Conservative economic inheritance in 1951, the Stop-Go Economic Cycle and nightmare legacy of A Dash for Growth

Even in the Macmillan Age of Affluence British Governments confronted huge problems from an unrealistic foreign exchange target, ineffectual monetary policy and trade union power.

Conservative Economic Inheritance and Legacy 1951 to 1964

In 1951 the Conservative Party under the leadership of Winston Churchill returned to power. The external economic and financial position of the country was extremely challenging. While Labour under Clement Attlee’s leadership had successfully stabilised the balance of payments by suppressing private consumption through devaluation, taxation and controls. The Korean War resulted in the return of an acute balance of payments challenge as the terms of trade swiftly moved against Britain. Attlee’s government feared a Soviet invasion of western Europe. Moreover, if Europe did nothing for itself America would do nothing either. A significant three-year rearmament programme was therefore agreed. The consequences of this was swiftly exhibited as an overheating economy with balance of payments pressure that would place pressure on an overvalued exchange rate.

Were the problems of Winston Churchill and his Chancellor of the Exchequer Rab Butler, in October 1951 worse than those challenging Sir Keir Starmer and his Chancellor Rachel Reeves in the summer of 2024? The answer is an unequivocal yes.

Korean War, Balance of Payments disequilibrium and a vulnerable exchange rate target

Sir Alec Cairncross’s view was that during the Attlee Labour Government the ‘biggest test of fiscal policy came in 1951 when Hugh Gaitskell had to judge what increase in taxation was called for by rearmament’. The outgoing Labour Chancellor of the Exchequer, Hugh Gaitskell in his April 1951 was therefore exposed to the criticism that given the increased defence spending agreed there was insufficient taxation to eliminate the inflationary gap in the economy. A further criticism of Gaitskell is that he did not take sufficient measures to suppress imports and protect the balance of payments.

As Sir Alec Cairncross expressed it ‘the Korean War played havoc with international prices’. Britain and America having demobilised began to rearm hurriedly. International rearmament contributed to higher world commodity prices and a shift in terms of trade against industrial and manufacturing economies such as Britain. There was a strong pass through from raised international commodity prices into the domestic price level. This was aggravated by defective labour market institutions, a framework of industrial relations law that entrenched trade union power in the workplace. Labour under Sir Stafford Cripps had devalued sterling against the dollar in the Bretton Woods fixed parity system in 1949. Yet maintaining the new parity of $2.80 to the £ would be difficult in a context of inflation, increased defence spending, output being diverted from exports to arms, a vulnerable balance of payments and an exchange rate target that was not perceived to be supported by adequate gold and foreign exchange reserves.

The country was still recovering from the privations of wartime mobilisation. There was still food and petrol rationing and regulation and controls significantly directed resources to economic priorities determined by the government. Moreover, the new Conservative Government like its Labour predecessor wanted to maintain Britain as a world power with an atomic bomb and finance a welfare state broadly agreed to when Winston Churchill was prime minister during the war, with an inadequate economic base to provide for it. The Conservatives inherited an economy exhibiting excess demand. Cairncross spelt out that under Labour from 1945 the ‘situation was always one of excess demand until the moment it handed over to the Tories at the end of 1951’. Excess demand inevitably meant inflation, balance of payments strain and problems with the exchange rate if there is an official fixed exchange rate target.

Welcome to the Treasury: Mr Butler’s lunch at the Athenaeum

Richard Austen (RAB) Butler was appointed Chancellor by Winston Churchill. Rab Butler’s introductory briefing or ‘handover’ was given by Sir Edward Bridges the Treasury’s Permanent Secretary and William Armstrong, his Principal Private Secretary, at the Athenaeum. The historian and former Labour minister Edmund Dell in his book The Chancellors: A History. Of The Chancellors of The Exchequer 1945-90 quoted from Butler’s memoirs, comments that the new chancellor was ‘greeted by dire foreboding about economic prospects.’ Butler recalled gold and foreign exchange reserves ‘draining from the system and a collapse greater than had been foretold in 1931’. Churchill confided to another cabinet minister, Oliver Lyttelton, ‘I have seen a Treasury minute and already I know that the financial position is almost irretrievable: the country has lost its way’.

The new Chancellor in the recently elected Labour Government on 4 July 2024, Rachel Reeves, does not confront comparable immediate economic and financial challenges.

Deflating the economy, reviving interest rate and credit policy

Rab Butler was faced by inflation, excess demand, a balance of payments problem and falling foreign exchange reserves. The new Chancellor took the measures necessary to manage the position. Import controls were used and discriminatory hire purchase controls were introduced to suppress consumer spending on specific items such as the domestic purchase of cars. To protect against pressure on the reserves the Bank Rate was raised from 2 per cent to 2 1/2 per cent. This was a break with Labour’s cheap money policy. Although the Bank of England had advised that the Bank Rate needed to rise to 4 per cent. The March Budget in 1952 was deliberately deflationary to protect the balance of payments and the sterling fixed parity against the dollar.

Post-War Keynesian Consensus: Mr Butskell

The main feature of Conservative economic policy after 1951 was the continuity with the previous Labour government. Churchill’s wartime coalition government had agreed on a broad programme for post war reconstruction. At its heart was an acceptance of the Keynesian revolution and the broad principles for demand management laid out in Lord Keynes’s book the General Theory. The 1944 Employment White paper committed post war governments to full employment. The acceptance of the Beveridge report committed the government to the creation of a welfare state that as Winston Churchill said in a wartime radio broadcast would protect the citizen from the cradle to the grave. Labour had added in government a further distinctive dimension to the emerging British welfare state. The creation of the National Health Service in 1948 this involved the nationalisation of all major hospitals and the full socialisation of hospital medicine in the United Kingdom.

In opposition the Conservative Party that had suffered a shattering defeat in 1945, not only remained committed to the policies that it had agreed to in the Churchill wartime coalition government, but set about ensuring that the public would be confident the Tories had accepted the changes in society brought about by the war. There would be no return to mass unemployment. The government would intervene to ensure full employment. That proposition was central to the Conservative Party’s Industrial Charter published in 1947. Intellectually and ideologically the Conservative Party was a chastened party. In 1951 the instincts of the new Conservative ministers were to complete the process of abolishing the wartime controls that had been initiated by Labour ministers in the 1940s, try to reduce the size of the public sector to some extent and if possible the burden of taxation.

The Conservative Party was clear that its middle-class supporters did not want to see further progress towards socialism. At the same time the party was very anxious about the need to attract working class voters and not appearing to be inimical to traditional working-class interests. As the Oxford economist Peter Oppenheimer wrote in Muddling Through: The Economy, 1951 to 1964 - an essay - contributed to The Age of Affluence edited by Vernon Bogdanor and Robert Skidelsky published in 1970 - these ‘various points did not add up to a coherent political programme or philosophy’. As Phillip Williams noted in his biography of Hugh Gaitskell, this continuity was swiftly spotted by The Economist. The newspaper light heartedly constructed the composite Chancellor of the Exchequer conflating Butler and Gaitskell into Mr Butskell in November 1951. Both Hugh Gaitskell and Rab Butler found the sobriquet irritating.

