Industrial Revolution, inventing Political Economy, relative 20th century British economic decline and the creation of a modern post-industrial economy

It made Victorian Britain egregiously rich, but its costs stimulated a political antithesis that provoked a generation of socialist policies and a decline that fostered a culture of economic nostalgia

The main feature of Victorian Britain was prosperity taken to new heights by technological innovation. Britain became rich compared to all other major countries as a result and its rapid visible technological advance. In the 18th century Britain had been a prosperous commercial society, but the Industrial Revolution transformed its relative productive potential. Nicholas Crafts in an article published in the Journal of Economic Perspectives Forging Ahead and Falling Behind: The Rise and Relative Decline of the First Industrial Nation in 1998 laid the stylised facts out clearly:

‘Between 1780 and 1870, Britain’s real GDP/person almost doubled to $3263, leaving the United Kingdom about 20 percent ahead of the Netherlands (previously the leading European country), 70 percent ahead of both France and Germany, and about a third higher than the United States (Maddison, 1995). By 1870, the proportion of Britain’s labor force employed in agriculture had halved from 1780 to 22.7 percent, a figure not reached in the United States until the 1920s or in Germany until 1950. Whereas employment in manufacturing was around one-third of the U.K. labor force in 1870, in the United States it was only about one-sixth’.

This unusual relative position was unlikely to last, because there would be ample scope for the diffusion of technology and for other countries to catch up. Moreover, the technologies that made Britain rich after 1790 would have the potential in different circumstances to make other economics even richer.

Technology transformed output and productivity after 1780

The relative prosperity came from the agricultural and industrial revolutions in the 18th century. These enabled a huge increase in productivity and output. The emergence of new production that turned on specific novel technologies that worked in particular British geographical locations was partly serendipity. Textiles benefited from new looms that worked cloth well in a damp environment that was readily available in Lancashire, coal could be used in parts of Scoltland and the North East of England for iron and then steel in ship building.

Welsh Steel Furnaces

The steam engine that came first in 1712 in Cornwall could take advantage of coal as uses for the application of steam power emerged. The role of steam was then transformed by the perfection of the steam turbine in the 1880s. While the understanding of the practical uses of electrical current would futher transform application of steam power through the generation of electricity. Steam powered by more efficient turbines generated electricity and a new technology emerged that transformed productivity again between the 1920s and 1950s.

Social and legal institutions permitted Britain to take advantage of new technologies

The use and application of these new technologies was made possible by a relatively open and free society that permitted scientific inquiry and had a framework of commercial law that permitted the ownership of property, the creation and transfer of property rights. By the middle of the 18the century England had created a distinctive vibrant commercial society. Much of this legal framework was developed to manage property rights in relation to the ownership of land and then trade involving shipping.

After 1690 this emerging commercial society took on a financial dimension. The creation of funded public debt and the Bank of England to issue the debt and keep a register of its ownership transformed British finance. The new issues created to finance the wars with France were modelled on the Dutch example, rather as the reform of the London Stock Exchange and Gilt Market were later to be reformed on the US model at the time of BIg Bang in the mid-1980s. This created new opportunities both for trade and for much wider and more convenient holding of wealth. It resulted in a secondary market in government debt. This created opportunities for financial speculation, investment and the development of new financial products such as annuities. These widened the opportunities to save and invest. Parents could provide capital for children that was more easily divisible. This was particularly helpful in relation to the support of women - widows and unmarried daughters. It was also important for charities. This can still be seen in the encomia on the walls of parish churches recording the generosity of parishioners who paid to support the local poor by investing in government funds, stocks and Consols for the purpose. The expression 'being in Funds' gained currency as a vivid term for having plenty of money. The significance of this financial transformation was explored in Peter Dickson's bookThe Financial Revolution in England : A Study in the Development of Public Credit, 1688-1756.

In the 19th century Britain’s capital markets developed further. The need to mobilise large amounts of capital for big and complex industrial enterprises, not least for railways, resulted in the modern joint stock company and the markets that go with it The Joint Stock Companies Act 1844 facilitated procedures that enabled joint stock companies to be created by routine registration. The Limited Liability Act 1855 protected the liabilities of shareholders to the money they subscribed and the Joint Stock Companies Act in 1856 laid the basis for modern company The London Stock law.

