China: making sense of the world’s second largest economy – at market exchange rates

Over the last twenty-five years I have tried to understand the development of the Chinese economy, its structure and its implications for the world economy and geopolitical relationships. This has been a difficult task because its economic institutions are opaque. Its economic institutions are opaque. Sorting out where the public sector ends, and the private sector begins is analytically tortuous.

National Peoples Congress: China’s legislature In Tiananmen Square

Last year I went on a protracted visit to Singapore, Taiwan and Japan for some energetic tourism. Taiwan was hugely vibrant and offered a fascinating glimpse of a Chinese culture that had not been transformed by the experiences of radical social reconstruction in the manner of the People's Republic of China, although the protracted martial law of General Chiang Kai-shek and his Nationalist KMT has left its own scars on Taiwanese political culture. As my guide explained when we visited the Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall, Chiang remains a divisive and controversial figure in Taiwan. This visit stimulated an interest in going to mainland China itself.

I spent two and a half weeks as a busy tourist in China travelling from Beijing to Tibet, sailing down the Yangtze River, visiting the Three Gorges Dam and finishing up in Shanghai. This article is my attempt to make sense of what I saw and to set it in the context of what I have read about China, its history and economy. It draws on many economic and financial market presentations I have received, as well as the impressions I have collected from receiving official Chinese delegations on behalf of the Foreign Office and the British Council. The focus of the piece is very much on the Chinese economy. I have tried to match what I know of China from its statistics and analysis of its economic policies and performance, with the intuitive flesh and blood observations that we make in everyday experience.

I travelled to China with an open mind and a determination to treat it as I found it. Some of my observations are completely trite yet no less serious or direct for that. For example: China is very big and has a very big population. As a consequence, China’s domestic economy and its domestic money and capital markets are huge. Things are on a large scale. A population of over 1.4 billion. I was in three cities with 24 million residents. The Beijing metro system is enormous and has scores of lines and hundreds of stations. It is possible to travel on bullet trains for hours on end – four hours from Beijing to Xian and six hours to Shanghai. As a Japanese friend commented to me – in Japan you would end up in the sea.

Out and about China feels very secure and ordered. If you want visible policing in the community, in China, you have it. I managed to lose my wallet on a boat trip down the Huangpu River in Shanghai to see the Bund lit up at night. Within ten minutes of realising I had lost it, the wallet was handed back to me.

China’s Financial Centre in Lights

Simply looking around the parts of China that I visited, which was urban and touristy, my impression is of communities that are prosperous and commercially lively, including Tibet. From the vantage point of the charabanc or railway coach window the Chinese countryside looked more active than rural areas in the East German Landers, parts of rural France and Japan. I swiftly concluded, once I had left Beijing, that the Chinese economy on a purchasing parity basis had to be a lot bigger than the official and international statistics suggest.

I also formed a superficial impression – from the streets around my hotel in Beijing - that household consumption and real household disposable income are significantly repressed. This was drawn from my impression of the housing stock – the blocks of flats I saw and retail offers to consumers that appeared to be available in the shops nearby.

The counterpart to this impression of suppressed private household consumption was the clear national and local political priority given to collective action and investment. This was reflected in the brand new and beautifully presented international airport that I arrived at in Beijing, the high-speed rail connections and railway stations, the regional airports and local authority airlines, motorways and motorway service stations. Even as a casual tourist visiting China for the first time it was not clear that all the infrastructure was warranted. For the tourist it provided a great amenity, but it was not clear what the cost to the community of financing it was or what rate of return it would yield. There were also plenty of examples of China’s distinct investment cycle and the burst property development bubble. This included new buildings standing empty and what appeared to be unfinished construction projects where the developers had given up.

The priority given to the collective management of public space was also reflected in something that surprised me. Throughout China urban business and residential neighbourhoods are carefully planted and very green. This means well managed mature trees, shrubs that need careful horticulture and huge flower beds of roses, bougainvillaea and peonies. What would have been rebarbative concrete urban environments were softened and made attractive by a significant expertise and commitment to arboriculture and horticulture.

The people that I met were open, helpful and patient. In many respects much like the people I had met in Taiwan, but with a much greater language barrier. They were patient with a traveller who was lost, confused and a little bewildered trying to use the metro, bus or cab or having difficulty in finding a particular specialist museum.