The Conservatives in the 1950s accepted nationalisation and a mixed economy

As well as the commitment to full employment, Keynesian demand management and the institutions created as part of Sir William Beveridge’s report on social insurance, the Conservative Party accepted the further institutional changes that the Attlee Labour Government made to the British economy. These were the creation of the National Health Service in 1948 and Labour’ s nationalisation of the ‘commanding heights’ of the British economy. The creation of the NHS in 1948 represented the full socialisation of medicine and a centrally planned system of health care, comparable to the USSR’s concepts on planning based on command and control.

In 1951 the Conservative Government inherited a large, nationalised industry sector: the Bank of England; coal; railways; gas; electricity; telecommunication; airways; road haulage; canals; and iron and steel. Apart from steel where the process of nationalisation had not been completed in 1951, the nationalised industries were left in place. The scale of the new nationalised sector was captured by Sir Norman Chester, the Warden of Nuffield College Oxford in his monumental study The nationalisation of British industry 1945 to 1951. Sir Norman estimated that the cost of compensation arising from Labour’s nationalisation programme was £2.6 billion, around 25 per cent of GDP in 1947. Coal nationalisation involved 800 companies and that employed 700,000 people being transferred to the National Coal Board. The nationalisation of transport industries transferred the ownership of 60 railway lines, 1,640 miles of canal, 70 hotels and 50,000 houses. The nationalisations carried out between 1945 and 1950 transferred 2.3 million employees from the private to the public sector. By 1951 one in ten employees worked for a nationalised industry.

This socialised sector significantly changed the structure of the British economy. The nationalised industries accounted for around 20 per cent of output. These public sector monopolies were protected from competition and the normal market processes of contest, challenge and the discipline of bankruptcy. Decisions on their organisation, structure, investment and prices were made outside of the price mechanism in a politicised bureaucratic process where their sponsoring government departments and ministers were the final decision makers. Moreover, health care that would be an increasingly important part of the economy in future decades was fully socialised with the creation of the NHS.

Post-War Consensus offered the electorate a choice: Tweedle Dum or Tweedle Dee

This ‘mixed economy’ part market, significantly socialised, extensively regulated and actively managed through Keynesian demand management tools, was in place for over thirty years. The post-war consensus framed the principal economic decisions of both Conservative and Labour governments. In the Autumn of 1972, my history teacher vividly explained the position. There was agreement on the Keynesian welfare state and in a two-party system, in a general election where voters were concentrated in the centre, a general election was a choice of Tweedle Dum or Tweedle Dee.

Conservative Prime Ministers and Chancellors of the Exchequer

There were four Prime Ministers and six Chancellors of the Exchequer between 1951 and 1964. The period can be roughly divided in half. In the first six years from 1951 the two Prime Ministers were Sir Winston Churchill and Sir Anthony Eden. They took little interest in economic and financial policy. Their principal concern was foreign policy and Britain's place in the world. Sir Winston Churchill was in his late seventies, had had several strokes and was increasingly frail. He no longer possessed the intellectual acuity to interrogate economic policy that he possessed when he was Chancellor in the 1920s. Sir Anthony Eden took little interest in domestic policy and could not be accused of possessing any purchase on finance.

Both Churchill and Eden wanted economic management that was consensual and avoided political trouble. The key was that there should be no return to the mass unemployment of the 1930s. They were politically desperate to demonstrate that the Conservatives could be trusted with full employment and the welfare state. Things that boosted consumption and consumer choice were welcome to these Prime Ministers, so yes to the removal of rationing but no to reducing food subsidies. The Tories were anxious to avoid the caricature of the hardnosed top hatted capitalist of socialist lore. That was why Churchill chose not to appoint Oliver Lyttleton as Chancellor in 1951. In the wartime coalition Churchill had almost appointed him Chancellor when Sir Kingsley Wood died in 1943. Lyttelton as an experienced industrialist and financier would have been across the Treasury brief in a way that Butler was not. Yet Butler was chosen with little knowledge or interest in the substantive departmental issues involved. This was because Lyttleton’s manner and dress invited the sobriquet ‘hard hearted capitalist’. He also had the handicap of being a poor performer on the floor of the House of Commons where the government’s economic policy had to be explained and defended. Butler as Chancellor was the creature of his Treasury officials.

Things began to change in 1956 when Harold Macmillan became Chancellor. As Chancellor Sir Anthony Eden gave him virtually free rein. Macmillan only presented one budget. It is still considered the most amusing budget speech of the postwar years. He compared using official economic forecasts to looking up a train time, in the previous year’s railway timetable. In his short period as Chancellor, he set in motion changes to improve economic statistics such as having quarterly rather than solely annual national accounts data available for economic forecasting.

Harold Macmillan - a Treasury official economic forecast was about as useful as using an out of date railway time table

Before his budget in April 1956 Macmillan I told the House of Commons that it would not be acceptable to allow unemployment to rise as high as 3 per cent . The 3 per cent figure had been considered an acceptable average definition of full employment by Sir William Beveridge. A White Paper the Economic Implications of Full Employment was published by Macmillan in 1956. It explained the challenge of maintaining demand that would ensure full employment, without pressures on the price level that threatened the balance of payments. ‘To maintain full employment without inflation necessarily involves continual adjustments’. Macmillan's view was that the ‘problem of inflation cannot be dealt with by cutting down demand, the other side of the picture is the need for increasing production’. This judgement was to colour economic policy for the rest of the Conservative government until 1964.

Suez Debacle 1956: Britain forced to confront that it is no long a great power

Harold Macmillan became Prime Minister in January 1957. Sir Anthony Eden had resigned after the failure of his foreign policy and the debacle of the joint Anglo-French operation to seize the Suez Canal in 1956 that the Egyptian government had nationalised. A key part of Britain's decision to abandon the military operation was American opposition to it and the refusal of the Eisenhower administration to help support sterling which was falling on foreign exchange markets. Without US and IMF assistance sterling would have had to be devalued or the pound would have had to float. Not only did the US Treasury refuse to support sterling, it actively blocked the UK from having access to IMF assistance to which it was entitled. The failure of Suez had profound implications for Britain’s future role as an independent actor on the world stage. Suez, moreover, led to a rapid appraisal of Britain's remaining imperial role and expedited the process of decolonisation in Africa and the Caribbean.

The Macmillan Age

Harold Macmillan as Prime Minister was a dominating figure. He was the longest serving prime minister in the 20th century since Herbert Asquith. In Macmillan A Study in Ambiguity Anthony Sampson described Macmillan’s six years and nine months in office a ‘period long enough, and defined enough, to have some meaning as the age of Macmillan’. When he moved into the traditional No 10 Downing Street official residence of the prime minister, Macmillan had distinctive theatrical style.