Huge economic change provoked great social and political change and emergence of a bourgeois society where power became vested in capital

The social, political, legal and financial institutions that Britain had in the 18th century enabled its economic agents to make good use of the new technologies that swiftly emerged after around 1780. New technologies created new markets and enabled rapid accumulations of wealth arising from the output of mills and mines. This new wealth disrupted previous social and political relationships. Wealth arising from the industrial revolution soon eclipsed that based on land. Much of 19th century English literature written by the likes of Thackery, Geroge Eliot, Dickens and Trollope was the exploration of the social changes brought about by this changed industrial landscape. The relative importance of aristocratic wealth based on the possession of inherited land ownership atrophied, eclipsed by new industrial fortunes.

Uncomfortable social change cruel social costs

Rapid economic change came with uncomfortable social change and disruption. People feared new technology. An anxiety that was encapsulated in the debate about the 'Machinery Question.' The emergence of manufacturing industries created huge opportunities for increased output and productivity. When combined with innovation in banking and capital markets, the new industries amplified the economic cycles that had traditionally been associated with agricultural harvests. Opportunities for rapid capital accumulation were matched by equally arresting episodes of financial destruction. Karl Marx as a financial journalist was an acute observer of these changes - the creation of a bourgeois society where economic power was detached from land and inherited social status, the uncomfortable social costs for people caught up in the wrong end of this and the dramatic trade cycles that formed part of the rhythm of his new process of capital accumulation. The French sociologist Emile Durkheim perhaps best captured the broader impact of these changes and social costs with the concept of 'anomie'. People worked in new urban environments that were detached from traditional experience of custom and community. The result was bitter alienation.

The Political Economy provoked by the stresses of capitalist accumulation

There were clear social costs attached to the industrial society and the cities that emerged in the 19th century. While the great names of classical political economy Adam Smith, David Ricardomn and John Stuart Mill analysed and described market economies powered spontaneous self interest that powered commercial affluence, the social costs of the industrial revolution stimulated a powerful critique of capitalism's social and economic costs.

The mills were not described as Dark and Satanic for nothing. This stimulated a tendentious debate about property rights and economic organisation. In this debate there was a continuum of opinion. At one end there was a desire to alleviate poverty and make life easier and pleasanter for people. This expressed itself in Victorian philanthropy and social reform of the sort associated with Lord Shaftesbury and Benjamin Disraeli in Britain, Otto Bismark in Germany and the Progressive Movement in the USA associated with Governor La Follet in Wisconsin and President Thedore Roosevelt. At the other end of the continuum was a desire for revolutionary change to reorganise fully the ownership and organisation of the means of production and replace the conventional price mechanism and markets.Joseph Schumpter explored this vividly in his book Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy published in 1943. Somewhere in the middle of this continuum was a desire for much more collective action associated with the empowering of trade unions in the workplace and tax funded public services to relieve poverty systematically and to provide greater opportunities for people who had not fully benefited from the emergence of bourgeois capitalism. The Christian socialist bishops of the Church of England, such as William Temple the Archbishop of Canterbury, John Maynard Keynes , Lord Beveridge, President F.D.Roosveedlt and the framers of the post-war Ordo-Liberal Social Market Economy in West Germany would exemplify this category of opinion, albeit in different ways..

Socialism pursued for political equity and economic efficiency

There was a further category of political opinion that wanted to replace much of conventional capitalism on the grounds of their perception of both its inefficiency. and inequity. Politically it was led in Germany by the Social Democratic Party’s Gotha Programme adopted in 1875, committing the ‘Socialist Labor Party of Germany endeavors by every lawful means to bring about a free state and a socialistic society, to effect the destruction of the iron law of wages by doing away with the system of wage labour, to abolish exploitation of every kind, and to extinguish all social and political inequality.’ The concept of an iron law of wages was a bowdlerisation of David Ricardo’s principle of economic rent. This was an inadequate theory of value, developed fifty years before by classical economists to explain value and distribution. It was replaced by the principle of relative scarcity in the marginalist revolution in economic thinking that led to modern orthodox neoclassical economics.