Chinese people take a proud interest in their history. This is reflected in their references to China’s various dynasties and different capital cities. Moreover, it is reflected in the sheer numbers of Chinese people who want to see China’s great historical sites, such as the Forbidden City, the Great Wall, the Confucian Temple in Beijing and the Terracotta Army near Xian.

A Group of Communist Party Cadres visit the Confucian Temple in Beijing where for centuries Imperial Mandarins took their examinations

They are also understandably proud of what they have achieved over the last forty-five years and how fortunate they are compared to their parents and grandparents. They will readily refer to their grandparents and parents’ experience of hunger and the past inconvenience of rationing or as they call it the ‘coupon system’. Out and about there is obvious pride taken in China’s new modern navy. Silver gilt models of China’s aircraft carriers are on display in restaurants and hotels in handsome glass cases. They would plainly welcome international appreciation of both China’s history and China’s increasing significance in the contemporary world.

The Chinese economy has been transformed in less than two generations. A socialist planned economy that had been deformed by a sustained effort at socialist command economy planning, the economic misadventure of the Great Leap Forward between 1958 and 1962; and the economic, social and political disasters of Cultural Revolution between 1966 and 1976. Since China’s ten years of chaos, at the end of Mao Zedong life, it has grown from one of poorest countries in the world into being the second biggest economy in the world on using market exchange rates, with per capita incomes placing it in ranks of economies classified by the World Bank as enjoying an upper middle income.

World Bank Measurements of China’s Per Capita GNI: 2000-2017

By any measure this is an impressive economic achievement. Understanding it and what it means for the future of China, the example that it offers other economies and its implications for the wider political economy of the international community remains a fascinating challenge for economists.

Chinese Annual Real GDP Growth: 1979-2018 (Percentage change)

Modern market economy or a directed socialist market economy that’s become the workshop of the world?

Part of this analytical challenge lies in the opacity of Chinese institutions. Scoring the size and scale of the public sector is difficult. It is also difficult to obtain a clear sense of when state direction of resources ends and resources allocated by markets and the price mechanism fully takes over. The superficial impression is that of a socialist economy transformed by its willingness to open the economy to trade, private enterprise and entrepreneurism. The result being a socialist economy replaced by a market economy. This is a misleading gloss on a more prosaic dismantling of China’s socialist planning controls and its pragmatic use of trade and private enterprise within a political economy that continued to be dominated and significantly directed by state policy and economic intervention. This adoption of economic pragmatism could and was easily confused for the adoption of a conventional market or social market economy. In practice China has been a scialist state employing market prices and the incentives of enterprise in the service of a series of specific political goals that emphasised manufacturing and technological development.

Economic pragmatism for socialist political purpose

China’s discovery of economic pragmatism is exemplified by Deng Xiaoping who famously quoted an old proverb that ‘it doesn’t matter whether the cat is black or white, if it catches mice, it is a good cat’. Yet the Chinese state in its five-year plans and policies continued to take an acute interest in the work of its cats and the mice they were choosing to catch.

Deng with his pragmatic cats

Deng with Singapore’s Lee Kwan Ewe whose economic advice he took

By allowing normal prices and market activities from 1982 onwards the Chinese Government greatly improved the everyday functioning of the economy. Its decisions to support export market production, manufacturing investment and infrastructure investment represented an active industrial policy directed at expediting economic growth based on manufacturing output.

Deng Xiaoping China’s poster boy for economic reform

Market pragmatism framed in a Marxist-Leninist dialectic

The strategy for achieving economic reform and development was rooted in a Marxist-Leninist analysis of the sort that led the USSR to embrace the New Economic Policy under Lenin in the 1920s. Deng, like Lenin, in relation to the Soviet Union, argued that China had not sufficiently progressed through a bourgeois capitalist phase of production. It had therefore failed to fully develop its means of production. Deng’s purpose was to develop a socialist market economy. For Deng, 'socialism with Chinese characteristics’ was about having the ‘productive forces’ to achieve prosperity for everyone. His interpretation of the Marxist dialectic was that ‘poor socialism is not socialism’. This interest in pragmatic market socialism by Deng reflected his experience of working and studying in Moscow in the 1920s. He drew on this with impressive facility when he framed his reforms in the context of Marxist-Leninist dialectic. His commitment to industrial development also reflected his early industrial work experience in France in the 1920s, before he went to Moscow, when he worked in the Renault factory and as a fitter at a Le Creuzot factory.

