reduce potential supply and can constrain the supply performance of the economy structurally, such as damaged work incentives, and crowding out arising from an expanding public sector.

She also notes that ‘we are likely to experience more shocks emanating from the supply side itself’, and ‘importantly, we are likely to see a phase of frontloaded investment that is largely insensitive to the business cycle – both because the investment needs we face are pressing, and because the public sector will be central in bringing them about’. These will potentially result in larger relative price effects and will require a determined non-accommodating monetary policy response to prevent inflation.

Whether the ECB has the willpower to deliver on 2 per cent inflation is a question invited by Christine Lagarde’s qualification ‘over the medium term’

So, while it is welcome that Christine Lagarde says ‘we must and we will keep inflation at 2 per cent,’ ‘over the medium term’ appears a qualification that invites a less than effective policy response as she and her colleagues make their ‘future decisions contingent on three criteria: the inflation outlook, the dynamics of underlying inflation and the strength of monetary policy transmission’. In this context ‘underlying inflation’ in the words of a modern central banker’, is a bit like balancing the budget over the economic cycle and a finance minister helpfully saying, it may be a very long economic cycle.

Christine Lagarde emphasises something that is still overlooked in economic policy discussion: future much higher costs of defence spending in advanced economies

A matter that has not yet been fully taken on board in economic discussion was interestingly mentioned by Christine Lagarde in conjunction with a point she made on the future cost of €600 billion of green investment. ‘The new international landscape will require a significant increase in defence spending, too: in the EU, around €60 billion will be required annually to meet the NATO military expenditure target of 2 per cent of GDP.’ The changed geopolitical position arising from the deterioration in relations between NATO and the Russian Federation, the strategic partnership between Russian and China and China’s growing military and political assertion not just in the South China Sea, will mean much greater spending by advanced economies. 2 per cent of GDP is likely to be much less than the start of it. In 1979 the NATO defence spending target was 3 per cent of GDP. During many years of the Cold War defence spending ratios in countries such as the UK and US was significantly higher.

To return to 2 per cent inflation central banks have more monetary tightening to undertake

In terms of monetary policy, perhaps the most interesting and pertinent comment made at Jackson Hole was made by Susan Collins, the President of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston in an interview with the Financial Times on 24 August 2023. She explained that she was surprised by the resilience of the economy, the tightness of the labour market and the continuing strength of consumer spending. Collins told the FT that ‘I am not yet seeing the slowing that I think is going to be part of what we need for that sustainable trajectory to get back to 2 per cent [inflation] in a reasonable amount of time …that resilience really does suggest we may have more to do’.

Warwick Lightfoot

27 August 2023

Warwick Lightfoot is an economist who was Special Adviser to the Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1989 to 1992.