The economic rationale for socialism on grounds of efficiency was led by an Italian economist Enico Barone. Barone, working with Vilfredo Pareto, and drawing on the analysis of Leon Walras's conditions for general equilibrium identified the mathematical conditions for paretian optimality in a competitive economy. He went on to develop ideas for an alternative pricing structure based around 'shadow prices' that could be used for a more efficient economy to replace competitive capitalist markets in 1908. This has been described as the 'pure theory of the socialist economy'. This thinking provoked a response from economists in Vienna associated with Ludwig Von Mises. These exchanges contributed to the intellectual development of what has become known as the Austrian economic school that argues that socialist interference with markets and prices damages the capacity of economies to function.

There was a distinctive British contribution to this idea of a socialist planned economy. This came from economists rooted in the marginalist revolution in economics at the end of the 19th century which he synthesised in Alfred Marshall's Principles of Political Economy. Arthur Pigou developed these ideas into a novel form of analytical welfare economics that identified deficiencies in information yielded by market prices, the presence of negative externalities embedded in things such as smoke from a factory chimney that imposes costs to the community that are not borne by a manufacturing firm operating it. This stimulated a socialist agenda for an economy with nationalised industries, extensive controls and much planning and high redistributive progressive taxation of income to equalise income and maximise economic welfare given that utility from income and consumption diminishes at the margin. This became the heart of the Fabian socialist agenda in Britain and across much of the international community that Britain was connected to through its historical empire. Pandit Nehru's post 1947 independent India offers a good example of this thinking, but it was not confined to India.

Britain's relative economic decline in the 20th century

Britain's share of world output was bound to decline as other economies caught up with it and made use of the technologies that it had pioneered after 1780. The use and application of technology internationally, and internally within economies became increasingly diffused. In this process of diffusion new users were better placed to make the most of it, given their geography, access to natural resources, supply of labour and cost structures.

The power of catch up

In the second half of the 19th century America became an industrial powerhouse with the stimulus of a transcontinental economy and economies of scale that for a century eclipsed all other industrial societies. By 1900 the USA had overtaken Britain as world’s leading industrial economy.

The American economy caught up with and overtook the British economy in the 19th century, eclipsing it by 1900

Germany was well placed to adapt to steam technologies and had a science base that enabled it to develop chemical industries.This came, at a time when the economies of Germany were united and further stimulated by the Imperial German Reich’s internal market and new single Reichsmark currency after 1870. In the 20th century the recovery of West Germany after defeat and wartime devastation in 1945, illustrated both embedded German strengths and the advantages of starting afresh from scratch, following comprehensive wartime destruction. After the Meiji Restoration in 1868 Japan demonstrated how swiftly and comprehensively a previously closed society could adapt to the opportunities of new technology through trade.Similar transformations would be demonstrated in Asia in the second half of the 20th century. This process of rapid economic modernisation and success was demonstrated in Hong Kong,Singapore, Taiwan and South Korea in the 1960s and 1970s, Asia's Tiger economies. It was again demonstrated in the People’s Republic of China after 1978.

Inevitably losing competitiveness and comparative advantage in industries Britain pioneered in industrial revolution

Much of the industry developed after 1780 in Britain was specific to geographical circumstances and the application of particular new technologies to them. The comparative advantages that these industries enjoyed at the time of the Great Exhibition in 1851 would be competed away as other economies developed their industries. Activities that turned on extraction. such as quarrying slate and mining coal were finite. The easiest coal to extract first was mined. By the 1920s British coal mines had competition from cheaper producers. This turned on geology as much as social and economic costs. The same could be said of other industries such as ship building and textiles.

The Consequences of the First World War and erroneous monetary policies in the 1920s.