Deng in France in 1920s. Deng in USSR , Moscow 1929

Deng’s pragmatism was illustrated in an interview that he gave to Mike Wallace on 60 Minutes when he explained that he was relaxed about some people and regions being more prosperous, to bring about greater prosperity. Many of the reforms and changes in policy that took place in the early years of China’s economic modernisation were introduced locally. At the start the officials involved risked being sanctioned for being ‘counter-revolutionary’.

Modest local liberal innovation that slowly went national

The first steps towards using markets and prices were made in agriculture where farmers were allowed to sell their own produce. This so-called Household Responsibility System was pioneered in 1978 in Xiaoguang Village after it had experienced a serious drought. Households were made responsible for their own production and were given tools and land in return for fixed output quotas. This novel way of working that defied central state and party policy guidance that had prevailed for more than thirty years, swiftly spread throughout the provinces in Feng yang Xia, Anhui and Sichuan.

In 1980 Deng endorsed the policy which spelt the end of the collective-farm policy. Farmers were freed to sell any surplus or excess yield. Agriculture was used as a model that would later be applied to industrial enterprises that were given the freedom to sell surpluses in addition to the amount already sold to the government under procurement agreements set out in the central plan. Local authorities and industries were given freedom to make their own decisions without detailed direction from Beijing. When local initiates were shown to work, they would then be adopted nationally. Many of China’s reforms were influenced by the example of the Asian Tiger Economies that impressed Deng. Much of the reform agenda was bottom up rather than top down. This process of reform contrasted with the perestroika economic reform initiated by Mikhail Gorbachev in the USSR in the 1980s that was largely top down.

Market structures for a socialist political purpose

China remained a planned economy with its principal economic goals determined and explained through a political process. The economy continued to be planned through central macro-economic management that co-ordinated its political goals. But at a micro-economic level the economy was managed indirectly through market mechanisms, prices and incentives. Local authorities were allowed to invest in industries, and State-Owned Enterprises and they looked to invest the profit was greatest. Deng’s reforms encouraged trade, exports and the development of light industrial manufacturing. Light industry was a good sector for an economy with a limited capital stock to specialise in – it was swift to establish, involved little capital and yielded revenue and foreign exchange reserves that could be used to finance the acquisition and import of technology to facilitate further expansion the industrial base. The capital to finance this investment came from the banking system, not from the state. The profits made by enterprises were reallocated through taxation and banks. Capital was allocated for individual projects by economic agents that were independent from political interference.

A publicly directed banking system that allocates credit to investment

The public sector, state direction and the involvement of the CCP in supervising business executives in the public and private sectors, is central to Chinese economic management. Government intervention in economic policy is proportionate to its political sensitivity. It intervenes more, for example, in commercial banking than in private equity where the direct relationship between the prices of goods and services and households is weaker. Despite significant marketisation and use of prices, China's key industries covering sectors such as infrastructure, telecommunications and finance are owned and managed by the state. There are around 150,000 State Owned Enterprises. They account for over 60 percent of market capitalisation and around two-fifths GDP. The banking system plays a central part in the Chinese public sector’s guidance of its economy. In principle a business or individual could borrow to finance projects outside the state plan, however, in practice 75 per cent of state bank loans go to State Owned Enterprises. Following Deng reforms all capital investment is provided through loans from various state directed financial institutions. Before that investment was financed by grants. These changes left huge scope for political influence over major investment decisions and that political influence was matched by opportunities for rent seeking.

Much of the lending since the reforms is to local authorities and a significant proportion of this has been regarded as non-performing debt for years. A largely publicly owned banking system directs capital and credit to State Owned Enterprises, local authorities and the private sector. Lending priorities and capital allocation reflect the political priorities of the state and the Chinese Communist Party. The surpluses and profits of economic enterprises and market activities are recycled through taxes and dividends. China operates a high savings ratio that it redeploys through the public sector and allocates to government determined priorities such as collective provision of infrastructure, a high-quality public environment in urban communities, manufacturing investment, spending on science and research, police internal security and defence.