It was a calm, phlegmatic, Edwardian style. A cultivated exercise in sangfroid following the Suez crisis. A prime minister who relaxed by reading the novels of Anthony Trollope. This was an artificial and contrived persona, and was transformed into something much more flamboyant by the press. Macmillan became ‘Supermac’ and ‘Macwonder’, the Prime Minister for mass affluence. As Macmillan told a Conservative Party rally at Bradford in July 1957 ‘Let us be frank about it; most of our people have never had it so good’. He was the first television prime minister. Macmillan enjoyed the medium and was not afraid of using it.

Macmillan was married to the daughter of the Duke of Devonshire, Lady Dorothy. He was a wealthy publisher. In the 1930s he had helped to run the famous publishing house Macmillan, as director. He lived in a substantial country house inherited from his mother, Birch Grove at Chelwood Gate in Sussex. Through his family’s publishing business as a young man Macmillan was introduced to many of the intellectual and literary figures of the period Not the least of these was Thomas Hardy O.M. who along with a string of other famous authors attended Harold and Dorothy’s wedding in April 1920. Macmillan liked shooting and he loved country houses. The aristocratic manner came easily to him, even if it were affected with a degree of theatrics.

Yet this affected manner should never have been mistaken for a lack of hard work, professionalism or an amateurish approach to transacting government business. Macmillan was the director of his family’s publishing company who had looked after books on economics, politics and social problems. Among the authors he managed were E H Carr, GD H Cole and Keynes. A Canadian, Lovat Dickson joined the firm and noted that ‘beneath the bland appearance of a typical young Conservative politician of the 1930s, he had an extremely keen and incise brain’. It was not an accident. Macmillan had a scholarship to Eton, went up to Balliol College, Oxford with an Exhibition, and took a first-class degree in Classics Honour Moderations in the summer of 1914. Sampson considered that ‘Balliol had … given him an exceptionally well-trained mind, which could see through very difficult problems…As with Asquith before him, it was this cool intellectual mastery that gave him the key to the top.’ Macmillan in short was anything but an inane upper-class buffoon.

Conservative Prime Minister with a determined economic expansionary agenda

Macmillan moreover had a developed economic agenda. Through his work as a publisher at Macmillan, he knew Keynes and was among the politicians that accepted the rejection of traditional Treasury orthodoxy and Keynes’s ideas about demand management. In the 1920s and 1930s in his constituency in the north of England, Stockton on Tees he had first-hand experience of the mass unemployment of the slump years. He published a book The Middle Way in 1938 that advocated the abandonment of laissez-faire and advocated the use of economic planning. As Chancellor and Prime Minister, he was determined that there should be full employment. Whatever inflationary and balance of payments problems there may be the Treasury, and its ministers from the chancellor down, should not be allowed engage in deflationary conceits that put full employment at risk. As the late 1950s progressed Macmillan became increasingly attracted to intervention and planning that could raise the productive capacity and growth of the economy. In the early 1960s Macmillan got the economic policies he wanted. The conclusion of the long thirteen-year period of Conservative government in the early 1960s was a dash for growth with serious malign implications for inflation, the balance of payments and the sterling exchange rate. It bequeathed a balance of payments in fundamental disequilibrium that had to be managed in the Bretton Woods fixed parity exchange rate regime.