Their aggravated distress in the 1920s arose from two things. The First World War disrupted Britain 's export markets. Britain exported trades were diverted by war and its international customers turned to other supplies, such as Japan that often were more competitive in terms of price. The decision to return to the Gold Standard on the pre August 1914 exchange rate parity, after the inflation of the First World War was a recipe for monetary deflation in the domestic economy and making British manufactured goods uncompetitive in export markets. The slump years of the 1920s were specific to Britain. Other countries returned to the Gold Standard in the 1920s, but at realistic exchange rates where they were competitive in international markets and enjoyed strong post-war economic recoveries, not least the USA.

The Great Depression in the 1930s - an economic history of economic recovery and relatively good economic performance.

The error in British monetary policy was not corrected until Britain left the Gold Standard in 1931 and consistently applied a cheap money policy until 1939. The UK was less affected by the Great Depression than other economies. This partly because unlike Germany and the USA the UK had not enjoyed a boom in the second half of the 1920s. In literary terms America had the Great Gatsby and Britain had D H Lawrence’s Sir Clifford Chatterley in Lady Chatterley's Lover. By leaving the monetary straight jacket of the Gold Standard in 1931 the Treasury was able to apply a powerful monetary stimulus, at a time when it was needed. The result was a smaller loss of output and a faster recovery in economic output in Britain in the 1930s in contrast to other countries.The loss of output was around 6 per cent in the UK in contrast to something closer to 25 per cent in the USA. Likewise Britain had recovered well by 1933, in contrast to economies, such as France that remained on the Gold Standard until 1936.

In the 1930s output recovered strongly in the UK and there was a rapid development of new industries based on electrical and light engineering technologies and motor vehicle manufacturing. The geographical location of economic output shifted to the West Midlands and South East of England. It was a decade of rapid industrial and economic change. Private house building played an important part in the recovery output, in the 1930s unhindered by the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act and credit supported by the cheap money policy after 1931.

One part of the British economy did not recover well in the 1930s. The performance of the labour market was disappointing. Lord Keynes in his articles in the New Statesman identified what he called 'institutional' factors that prevented the labour market from clearing. The international economy and Britain experienced an episode of pronounced deflation in the 1930s. Price deflation raised the real value wages above their market clearing rate. British trade unions would not allow wages to adjust to the changes that followed this deflation. This aggravated the level of unemployment and meant that the rate of unemployment did not fall as output recovered. The economy was blighted by a form of structural unemployment and that probably slowed the pace of economic recovery arising from the powerful monetary stimulus that was present. The heart of this was a defective system of collective bargaining that determined wage rates and work practices in an industrial economy where manufacturing practices and work organisation was changing.

"Institutional' rigidity, Trade Unions, mass unemployment and why the Labour market was the Achilles Heel of the British economy for most of the 20th century

The central problem was excessive trade union power that arose from the 1906 Trade Disputes Act. This exempted people organising trade disputes and strike action from the normal working of the law of tort. It gave trade unions in effect an unusually privileged position in law. For over seventy-five years trade unions would exploit this power in the workplace to raise pay and to resist innovation and change. Until the late 1980s the labour market was the Achilles Heel of the British economy. In the 1930s trade unions gave priority to the higher real wages of their members, who were in work over the interests of people who were unemployed. In the post-war period of mass affluence in the 1950s and 1960s trade unions used their unusual legal immunity to resist change in manufacturing industries. Their behaviour scarred workplaces, such as dockyards, shipyards, car plants, printing businesses and newspapers. They slowed innovation and made necessary changes expensive where they did not completely block them.

The film that satirised British trade union power in the 1950s

Trade union power between the 1940s and 1980s aggravated the problems of industrial sectors such as ship building and car manufacturing that already faced a structural loss of international competitive advantage from competitors in Western Europe, Japan and South Korea.