China’s Bullet Trains

Three Gorges Yangtze Dam

China’s Electric Power Infrastructure

China’s politically directed, bank financed investment cycle

This potent combination of state direction, entrepreneurial flair and use of market prices has produced a distinctive investment cycle. Conventional market economies exhibit business, credit and economic cycles. China displays an economic cycle that reflects its distinct economic structure. It is an investment cycle driven by changes in the political incentives generated by central policy both in terms of guidance about policy priorities and the availability of credit from the banking system that reflects the evolution of changing political priorities. Local governments, their enterprises and agencies play a major role in the Chinese economy. The officials involved in making the decisions are guided principally by politics. The priority set for them has been to increase recorded GDP in their locality. This has resulted in a series of perverse incentives that stimulate economic activity that in the short term is scored locally as an increase in GDP. Spending on investment and infrastructure has been a significant consequence that directly arises from the political incentives given to the economic agents involved. When credit is available from the banking system and there is encouragement from centrally mandated industrial policies, there is a huge expansion of capital accumulation, until its scale results in bottlenecks, shortages of inputs and price pressures. When these costs result in uncomfortable social pressures, policy is thrown into reverse to ensure social and economic stability. This politically driven investment cycle has resulted in a huge accumulation of manufacturing capital and a very large capital stock in relation to infrastructure. The financial and economic returns on this capital stock are opaque and any assessment in terms of conventional notions of economic efficiency or Paretian optimality would be problematic. This should not be a surprise given that the principal drivers generating this large capital stock are wholly political and remote from conventional concerns about economic welfare.

How big is the Chinese economy and how fast does it grow?

There has been a debate over the last thirty years, resulting in a rich economic literature, about how large the Chinese economy is, how fast it is growing and the extent that official Chinese statistics can be relied on as metrics of economic performance. Some economists have suggested that the official Chinese data has overstated growth, other economists have suggested that the official local data and World Bank data may understate it. The Brookings Institute suggested that between 2008 and 2016 when using value added data it appeared that Chinese growth was overstated by around 1.7 per cent a year, yielding a potential cumulative over statement of output of up to 16 per cent for the period.

Other economists have suggested that the size of Chinese output has not been captured by official data. They include Hunter Clark Maxim Pinkovskiy and Xavier Sala-i-Martin who in a paper China’s Growth May Be Understated published by the NBER in 2017. They used a novel methodology drawing on satellite-recorded nighttime lights, which they suggest offer an unbiased predictor of the economic growth in Chinese cities. Their results are consistent with the Chinese economic growth rate being higher than the statistics that are officially reported. A former Indian IMF economist, Arvind Subramanian, for example, argued in a note for the Petersen Institute in 2011 Is China Already Number One? New GDP Estimates that in Purchasing Power Parity terms the Chinese economy was already bigger than the US economy in 2010, partly because inflation had been overstated, because of insufficient data collection in rural areas. The main conclusion of his analysis was that the level of Chinese GDP tended to be understated in official data while the rate of change of the growth rate was potentially overstated in the context of an underestimate over overall output. He suggested that this suited China – a low reported level of GDP was useful in presentational terms helping China to avoid international financial obligations that may be expensive.

U.S. and Chinese GDP (PPP Basis) as a Share of Global Total: 1980-2018 (Percentage change)

At Purchasing Power Parity is China’s economy much bigger than the latest official data?

At market exchange rates the Chinese economy is the second largest in the world. In terms of assessing an economy’s productive potential and the welfare of its residents it is better to assess what its output amounts to in terms of local spending power, Purchasing Power Parity, is a much better metric. In purchasing parity terms, China has been the world’s largest economy since 2014 on the World Bank data from the IMF, and China was estimated to be bigger than the US economy. The World Bank’s International Comparison program (ICP) assessment in 2017 estimated that China’s PPP GDP was 119 percent of the USA. The World Bank in its recently published ICP data has revised up its PPP GDP estimate of Chinese GDP relative to the USA to 125 percent.