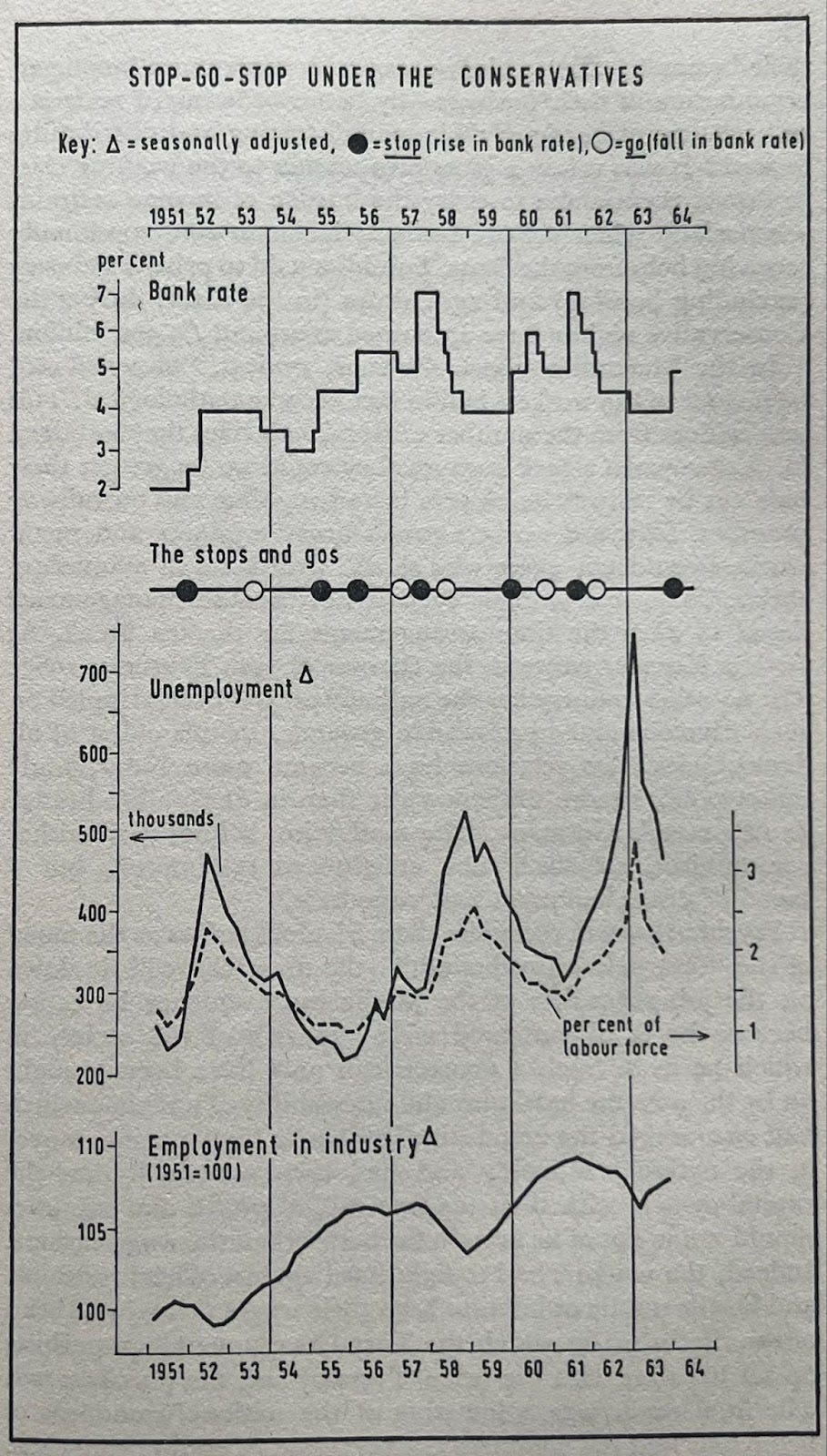

Keynesian Demand Management: the Stop–Go cycle

Conservative economic policy during the 1950s and 1960s was distinguished by great prosperity and affluence. Yet a pattern emerged where the economy expanded, overheated, began to exhibit price pressures, encountered balance of payments constraints that placed pressure on sterling. There began a pattern of fiscal and monetary tightening that was then followed by a loosening and expansionary macroeconomic policy that stimulated economic activity once again. Demand was managed and fine-tuned. Chancellors, such as Macmillan compared it to steering a car. The economic analysis that informed this economic fine tuning was based on data that was lagging and the policy instruments that took effect with variable delay. The result was that the breaks were put on too sharply. As unemployment rose the breaks were then taken off and the accelerator was hastily reapplied. There was no return to the slump or depression of the inter-war years. Full employment was successfully maintained. But the economic cycle had not been abolished. Keynesian demand management appeared to have instead speeded up the traditional economic cycle. The complaint that emerged among economic commentators was that expansion and growth was too frequently retarded by the stop phase of the Stop-Go cycle. A stop go cycle that hindered the long-term growth and expansion of the economy.

Samuel Brittan’s classic illustration of the post-war Stop-Go economic cycle

Source The Treasury under the Tories 1951-64 published in August 1964

Full Employment, Inflation, Pay and Bad Industrial Relations

The consistent application of the full employment policy meant that demand in the economy exceeded the productive capacity of the economy to produce without price pressures and balance of payments problems. These pressures were aggravated by the structure of trade union law and industrial relations. Labour market institutions had been clearly defective for more than a generation. Full employment made it more difficult for employers to resist trade union pressure for higher pay and to manager their workplaces. Nationalisation had expanded public sector employment and politicised it. The government owned public corporations, set their objectives, determined their investment programmes and their external financing limits.

From its start in 1951 the Conservative Government was determined to appease the trade unions avoiding strikes at all costs. Sir Walter Monckton, a prominent solicitor and negotiator, was appointed Minister for Labour. The Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s guidance to his Labour Minister was clear: avoid strikes and industrial trouble. As a Conservative minister he was not allowed to attend the Conservative Party Conference for three years, because he was supposed to be perceived as a non-partisan arbitrator. A good example of the policy in practice is offered by Rab Butler the Chancellor. In 1953 against his wishes Churchill and Monckton settled a railway dispute over pay that had threatened travel over the Christmas holiday period. The Prime Minister phoned Butler to tell him they had settled. When the Chancellor asked on what terms they had agreed. The Prime Minister airily responded, ‘Theirs’ old cock’.

The result of this policy was rapidly rising wages within national income. As Chancellor Harold Macmillan pointed out in September 1956 that since 1953 in Germany and America wages had risen in line with output. Whereas in Britian wages had risen twice as fast as output per head. Cost pressures from the private and public sectors were accommodated by monetary and fiscal policies that were resolutely focused on maintaining full employment. Samuel Brittan writing in The Treasury under the Tories 1951-1964 commented ‘Appeasement did trade unionism little good, as higher wages were largely cancelled out in higher prices…the price for the Monckton policy’ was the ‘pricing British goods out of world markets slowed down the growth of the whole economy’.

Emergence of a Pay Policy to control inflation in early 1960s

As the years progressed policy makers in the Treasury became progressively more concerned about wage growth and more anxious to have some form of policy to curb incomes. The preferred reflex of ministers was to invite and hope for a change in the climate of opinion among wage negotiators. Rab Butler in his Budget Speech in 1954 told Parliament that ‘we do better through relying on voluntary moderations.’ Harold Macmillan and his chancellors engaged in exhortations calling on trade unions and employers to only agree realistic pay settlements. After the departure of Sir Walter Monckton from the Ministry of Labour the department continued his approach on pay. This amounted to conciliating any pressure irrespective of the economic, financial and other damage it may involve. This reflex changed when Sir Laurence Helsby, a former economics dons with the Treasury experience became the Ministry of Labour’s permanent secretary in 1959.

Ministerial exhortation on pay became more intense and evolved into an ambition to have a pay or incomes policy. The Prime Minister Harold Macmillan saw wage control as the means to contain inflation without deflation. His Chancellor Selwyn Lloyd announced a ‘pay pause’ for 1961-62. This produced immediate beneficial effects. These atrophied as the policy evolved and became more flexible in order to manage the anomalies that it exhibited. Conservative ministers remained determined to maintain wage restraint and in 1962 a White Paper Incomes Policy: The Next Steps was published. This set out the case for pay moderation. It introduced the concept of a ‘guiding light’ for pay settlements and the criteria that people involved in setting pay such as arbitration tribunals should take into account. The White Paper came down against notions of pay comparability, increases in the cost of living and improved productivity as justifications for increased pay.

The principles of the White Paper were swiftly honoured in breach than observance. Harold Macmillan himself invited the railway unions to No10 Downing Street to settle a threatened strike. This did not prevent the Prime Minister from setting up a National Incomes Commission, chaired by a lawyer and boycotted by the TUC that was wholly ineffective. Where a settlement breached the national interest and had been agreed without the advice of the Commission the Government could refer the proposed pay agreement to it. As Edmund Dell noted it was an ex post facto review and only three cases were referred to it.

Paish-Phillips trading off some modest increase in unemployment for low inflation?

Treasury officials like Sir Robert Hall and outside economists such as Thomas Balogh at Balliol College Oxford and G.D.N. Worswick argued that income policy would be an effective way of reconciling full employment with low inflation. Other economists thought that greater realism about the rate of unemployment would take sufficient excess demand out of the economy for price and financial stability. Professor Frank Paish and Professor Bill Phillips at the London School of Economics considered that a modest increase in the rate of unemployment to 2 or 21/2 per cent would substantially reduce inflation. Frank Pais also suggested that permanently holding demand slightly below the full capacity of the economy could take the UK out of the Stop-Go cycle and accommodate steady growth at the economy’s trend rate. Many Treasury officials shared this ‘Paish Theory’ or the ‘Paish Thesis’ and some had come to similar thinking independently. This sufficiently occupied the intellectual attention of the Treasury in the early 1960s to merit a separate appendix in Samuel Brittan’s book's ninth chapter What Went Wrong as Appendix: An Influential Doctrine.

A Labour market that was inflexible disfigured by toxic social relations

The labour market was inflexible; it had been the Achilles Heel of the British economy for thirty years. The unemployment and other economic problems of the 1920s and 1930s were significantly aggravated by the lack of price adjustment in real wages to changing economic circumstances and shocks. Trade union power and the immunities given to organisers of trade disputes in 1906 were at heart of it. There was further hindrance from an archaic structure of trade unions, craft unions, working practices, demarcations and closed shops. Full employment compounded these problems. Conservative ministers feared a politicised trade union movement. There was a broader sociological and class background that made industrial relations toxic.