Keynesian welfare capitalism and the post-war mixed economy between 1945 and 1979

Political economy in Britain between 1945 and 1979 took a distinct turn towards collectivism and socialist economic management. This amplified the relative decline of the British economy in the post-war years and in the 1970s threatened to turn a relative decline into an absolute one. Britain elected a Labour Government led by Clement Attlee. It set about implementing its election manifesto Let us Face the Future. It was a programme of socialist controls, intervention and nationalisation that built on the extensive controls that had been put in place to mobilise the British economy for wartime production in the Second World War between 1939 and 1945. Coal, rail, canals, road transport, gas, electricity and steel were all nationalised. The welfare state was developed along the lines that Winston Churchill's wartime National Government had proposed with one significant exception. Labour introduced a fully socialist National Health Service in 1948. Health care was provided free of charge at the point of use. Hospitals were nationalised. The power to plan, manage and control the service was vested in the minister for health. This created a mixed economy where markets were constrained by regulation and control and many of the principal industries were nationalised

The 1944 Employment White Paper pledged post-war governments to full employment. While in the 1941 Budget Sir Kinglsey Wood promised to maintain full employment through active demand management policy. Labour's Chancellor Hugh Dalton decided to stick to the policy of cheap money that had been in place since the deflation of 1931. Full employment stimulated wage demands. When higher wages threatened employment an accommodating macro-economic policy resulted in inflation that became progressively higher and unstable. The 'authorities' consistently refused to use monetary policy through much of the 1950s and 1960s, which contributed to rising inflation and balance of payments problems. A fixed exchange rate parity against the dollar in the 1950s and 1960s meant that to defend the sterling exchange rate, there was a stop-go cycle of demand management that amplified the usual operation of the business cycle. To avoid monetary and fiscal tightening governments turned to price and incomes policies to control inflation. The powerful British trade union movement that enjoyed great effective legal privileges refused to allow inflation to erode the real living standards of their members. The continuing commitment to full employment, delivered through the maintenance of macro-economic demand resulted in inflation of 25 per cent in 1975. This episode of inflation was one of the worst episodes of inflation in an advanced economy in the late 20th century.

Trade union power in the manufacturing industry, along with controls and subsidies influencing the location of industry and measures to rescue failing firms that would have gone through insolvency proceedings and been closed down, combined to further damage the micro-economic functioning of the economy’s product markets. It expedited the economic logic of closing firms and accepting that Britain had lost its competitive position in sectors, such as volume car production. At the same time policy combined to impede natural economic adjustment. Microeconomic intervention of government departments tended to support dying businesses and contracting sectors. While macro-economic policy also effectively accommodated failing business sectors in the short-term by maintaining demand and keeping down the real cost of borrowing. Prices and incomes policies failed to control inflation. Pay policy destroyed labour market incentives and price controls lowered the rate of return on capital and profits within national income. Two marxist economists Andrew Glyn and Bob Sutcliffe spelt out the consequences of this in their book British Capitalism, Workers and the the Profits Squeeze, writing that ‘without profits to finance dividends and investment, capitalism cannot survive’.

Disinflation and a radical programme of structural economic reform - the 1979 watershed

Close to a generation of necessary change took place in response to the efforts made by British governments to disinflate the economy between 1976. and 1985. From 1979 until 1990 there was a sustained programme of structural reform. This included changes to trade union legal immunities and employment regulation. Prices and incomes policies were abandoned. Profitability and the rate of return on capital were restored. Denationalisation dismantled the mixed economy. Radical reductions were made to marginal income tax rates, taking the top marginal rate of 83 percent with an investment income surcharge of 15 percent down to 40 per cent, and the role of expenditure taxes was increased. At the heart of this programme of radical structure reform, was a recognition of the role that public expenditure can play in crowding out the private sector. The ratio of public expenditure to national income was lowered from a peak of around 48 per cent in the mid-1970s to less than 39 per cent at the end of the 1980s.

UK economy has shown it can adjust to change, de-industrialise and emerge as a post-industrial economy

The combination is a successful disinflation, the dismantling of the mixed economy and the extended programme of structural reform in the 1980s led to an improvement in the relative economic performance of the British economy in the 1980s. The British economy performed in the manner that would be expected of a mature advanced economy. By 2000 inflation was stable at around 2 to 3 per cent, and markets were exposed to international trade which increased domestic competition and greater choice for economic agents. In this process of structural change manufacturing contracted and services expanded. This process of adjustment has continued in the 21 century. As a result services account for over 80 per cent of output and manufacturing for around 8 per cent.