The Chinese National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) expressed caution about this upward revision of estimated Chinese GDP and stressed that China remained a developing economy. There has been a debate over many years about the accuracy and reliability of Chinese official statistics. There have variously been suggestions that data is overstated, conveniently smoothed and modified for purposes of political presentation. The Asia Times in an article commenting on this What’s the real size of China’s economy? by Han Feizi 17 June 2024 explores some of the issues involved. These include China’s reticence about its relative success in terms of international comparisons in case its recognition were to hinder Chinese economic diplomacy in international forums such as the WTO and in awkward bilateral trade relationships with countries such as the US and the EU trading bloc.

What is interesting about Han Feizi’s piece is that it engages directly with the mechanics of how China’s national accounts are constructed. The starting point of the article is that of course China’s economy is at least 25 per cent bigger than that of the US, and the only question is how much larger it is than the figures used to by the World Bank’s estimates of Chinese PPP GDP.

Feizi makes the point vividly: in terms of production China generated twice as much electricity as the US , produced 12.6 times as much steel and 22 times as much cement; its shipyards accounted for over 50 per cent of world output, while US shipbuilding was negligible, China produced 30.2 million cars compared to 10.6 million in the US; and in terms of demand 26 million cars were sold in China compared to 15.5 million sold in the US , Chinese consumers bought 434 million smartphones three times the 144 million sold in the US, Chinese consumers eat twice as much meat and eight times as much seafood as the US and spend twice as much on luxury goods as American shoppers. Feizi notes that these comparisons are not strictly like to like they are volume or unit measurements that need to be adjusted for quality.

Feizi believes that China’s PPP GDP is underestimated as a result of the way that its national accounts are structured and the way that services are scored within them. This measures services consumption as a fraction of US services. Over the last thirty years most OECD economies have introduced the United Nations System of National Accounts (UNSNA). This provides voluntary guidelines on accounting conventions and recognises that national accounts should be constructed to take account of national circumstances. When China made the transition from the Material Product System of scoring the national output of a planned socialist economy to the UN national accounts numeraire in 1985. The MPS did not score the real output of services that were considered as necessary inputs or costs to material production than real value. it estimated services output to be 13 per cent. The World Bank has tried to persuade Chinese statisticians to raise the level of estimated service output. In 2005 China’s National Bureau of Statistics adjusted its estimates of GDP to take better account of services in growth with the result that there is a small increase in the growth rate. Yet the role of services’ output remains low and has neither taken account of the improvement in the quality and range of services or their cost. Feizi’s judgement is that for a sensible estimate of the size of the Chinese economy its PPP GDP needs to be scaled up using the UNSNA accounting conventions by 20 to 40 per cent. He also thinks that realistic price deflators and adjustments for improved quality of services would raise measures of China’s GDP further. This reflects his recent experience travelling in China, buying tech goods, renting cars, staying in boutique hotels and needing to use Chinese private medicine.

Has China’s recent economic success simply returned the world economy to economic normalcy?

In The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Chinese Economic Performance in the Long Run, 960-2030 2007, Angus Maddison catalogues the relative size of the Chinese economy in international economic history. In Maddison’s survey the recent growth in Chinese economic activity represents not so much novelty but a return to China’s more normal importance in world economic history. Maddison estimated that Chinese GDP per capita in 1700 was slightly less than two-thirds of that in Europe, but higher than in Japan or India. He estimated that aggregate GDP growth in China was greater than that in Europe between 1700 and 1820. Maddison therefore calculated that China was the world’s largest economy in 1820, accounting for around a third of world GDP. Europe accounted for 27 per cent of output. Chinese output had grown from 1700, as a result of population growth, but its GDP per capita had fallen back to 55 per cent of the European level. Yet when the industrial revolution took off in the UK and the Netherlands in the early 19th century, China was still the world’s largest economy in terms of overall output..

More than a century of foreign and civil wars, internal strife, weak and ineffective governments, and natural disasters, combined with rapid industrial development in Europe and North America transformed China’s relative economic importance. By the early 1950s China’s share of world output had fallen to a little over 5 per cent and by 1978, after twenty years of socialist planning and revolutionary experiments with economic and social institutions, this ratio had fallen further to 4.9 per cent. The economic reforms initiated by Deng Xiaoping that resulted in rapid Chinese economic growth from 1980 restored China to is position as one of the world’s largest economies. Maddison argued that China has merely returned to its usual place or ranking in the world economy.