Cathy Come Home the story that helped to expose the disappointment with the welfare state in relation to poverty

It was explored in Alan Hackney’s novel Private Life made into a satirical film I’m All Right Jack, where Peter Sellers gave a memorable performance as a shop steward. John Braine’s novel Room at the Top was also turned into a film that portrayed a sombre industry working class community. Arthur Koestler edited a collection of essays Suicide of a Nation: Enquiry into the State of Britain that offered diagnosis of a deep class antagonism. A malfunctioning labour market, defective trade union law and bitter class antagonism were a potent malign challenge for the management of the economy. The effective power of trade unions in the workplace was reflected in a shift in factor shares within national income. The ratio accounted for by profits fell and the ratio of labour income rose.

Source: The Split Society Nicholas Davenport, 1964

Planning, expansion and breaking out of the Stop-Go Cycle

Harold Macmillan had a long-standing interest in economic intervention and planning. His book the Middle way was occupied by detailed proposals exploring how government intervention could improve on the functioning of markets. As the 1950s progressed there was increasing anxiety about inflation and about the UK economy appearing to grow more slowly than other economies. The 1950s were the years of mass affluence. Growth was faster than at any time in recent British economic history. As Chancellor Rab Butler talked about the country doubling its standard of living in a generation. Yet other economies such as West Germany, France and Italy were growing faster. The British economic establishment acquired a neurosis about the threat of relative economic decline that the German and French economic miracles presented.

Everything they wanted to get away from : The Tory Stop-Go cycle as illustrated by Nicholas Davenport

Source The Split Society Nicholas Davenport 1964

Leading industrialists, such as Sir Hugh Beaver the Managing Director of Guinness and Sir Reay Geddes Managing Director of Dunlops were among leading members of the Federation of British Business – the FBI - that became attracted to the model of post-war French Indicative Planning and its institutions, such as the Commissariat du Plan. The official Treasury, at the same time became interested in planning, and when Selwyn Lloyd suggested the idea to Harold Macmillan, the Prime Minister enthusiastically supported his Chancellor.

This led to the establishment of the National Economic Development Council -NEDC in 1962. It was a tripartite organisation that brought together government, employers and trade unions. It was serviced by its own secretariat and economic advisers. The TUC was enthusiastic about its participation in it, but made it clear that it did not see pay being planned as part of the NEDC’s work. The NEDC’s also supported sectoral working parties that looked at individual industries such as the motor industry. The purpose of this planning initiative was to raise the trend rate of economic growth to match that of the UK’s western European neighbours.

The European neuroses of the British economic establishment in the 1960s: the strong relative economic growth of National Income in the 1950s in Germany, France and Italy

Source: The Split Society Nicholas Davenport published 1964

An important part of the thinking that inspired it was spelt in a speech made by Sir Hugh Beaver. He argued the problems of inflation, and too much demand that could not be matched by output, that was behind the stop-cycle, should be tackled by raising the productive potential of the economy through economic growth. Raising the economy’s productive capacity to maintain expansion should be the preferred course of action. Growth should be given priority over deflation and fiscal and monetary measures to protect the balance of payments and the exchange rate.

This chimed happily with Harold Macmillan’s thinking over many years. Macmillan had not written the Middle Way for nothing in 1938.It was moreover applauded by the country’s leading economic commentators of the period. These included Michael Shanks the author of The Stagnant Society, Sir Andrew Shonfield, in Modern Capitalism wrote of a new economic order that could be seen in an acceleration of economic growth, Samuel Brittan whose book The Treasury Under the Tories 1951-64 recorded the detailed exchanges over economic policy economic policy within the British business, administrative and political elites. The Labour Opposition shared the analysis and instinctively supported the remedy. Harold Wilson, when Shadow Chancellor, as Samuel Brittan pointed out, had been among the first people to draw attention to a league table of economic growth that found Britain wanting. As Britain entered the 1960s there was a perception of excitement, new opportunities and different ways of doing things in economic policy in particular.

How the NEDC got to a 4 per cent annual growth rate for the UK economy in 1962

Samuel Brittan’s book sheds interesting light on the thinking of NEDC and its supporting economists. The gobbets below speak for themselves:

The NEDC economists ‘believed, on the basis of their own statistical studies, that the underlying trend of productivity had speeded up in recent years, and that this had been hidden from view by the depressed conditions of 1961- 2.’

‘The real reasons for giving the EDC the ‘benefit of the doubt lay in the physical changes that have taken place in British industry too recently to show up in a long run of figures, for which the Treasury then failed to make sufficient allowance.’

‘It was moreover quite obvious from actually looking at industry, reading company reports, or talking to businessmen, that most firms had had a big competitive shakeout. Many of them had launched drives against the wasteful uses of labour.’

‘All over the country industrialists were insisting that they could increase output by very large amounts with very small increases in their labour force.’

‘The big weakness of the whole Treasury attitude to growth was that it was tied to the past.’

‘The novelty of the NEDC was that it tried to find out from industrialists what they could actually do in their present and future, if the demand was there for their products and the different sections of the economy moved in phase.'

‘On the basis of businessmen's estimates, cross checked for consistency with each other and with the probable growth of the labour force, a 4% growth rate was regarded by industry as physically possible’

As Brittan helpfully explained that the NEDC was created against a changed international background. The new Kennedy Administration set a target for advanced western industrial economies to grow by 50 per cent over ten years. This goal was set at meetings of the OECD. The OECD was the successor to the OEEC, the Marshall Plan’s economic secretariat based in Paris that analysed the success of economic policy. The 50 per cent ten-year growth target translated into 4 per cent a year. Across the OECD, it would come from the new Kennedy Administration moving the US economy closer to full employment than under the Eisenhower Administration and the recent growth record of the European Common Market formed in 1957 would continue, although by 1962 the EEC rate of growth was beginning to fall.

The British Treasury thought that the UK economy could annually grow by 3 per cent. Given the Treasury’s concern about public expenditure control and the balance of payments, its officials were not minded to be optimistic. The NEDC therefore thought there should be a faster target that was more ambitious was therefore appropriate. A 4 per cent growth target also neatly matched the international ambitions of the OECD and the Kennedy Administration in Washington DC.

Peter Thorneycroft’s attempted financial control

Harold Macmillan had four Chancellors of the Exchequer: Peter Thorneycroft, David Heathcote Amery, Selwyn Lloyd and Reginald Maudling. On important matters such as foreign policy and the economy Macmillan liked the ministers who headed the relevant departments of state to be malleable and effectively under his direction. At the Treasury this meant no chancellors who harboured deflationary conceits.