Radical reconfiguration of the location of economic activity

Since the late 1970s the UK has been through a profound process of economic change that has further modified the geographical location of economic activity and the generation of value added.Growth in economic activity has been concentrated in London and the South East of England. While economic activity in traditional industrial areas of the North of England, Scotland, Wales and parts of the Midlands has declined relatively further. This continuing change in the location of the generation of value added, pretty much matches the areas identified in the Special Areas Acts passed in the 1930s.

Necessary economic change has come with unavoidable costs and created a sensibility of nostalgia

A new sensibility of economic and political alienation has emerged. Necessary and unavoidable economic change in local communities associated with the industrial revolution was not matched by new invigorated enterprise in the communities affected. Despite huge attempts throughout the post-war years regional economic development policies were unable in Britain to do what markets had failed to do. The comprehensive apparatus of controls and industrial location certificates and subsidies and planning regulation failed in its policy purpose. In the same way that later attempts at delivering similar policies through the Regional Development Agencies (RDAs) between 1998 and 2010 and devolution of power has disappointed in the devolved British territories and English regions.

There is a distinctive culture of economic nostalgia about industries that had lost their comparative advantages in the 1920s and closed and disappeared forty and fifty years ago. At its heart is an appetite that values manufacturing industries that can be visibly seen. It is apparent in British culture and news media. The closure of the coal industry and the strike action that expedited coal’s inevitable demise is a regular inspiration for plays and documentaries, not least periodic pieces of BBC Radio 4’s Woman’s Hour exploring the National Union of Mineworkers strikes in 1972 and 1984.

The political response to a culture of economic nostalgia in 21 Century Britain

This economic nostalgia has not been lost on British politicians. The Conservative Chancellor of the Exchequer, George Osborne spoke of a revival of manufacturing. In the 2015 General Election he promoted the Conservative Party as the ‘builders’, with the Chancellor dressing in a hard hat and the fatigues of a construction worker. Mrs Theresa May, the Conservative Prime Minister between 2016 and 2019, took this political agenda of regional and manufacturing revival further, embracing an industrial policy. Yet, in a Dutch Auction involving the rhetoric of nostalgia, during the 21017 election, Mrs May’s Conservative Party was eclipsed. Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour manifesto was framed in the Momentum Movement’s anti-capitalism platform of nationalisation and intervention. This drew on a heterodox socialist economics that was influenced by thinking and ideas of economic planning and control that could be traced back to Barone.

Jeremy Corbyn achieved momentum in 2017 election on a tide of socialist nostalgia

Boris Johnson, as Conservative Prime Minister, however, took this nostalgia further with the levelling up slogan, which was an important ingredient in his successful Get Brexit done election in December 2019. Boris Johnson showed that economic nostalgia about regional manufacturing economies could be effectively deployed, politically, by a Conservative politician in an election. Yet translating that economic nostalgia into an effective policy in government is much more difficult.

The sensibility around economic nostalgia developed in Britain, because Britain was not just the first country to industrialise, but the first country to comprehensively de-industrialise. A process well under way by the 1970s and fully explored in the collection of economic papers edited by Frank Blackaby entitled De-Industrialisation and published by the National Institute of Economic and Social Research in 1978. Yet this economic nostalgia is not in any way confined to Britain. America has experienced a similar process of economic change and social trauma.. It is exemplified in terms such as ‘Detroitification’ and the ‘Rust Belt’. In the 1970s and 1980s the main focus of American anxiety was competition from Japanese exports of cars and electronic goods. Since 2008 anxiety has switched to China.

Economic Nostalgia has offered opportunities to construct populist American political narratives

The initial political response came from the Reagan administration in the 1980s. A Republican President committed to free trade, a strong dollar and free exchange rates imposed import controls on Japan and agreed in the Plaza Accord to the managed decline of the foreign exchange value of the dollar against the Yen. It emerged in overtly political rhetoric when Donald Trump framed the 2016 Republican platform on the economic challenge of China, the need to make America Great Again with tariffs as a policy instrument to accomplish that agenda. President Biden’s Democrat platform was about well paying, blue collar, union, manufacturing jobs, a green industrial policy and muscular protection of American industry. The platform was translated into extensive legislation exemplified by the Anti-Inflation Act and the CHIPS and Science Act passed in 2002. The trade policy and the tariffs applied by the Trump administration were retained.