Or are Maddison and Chinese Folk memories simply wrong?

Maddison’s estimates would concur with traditional Chinese folk memory that believes that China’s economy was the largest and most prosperous in the world five hundred years ago. Some Chinese economists, however, think that Maddison may have overestimated the historic size of the Chinese economy in relation to the rest of the world. For example, David Daokui Li comments in his book China’s World View on this popular belief in China’s historic prosperity. He and Guan Hanhui estimated Chinese GDP from historical records of output data to construct GDP for China’s dynasties. They applied national accounting analysis to Ming data. They found that per capita GDP growth was stagnant in the Ming Dynasty, running at half Maddison’s estimate. Indeed, this economic analysis of the Ming era suggested that China had entered into a sort of textbook Malthusian trap where population growth was faster than the increase in the supply of food. This resulted in periodic famine, war and epidemics between 1620's and 1640’s.

Li and Hanhui’s work suggests that per capita income had started to decline in the Song Dynasty. Between 980 and 1840 total output rose at a rate of 0.35 percent while the population grew at a much faster rate. The result was that there was a ‘chronic decline in per capita GDP extreme poverty and a surplus of agricultural labour’. By their calculations by 1775 China’s per capita income was only 30 percent of the UK. In these circumstances ‘there was no way for China to have developed its own industrial base, since labour was so abundant that it did not allow for the intervention of labour-saving technologies’. Daokui Li argues that Maddison’s method of multiplying what was a guess of per capita national income by the size of the population yielded highly misleading results about China’s place in the world economy in the early decades of the 19th century. In many respects if Daokui Li and Guan Hanhui are corrected, the recent Chinese economic achievement is even greater in historical terms. There is an extensive economic history literature that explores these issues that Richard von Glahn examined in his book The Economic History of China from Antiquity to the Nineteenth Century. Having taken account of the practical difficulties of estimating output and incomes and the largely recondite or heuristic character of the exercise von Glahn concluded that Liu Tis estimates for late Imperial Chinese output offer the best approximation of Chinese GDP per capita and its trend. Between 1600 and 1750 it fell by 12 per cent and then fell again by over 6 per cent between 1750 and 1840. A cumulative fall of close to a fifth.

How fast will an over accumulation of capital be corrected?

The Chinese growth has been driven by investment, facilitated by a very high household and corporate savings ratio, directed at an export orientated expansion of manufacturing drawing on the examples of Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan. In the process consumption has been repressed and there is an overaccumulation of capital both in terms of manufacturing capacity and underused infrastructure. This over large capital stock exhibits low rates of return that do not match the financial and real resource costs of its acquisition. Unwinding the consequences of this misallocation of resources would in any economy be awkward. It involves either a swift adjustment that involves a short shock to output, employment and prices where after a process of Schumpeterian creative destruction bankrupt enterprises are swiftly and ruthlessly reorganised to make the path clear for a renewed process of accumulation. This has tended to be the path of adjustment made in Anglo-Saxon economies such as the UK and the US in the inter-war years of the 20th century and early 1980s. The alternative is a very slow protracted adjustment. The classic example of this is Japan over the last thirty years.

Paternalist government with insufficient hard budget constraints

Janos Kornai, the Hungarian economist who studied command economies, noted that in socialist economies, policy makers were reluctant to take social and political risks in correcting economic mistakes. As a result, there are few hard budget constraints and when they are applied the action is tardy and hesitant. Kornai described this as a ‘paternalistic government’. China’s economic priority is stability. The purpose of economic reform was framed by Deng Xiaoping at its start; prosperity was to make China’s socialist society, led by the CCP, more secure. Necessary uncomfortable adjustment to deal with accumulating economic challenges is not part of this political and economic stability reflex that is entrenched in the Chinese official political economy. This is reflected in things like official intervention to control pork costs given the political sensitivity surrounding food prices, attempts to stabilise equity prices, the management of China’s indebted and problematic property market and the sensitivity surrounding youth unemployment data. In the political economy of the CCP awkward and uncomfortable adjustment is managed, delayed and necessary adjustment is slow.