Peter Thorneycroft’s brief tenure in office, however, merits exploration. Peter Thorneycroft’s appointment did not work out politically. Thorneycroft was not an economist but was seriously interested in economics and finance and entered the Treasury as an experience economic cabinet minister having been President of the Board of Trade. In was one of the MPs who voted against Hugh Dalton and Lord Keynes’s American Loan in 1945.

Thorneycroft was supported by two Treasury ministers who were clever ideological supporters of free markets, financial discipline and inflation control – Nigel Birch and Enoch Powell. As a new chancellor in 1957, Thorneycroft set about deflating the economy in the normal manner. It was the point in the Stop-Go Cycle when things had to stop. But Thorneycroft decided to take things a stage further and as he saw it address Britain's inflation and excess demand problems directly at their route cause. He and his ministerial colleagues wanted to control the money supply, make much more aggressive use of interest rates and monetary policy tools to control inflation. As part of this Thorneycroft established the Radcliffe Inquiry into the conduct of monetary policy. Thorneycroft and his ministers also wanted much tighter control over public expenditure.

The Chancellor and his ministers wanted reductions to departmental spending estimates. These were resisted both by spending ministers and the Prime Minister. Moreover, the Chancellor’s own Treasury officials were unsympathetic to what they perceived as a clumsy misplaced reassertion of traditional financial rectitude that was redundant in the modern post war world as they saw it. Sir Robert Hall, the chief economic adviser, thought the economy needed to be cooled but felt there was no need for urgent or particularly decisive measures. While the economy was strong the balance of payments forecasts were good and overfull employment was moderating. For Sir Robert Hall Thorneycroft’s proposals were probably politically impracticable given the opposition in the Cabinet, and economically undesirable. Edmund Dell comments in his book on The Chancellors, Hall's optimism was sadly premature, as Hall would later have to admit. Thorneycroft’s instincts about the real state of the economy had more validity than Hall’s economic amylases. The episode was an illustration of Macmillan’s complaints about the unreliability of Treasury economic forecasts.

Harold Macmillan’s Little Local Difficulty

When Macmillan and the Cabinet would not agree to the cuts in spending, Thorneycroft and the whole Treasury ministerial team resigned in January 1958. Politically Macmillan rode the storm out with great aplomb. He flew off on a Commonwealth tour with the Cabinet lined up at the airport to see him off, in an ostentatious display of support. Macmillan dismissed the resignations as ‘a little local difficulty’. It was played as another example of the stylish old Edwardian’s sangfroid.

In post-war Britain there were no political prizes for controlling inflation

In terms of post-war Conservative Party economic history the episode was politically instructive. It was the only occasion when a Conservative Chancellor made a stand on controlling public spending and taking decisive measures against inflation through monetary control. The reward for this was political oblivion.

Courageous, Principled, John the Baptists of a future monetarist counter reformation

At the time Thorneycroft and his Treasury ministers were perceived as unhelpful, naively informed political ideologues. In this thinking they displayed a narrow and irrelevant financial rectitude. A rectitude that Macmillan was able to dismiss airily as ‘fanaticism’ over financial matters. Things were not helped by the official Treasury and its economists. The Treasury was increasingly wanting to develop new micro-economic controls over pay to deal with the increasing macro-economic problems of their great Keynesian intellectual heritage. Its officials considered the concerns of their ministers and Chancellor to be largely beside the point. Yet Peter Thorneycroft and his ministerial colleagues were to turn out to be the political John the Baptists of Britain's later monetary counter-reformation in the 1970s and 1980s. Even writing in 1970 before the inflationary crisis of the mid-1970s, Peter Oppenheimer commented that ‘bankers and economists found much to criticise in Thorneycroft’s analysis, but from a practical standpoint his main mistake was to be ten years and several Governments too early. It was left to a Labour Chancellor to apply his medicine in something like its full rigour’.

Sir Roger Makins – Harold Macmillan’s egregious treasury appointment

In many respects, the public expenditure row that took place between the Prime Minister and spending ministers on the one hand, and the Chancellor on the other, sheds light on the working relations between ministers and their Treasury officials. Or more precisely how they broke down. In 1958. There is even the suggestion that the Treasury at a senior level may have briefed Number 10 against their own Chancellor.

Matters were not helped by the recent arrival of a new Treasury Permanent Secretary. Sir Roger Makins was educated at Winchester and Christ Church College, Oxford. He was a diplomat, who was personally close to Harold Macmillan. Makins had a first in history and had been elected a Prize Fellow of All Souls College Oxford He was considered by Sir Isiah Berlin to possess the best second-rate mind in the country. By the time he arrived at the Treasury, Macmillan was gone.

Makins was a man who knew little about his new department or about economics and finance. In practical terms he did not need to. Makins benefited from significant inherited wealth and having married an American heiress. Lady Makins’s father Dwight Davis had served in President Coleridge’s Cabinet, as Secretary for War and founded the Davis Tennis Cup. Makins was very well connected, astute and knowledgeable about all things American. An example of this was that as British Ambassador in Washington, at the time of Suez in 1956, Makins was clear that the Eisenhower Administration would not support the Anglo-French intervention. Somehow this critical judgement was not translated into effective advice to the Foreign Secretary.

In what to Makins, was the comparatively dowdy world of the 1950s Treasury, he was an ingénue. Samuel Brittan described making Sir Roger Makins the Joint Permanent Secretary of the Treasury, in charge of economic and financial policy as ‘a bold gamble that did not quite come off. The country's economic problems were too complex for anyone, however intelligent, with a mainly Foreign Office background, to pick up overnight’.

Richard Wevill,Makins’s biographer in Diplomacy, Roger Makins and the Anglo-American Relationship concluded that his Treasury appointment ‘was something of a disaster’. Makins’s American connections did help, as Richard Wevill explains in getting American assistance, during the Suez crisis, but this was very much a result of, who Makins knew, at the US Treasury Department rather than the employment of any economic or financial expertise. Richard Wevill explains Makins’s failure at the Treasury as arising from two connected things: Firstly, Makins had no experience or knowledge of domestic finance or indeed monetary policy. Secondly , he loathed the work’. During the arguments between the Chancellor Peter Thorneycroft, and the Prime Minister and Cabinet, Makins saw it as his job to protect the Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan and the wider political interests of Macmillan’s government. Even if that involved, to paraphrase Dame Evelyn Sharp, selling his minister down the river.

ROBOT Junking Bretton Woods and floating sterling

The ROBOT policy review of exchange rate policy merits particular exploration. ROBOT’s key suggestion was that sterling should float. The issues raised in the paper expose the constraints that the Bretton Woods System of fixed parity exchange rates imposed on Britain. It is a story about a policy that never happened, that should have happened and eventually did happen nineteen years later. Given the sensitivity of the paper it was given the acronym Robot, which was a play on the initials of the names of the officials involved in drafting it.