In 2024 President Trump’s Republican ticket won election by promising to take the MAGA - to make America great again - further on a more ambitious policy of protection and tariffs. In office the Trump administration has drawn inspiration for its trade policy from President Mckinley’s legacy when as Chairman of the House of Representatives he secured the passage of the Mckinley Tariff in 1890. This raised the average duty on imported goods to close to 50 per cent. In the 1880s and 1890s tariffs did not not just function as instruments of trade protection. Although that was their principal merit for President Mackinley. They were also sources of revenue yielding tax receipts that were perceived as being responsible for the Federal Government’s budget surplus in the 1880s. The Mckinley Tariffs were contentious, because they raised the domestic prices and contributed to Republican Congressional and White House defeats in the 1890s. Yet in office after 1897, President Mckinley used the protectionist platform to realign American politics in the Republican Party’s favour for the first three decades of the 20th century.

And Europe has not been left out

This economic nostalgia is not confined to Anglo-Saxon post-industrial economies, such as the UK and USA. The European Union has a long tradition of mercantilism. From the original European Coal and Steel Community to the preparations for the creation of the Single Market in 1993 and the French Prime Minister Edith Cresson’s ambition to create a Fortress Europe against Japanese and Anglo-Saxon industrial competition, the EU has framed its policies in the context of a European industrial mercantilism. The French populist right and the left have recruited electoral support as a consequence of de-industrialisation. In Germany nostalgia for a lost planned socialist economy in the eastern lender that made up the GDR, is combined with similar alienation about regional de-industrialisation. Both this nostalgia for a different industrial past and the political expression of communities that have an acute sensibility around their economic performance, played an important part in changing the political geography of the Federal German Republic in the recent election that saw the further emergence of the Alternative fur Deutschland and the Die Linke Partei.

Britain: an industrial society that through a process of creative destruction has adjusted to a post industrial future

Since 1979 the UK has been successful in radically adjusting its economic landscape to address unavoidable and necessary economic change. This has changed the composition of output and employment and the geographical location of economic activity. Its clearest expression has been the rise of the service sector economy and the decline of manufacturing. In the fifty years since Tony Benn coined the expression ‘de-industrialisation’ in an article the 1975 Department of Industry Gazette, the UK economy has for all practical purposes fully de-industrialised. Policy makers have allowed the economy to develop and avoided policies, such as ambitious industrial strategies that are intended to shape the direction of economic output and employment.

In the 1960s the UK monetary authorities allowed the euro-dollar and eurobond markets to develop. These euro-dollar markets swiftly eclipsed the sterling transactions of the City of London and ensured that London emerged as the world’s largest international financial centre. These recycled the petro-dollars, created by the quadrupling of oil prices in the 1970s, further expanding the City of London’s international role. The removal of foreign exchange controls in 1979 and reforms to the London Stock Market, known as Big Bang in 1986 ended fixed minimum commissions and the separation of stock jobbers and stock brokers and allowed international financial institutions to buy them and London’s traditional merchant banks further enhanced the role of international financial services in the British economy. After 1979 policy did not stand in the way of an expanding service sector. There were no experiments with policy interventions such as Selective Employment Tax introduced to shift employment from services to manufacturing. There has been a rapid and little noticed growth in the digital component of GDP.

The ONS defines this as ‘products that are information and communications technology (ICT) goods or digital services and fall within the production boundary of the System of National Accounts’. This now accounts using the OECD definition of output for over 20 per cent of value added. The result is much output and economic activity in services, digital output and activities that relate to brands and intellectual property rights are not visible or easily noticed.