China has been hugely successful in creating a higher middle-income economy over the last forty-five years. The preferred route of market socialism has reaped immense benefits. Yet it has slowly come up against the economic constraints that arise from an economy largely directed by a state public sector. The emphasis on rapid capital accumulation and investment in infrastructure has created a capital stock with low rates of return, industrial sectors that exhibit over capacity both in relation to Chinese and international markets and the repression of household consumption.

The repression of household income and consumption is an artefact of state policy

Over more than forty years the combination of public sector priority being given to investment, manufacturing capacity and exports, reflected in protracted episodes where the renminbi was undervalued on international markets, was to promote investment and production over consumption and the economic welfare of domestic Chinese households. Household income was repressed by weaker wage growth than China’s economic success would normally have been expected to generate. Relatively weak wages and growth in household disposable income has been the product of labour market institutions carefully designed to contain the growth in domestic production costs. These artefacts of the modern Chinese economy have not been created by accident but through sustained policy choices.

There is an economic price of lost efficiency and lower economic welfare for consumers, for China’s political decisions to give priority to investment

A feature of non-market economic practice is the practical difficulty of optimising the use of resources and reallocating labour and capital to more productive uses. Economic efficiency in China has suffered from the lack of a hard budget constraint. The state dominated banking system has offered soft finance that vitiates any conventional notion of the discipline of bankruptcy and insolvency procedures and practice. These instruments are largely lacking in China and when they operate, they are significantly blunted in their effects. In all social and political systems there is huge enthusiasm for new projects and investment in new capital, but sorting out things that go wrong and shutting down dud projects stimulates much less enthusiasm. Where there is public intervention in the economy this political guidance makes the recognition and managing its consequences slower and more difficult. The processes of Schumpeterian creative destruction are blunted.

It is generally agreed by economists looking at China from the outside that its investment export oriented growth model based on artificially high savings and artificially low household consumption has run its course. Chinese wage costs have risen compared to other emerging market economies and even relative to the US. The combination of the previous one child family planning policy and rising prosperity have influenced China’s demography. This will mean an older society and a potential fall in the population during the 21st century. China does not have a flexible labour market. Regulation constrains regional migration, by a system of rules that limit the access of people who move to public services, such as health and schools, in their new location. This limits the mobility of labour as a factor of production and by obliging workers who do move effect to provide for things such as their own health care to maintain a higher levels of savings than they would otherwise need. That further aggravates household saving. While overcapacity and inefficient capital accumulation contributes to slower productivity growth.

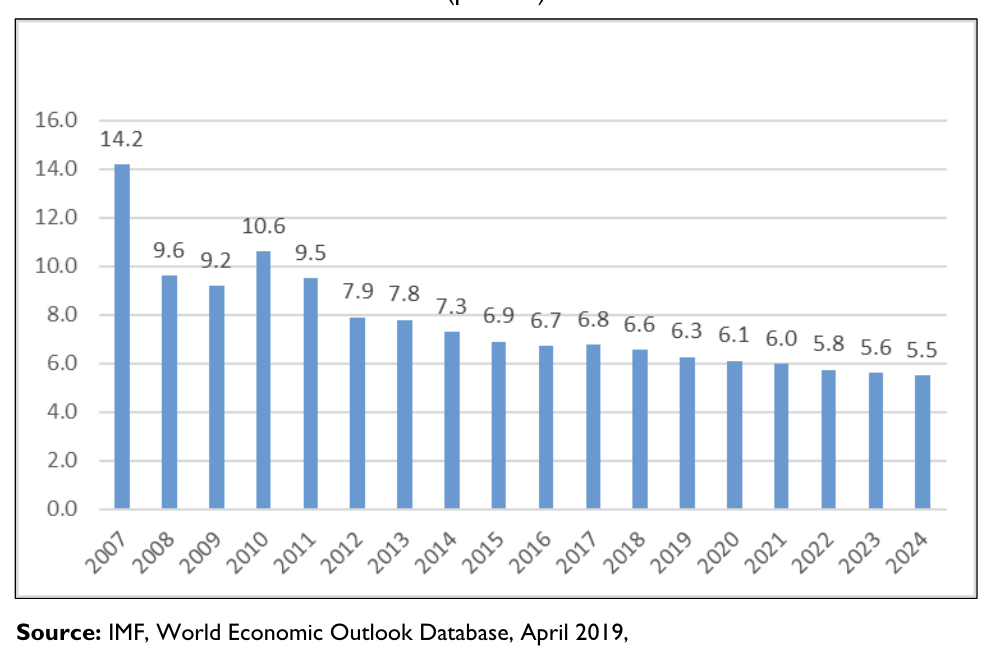

China’s Real Annual GDP Growth: 2007-2018 and Projections through 202 (Percentage change)