Floating sterling was a highly sensitive and secret policy proposal that explored the merits of allowing sterling to float on foreign exchange markets. It would have effectively meant junking the foreign exchange rate target against the dollar within the fixed parity Bretton Woods System. The issues were principally taken up by the Chancellor Rab Butler shortly after his appointment in 1951.

The Government’s problem was that it had an exchange rate target that was difficult to meet. First because Britain had insufficient gold and foreign exchange reserves to mount reliable open market operations to protect sterling in episodes of temporary sterling weakness. An exchange rate target inevitably resulted in balance of payments problems during the course of the economic cycle because the exchange could not adjust to balance the capital account for changes in domestic demand. This meant that periods of strong expansion had to be curtailed by domestic deflation to protect the balance of payments.The 2.80 parity against the dollar was fundamentally uncompetitive in the longer term and not consistent with balance of payment equilibrium. There was a compelling reason to consider floating given a shortage of international liquidity. This crucially meant a shortage of dollars that would present a recurrent problem for an economy with a fixed foreign exchange target and a weak balance of payment.

Official advice in the Treasury was divided on the suggestion of floating sterling. Sir Leslie Rowan the Treasury’s Head of the Overseas Finance Section and Sir ‘Otto’ Clark, Sir Edward Bridges the Head of the Treasury, Sir George Bolton an executive director of the Bank of England and Governor Cameron Cobbold supported the paper advocating ROBOT. Sir Edwin Plowden the Head of the Treasury’s Economic Planning staff, Sir Robert Hall the chief economic adviser at the Treasury all opposed it. Rab Butler supported the proposal and took it to the Cabinet, not least because of the continuing loss of foreign exchange reserves. In the end the proposal to float the pound was rejected by the Cabinet. The only minister who supported the Chancellor Rab Butler was the Secretary of State for the Colonies Oliver Lyttleton who was the Cabinet’s only experienced industrialist.

Dreaming about international financial institutions that might make life easier for Britain

At various stages between 1952 and 1963 Prime Ministers and Chancellors would, when sterling was under pressure, consider revisiting the issue of floating sterling. The other variant was attempts to promote reform of the international monetary system to increase liquidity and attempts to obtain support for sterling from the US and economies such as West Germany that had permanent tendency to balance payments surplus. Harold Macmillan took a keen interest in the issue of a lack of international liquidity, or as he put it, internationally acceptable cowrie shells. Macmillan enjoyed reminding people that Lord Keynes when negotiating the Bretton Woods system in 1944 had advocated the creation of an international currency Bancor. The difficulty was that the Americans had rejected Keynes’s ideas in 1944 and remained opposed to Macmillan happy whimsies. The US voice of opposition was expressed through Per Jacobsen, the Swedish Managing Director of the IMF.

Neither the Germans nor the Americans would help

Macmillan also tried out his ideas on West German ministers. Macmillan explained that countries that had a balance of payments surplus had a duty to revalue their currencies to make life easier for their competitors. Konrad Adenauer, the West German Chancellor, who domestically ran a tight monetary and fiscal ship – he was accused of having created a ‘Julius Tower’ to store the accumulated treasure of his budget surplus – had none of it. German policy and the deutsche mark would be managed in the interests of West Germany. His economics minister Ludwig Erhard the author of the West German Economic Miracle was blunter. As early as 1956 when Macmillan was Chancellor, Erhard commented that sterling was overvalued and needed to be devalued.

The Maudling Plan – a Mutual Currency Account that nobody was interested in

An example of Britain's attempt to obtain international assistance for its problem was the ‘Maudling Plan.’ This was a Mutual Currency Account scheme presented to the IMF and international finance ministers in September 1962 at the annual World Bank /IMF meeting. It was a complicated set of proposals that were barely intelligible to finance ministers, yet its purpose was easily grasped by them – essentially a request to accommodate the support for sterling as a reserve currency, while allowing it to engage in expansionary and inflationary policies. It was opposed by the US Treasury Department and the West German Government. As Edmund Dell wrote “British governments should have been learning that in an increasingly open and ‘interdependent world’, Keynesianism in one country was not viable.’’

The brutal truth was that Conservative ministers flunked a critical decision about the viability of their policies. Their full employment policy created recurrent excess demand in relation to productive capacity. The only way the fixed exchange rate target could be maintained in relation to an overvalued exchange rate logically was through an internal devaluation. Sustained deflation to make an uncompetitive exchange rate consistent with local demand was both inconsistent with the full employment policy pursued since 1945 and could not be reconciled with the ambitions for expansion and economic growth that the government and informed opinion increasingly supported from the late 1950s.

Devalue or bite the bullet and let sterling float on the foreign exchange markets?

It was not an accident that the two most senior economists brought into the Treasury from Cambridge by the Labour Chancellor after 1964, Robert Neild and Lord Kaldor advocated devaluation. Robert Neild made it clear that the big question was not devaluation but whether sterling should float or not.

When the NEDC worked on its paper Conditions for Faster Growth in 1963, for example, its members occupied six days on the question of the role of the exchange rate and whether sterling should be devalued to promote export-led growth. When the paper was published that section of analysis was not included at the request of the Treasury. Among the influential economists at the time who advocated devaluation to facilitate growth that would not involve stimulation of the home market, but exports led growth was the Cambridge Keynesian economist Lord Kaldor.

The issue of devaluation in 1964 was brought into focus as a result of an over-expanding economy exhibiting balance of payments problems that could not be managed by a fixed exchange parity or alternatively a formal public devaluation of sterling. This was the macro-economic inheritance of Harold Wilson’s Labour Government elected in October 1964. It was the fall out of Reginal Maudling’s ‘dash for growth’.

Reginald Maudling: an easy-going chancellor with no deflationary conceits - Macmillan had finally found his sort of finance minister

Reginald Maudling was Macmillan’s final Chancellor, appointed in 1962. It was part of a ruthless reconstruction of the Conservative Government known as the Night of the Long Knives. Maudling was a highly intelligent man who had read history at Oxford, worked as a researcher in the Conservative Research Department, served as a junior Treasury minister and as President of the Board of Trade. Maudling was articulate and enjoyed an easy fluency when discussing economic issues. He was not dependent on either a Treasury brief or notes when speaking.

As Chancellor of the Exchequer Maudling picked up the Macmillan Government’s enthusiasm for planning, expansion and growth, and ran with it. The commitment to growth and expansion was broadly shared by the official Treasury, economic commentators and business opinion. It was based around several stylised propositions. These were that the economy should be expanded and economic growth would provide the productive capacity to square the inflationary and balance of payments problems that had retarded progress over the previous decade of Stop-G0.

Maudling in the traditional Mansion House Speech – an address made each by the Chancellor of the Exchequer at a banquet given by the Lord Mayor of London for the ‘Merchants and Bankers of London’ – the Chancellor responded to this zeitgeist of this economic and business opinion. He explained that there was an international threat of deflation that arose from a shortage of international liquidity, his purpose was to persuade advanced industrial countries to undertake an internationally coordinated expansion of demand. Maudling announced a significant loosening in domestic monetary conditions. This was principally through easing controls of bank deposits and credit controls. There were also measures announced to raise public investment in nationalised industries and the lower purchase tax on cars from 45 to 25 per cent. This was perceived as important because motor car production in that epoch was considered the key to industrial and economic success.