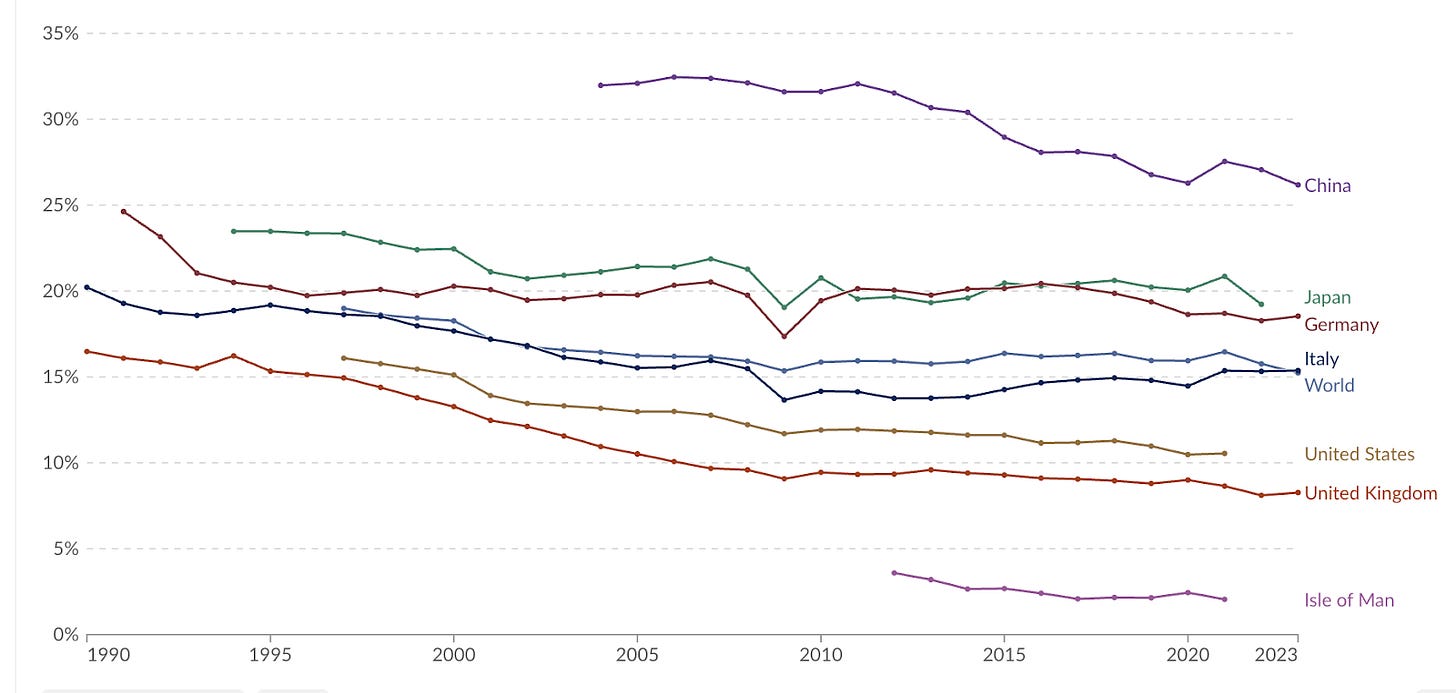

Shares of manufacturing in gross domestic product (GDP), 1990 to 2023

Source World Bank

The relative importance of manufacturing output is falling in advanced economies. This is a long-term trend. This has been particularly evident in dynamic economies that are good at adjusting to changing economic circumstances and have been better at marking structural adjustments. The US and the UK economies are good examples of this sort of change, where the ratio of manufacturing within GDP has fallen to close to 10 per cent and 8 per cent. Within the euro-zone France has exhibited similar adjustment. While Germany and Italy have been much slower to adjust particularly in recent years. In Italy manufacturing continues to account for 15 per cent of value added within GDP, in Germany and Japan the ratio is 19 per cent

Popular and political commentary on economic developments focuses on things that can be seen. These are buildings, roads, factories and industrial plants. Yet much of the value added in the UK’s modern post-industrial economy is invisible to the eye, taking place in the services sector, finance, intellectual property rights and the digital economy. This lack of visibility contributes to the nostalgia about past economic activity and redundant industries that overlooks the changed output of the modern economy.

Warwick Lightfoot

14 April 2025

Warwick Lightfoot is an economist and was Special Adviser to the Chancellor of the Exchequer between 1989 and 1992.