Maudling’s Dash for Growth

Maudling took up the increasingly fashionable economic consensus that faster economic growth was the answer to inflation by reducing unit costs. Reduced unit costs arising from higher production was the key to export success and solving Britain’s endemic balance of payments constraint. Edmund Dell explains that ‘Maudling’s peculiar contribution to British economic policy,’ was ‘to endorse as chancellor the idea of the dash for growth’. In his April 1963 Budget Speech the Chancellor said ‘Not only is it untrue that expansion and a strong pound need conflict: in fact the two depend upon one another’. There would be a virtuous circle where expansion would increase output, economies of scale would lower unit costs, which would make exports more competitive and balance the current account. This became known as the ‘Maudling Experiment’. Edmund Dell makes the acute observation that this dash for exports was announced at a time when world trade was expected to increase more slowly than before; and as an approach very different from Selwyn Lloyds exports promotion that was based on restrictions on home demand to accommodate increased export production.

Maudling’s Budget Speech announced a ‘guiding light’ for economic growth of 3 to 3.5 per cent. This revised growth target was in response to the NEDC target of 4 per cent for growth in national production set out in its paper Conditions for Faster Growth in April 1963.It was predicated on annual productivity per head increasing by between 3 and 3.5 per cent. Maudling marshalled all the instruments of macro-economic policy with the purpose of expansion: a large increase in public expenditure, substantial reduction in income tax, tax reliefs and other measures to encourage investment and a large borrowing requirement. These sources of fiscal stimulus matched by the loosening in monetary conditions and the reduction of the Bank Rate to 4 per cent.

Labour’s critique of the dash for growth – Maudling was not stimulating enough

The reaction to Maudling’s Dash for Growth was politically fulsome. Harold Wilson as Leader of the Labour Opposition welcomed the April 1963 Budget with praise. The only question and a point posed by the Labour Shadow Chancellor James Callaghan whether Maudling had ‘been too cautious’’. This critique of not doing enough made by Callaghan was echoed by Anthony Crosland the former Oxford economics don and Roy Jenkins the future Labour Chancellor. For good measure the former Conservative Chancellor Rab Butler agreed with them. After the Budget at a lunch Butler suggested demand may have to be expanded further. The NEDC’s concern was that its 4 percent growth target was not realised in 1961 or 1962. It argued therefore that arithmetically if the average 4 per cent target were to be met over the period 1961 to 1966, a higher 5 per cent growth rate was necessary to catch up with the 4 per cent annual target.

Throughout the years of Conservative Government between 1951 and 1964 official Treasury economic forecasts were wrong. Hence Harold Macmillan’s jokes about the official forecast being as useful as using last year’s Bradshaw Railway Timetable. When Maudling gave the economy its powerful stimulus, the forecast implied that the economy was already expanding, but it underestimated the speed of expansion. What the Chancellor had done in the dash for growth was to give an already growing economy a powerful macro-economic pro-cycle stimulus.

1964 was an election year and at its start the economy was growing faster than could be realistically sustained without problems with the balance of payments and the closely related fixed $2.80 Bretton Woods Exchange Rate Parity. In February 1964 the Bank Rate was raised to from 4 to 5 per cent. In his April Budget Speech the Chancellor reported that ‘although last year's budget was described as timid and cautious, it has been followed by an expansion at the annual rate of at least 5 per cent.’ The purpose of the 1964 Budget was ‘to achieve a smooth transition from the recent exceptionally rapid rate of growth to the long-term growth rate of 4 per cent’. Maudling’s judgement was that an increase in taxation of about £100 million should be ‘enough to steady the economy without going so far as to give a definite shock to expansion’.

What was interesting was the response of the official Labour Opposition. Harold Wilson declared that the 1964 Budget was irrelevant to Britain’s problems. Moreover, as the Labour Leader promised, ‘we will deal with this not by monetary methods, not in the main by budgetary methods, but by industrial policy.’ Labour’s analysis was that the problems of balance of payments’ disequilibrium in the context of a fixed exchange rate, could be resolved by an ambitious programme of industrial intervention. It was an approach straight out of the NEDC play book that growth could be raised.

Summary and conclusion

In 1951 Conservative ministers inherited an overheating economy that had to rearm as part of the crisis created by the Korean war. They had a series of challenges and expensive commitments – full employment, the welfare state, the NUS. The economy was no longer a fully functioning market economy but a partially socialised economy with a large, nationalised sector. The Prime. Minister and Chancellor in October 1951 Winston Churchill and Rab Butler had an immediate problem. This was a fixed exchange rate against the dollar without the foreign reserves to manage it, made more awkward by an overheating economy and vulnerable balance payments that could not adjust by a change in the exchange rate. Only a deflation of domestic demand could accomplish that. This set the stage for twenty years of stop-go economic demand management.

Conservative ministers’ attachment to both full employment at a rate lower than Lord Beveridge had suggested would have been satisfactory in the 1940s, created the conditions for permanent excess demand and inflation. This aggravated the structural problems of the labour market. Appeasement of unions over pay made matters worse. Managing these pressures was made more difficult by an expanded public sector, represented by the nationalised industries. A legacy of the thirteen years of Conservative power was toxic industrial relations made worse. Apart from the short episode of Peter Thorneycroft’s tenure at the Treasury, no effective attempt was made to get a purchase on inflation. The intellectual legacy of the Redcliffe Committee that reported in 1959, if anything made matters worse. Eventually both Conservative and Labour governments would have to accept a floating exchange rate, a non-accommodating domestic monetary policy to control inflation, and letting go of a full employment target, as the principal goal of policy in the face of defective labour market institutions.

The establishment of NEDC, its analytical framework and 4 per cent growth target in 1962 was an institutional and intellectual invitation to misadventure. While the Maudling Dash for Growth, with its procyclical stimulus of an already expanding economy that was maintained right up to the general election in October 1964, was a recipe for a balance of payments disequilibrium and pressure on sterling. By neither devaluing or floating sterling Conservative ministers left their Labour successors a next to impossible task given the excess demand in the economy. They had also contributed to a zeitgeist on economic planning where it was naively believed that British industry working with the NEDC could jack up the economic growth rate, by a third more than the Treasury thought realistic. This intellectual legacy could have been calculated to produce a future industrial policy that would ignominiously disappoint.

In answer to the question did Harold Wilson the new Labour Prime Minister and his Chancellor James Callaghan have a more difficult inheritance than Sir Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves in July 2024, the plain answer is yes.

Warwick Lightfoot

28 August 2024

Warwick Lightfoot is an economist and was Special Adviser to the Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1989 to 1992.