These factors will combine to slow the future growth of the Chinese economy. The years of very high growth averaging 9 per cent a year are therefore over. Annual growth is now projected to be 5 per cent or less. For twenty years China, has exhibited as Dwight Perkins put it in The Challenges of China’s Growth, a ‘trade ratio as a share of GDP’ that is ‘extraordinarily high for such a large country’. Future sustained growth in China will have to come from increases in aggregate domestic demand and from greater opportunities being given to households to consume. This results in an exaggerated discussion about the problems of the Chinese economy and China’s wider political future. A much slower rate of growth will be applied to an economy that on more realistic purchasing power parity estimates than those reported in official statistics is probably 30 per cent or bigger than the latest estimates. A slower rate of growth applied to a very large economy will result in an economy that in absolute terms continues to be of increasing importance in the international economy.

China’s economy will continue to grow because of its internal market

China’s economy will continue to grow. Whatever cyclical and structural impediments may hinder it, the size of its natural home internal market and the scale of its science and technology base will ensure future expansion. The economic histories of the US after the Civil War and Germany after unification in 1870 offer potent examples of the benefits that accrue from a large unified internal market. In China’s case with its much greater population the effect will be greater. David Daokui Li in China’s WorldView regards the growth of China’s economy and it, overtaking the US at market exchange rates as the world’s largest economy, as inevitable. He considers the projection that it will happen in 2035 as ‘a conservative forecast’.

Science with Chinese essence: a huge capacity to translate applied R&D into price competitive marketable products

Chinese science and research are approaching that of the US in terms of its scale and quality. This is reflected in the number of papers China publishes, the patents it registers and the perceived improvement in Chinese universities. From a society that had profound problems with literacy eighty years ago, problems that were aggravated by the difficulties of the Mandarin script, China today has a non graduate workforce that is probably better qualified than its American counterpart. China moreover has shown much greater facility for translating novel science and technology into practical goods delivered at competitive prices, such as solar panels and electric motor vehicles.

Xian Car Showroom: taking technology and translating it into competitively priced products

Policymakers in the Biden administration presiding over its Inflation Reduction Act network of industrial subsidies or in the European Union’s Commission trying to get practical results out of the Horizon science programme would give their eye teeth for the kind of Science, R&D, Military, Industrial Complex that China has. In terms of AI and digital innovation China has distinct opportunities that arise from the size of its population and the scale of its economy.

Relative progress on AI will turn the number of engineers, the computer capacity and data a country has. world view David Daokui Li in his recent book points out that China has the world’s largest cohort of engineers. It graduates 4.4 million new engineers every year, which is about the total as the number of engineers that work in the US. China has the second largest reserves of computer power following the US. Connected computers can accomplish the work of a small number of superfast computers. In terms of data China benefits from the world’s largest population of internet users that generates a huge amount of data for machine learning. Everyday use of digital payments systems on phones such as Alipay is more ubiquitous than in the UK and certainly more present than in countries such as Germany or Japan. Moreover, there are more everyday opportunities where people in China have to present their non-financial data, such as identity card information on public transport at railway stations, visiting museums and controlled public spaces.

Most economies go through adverse cycle and exhibit structural impediments

The combination of a huge population, an improving stock of human capital in terms of quality and an already large industrial capability supported by a massive science base will ensure that the Chinese economy will continue to grow and adapt. How fast it grows and how much progress is made in terms of conventional economic welfare will depend on the policy of the Chinese Government. And that will turn on the extent it is prepared to make full use of conventional market signals and disciplines and the willingness that it has to apply hard budget constraints of projects that are encouraged, sanctioned and financed in one way or another by the public sector. An investment cycle that has gone wrong, a property boom that has run its course and a banking and state enterprise sector that is over indebted, is not a recipe for an irrecoverable economic disaster or permanent stagnation. On that criteria most of the advanced market economies that have prospered over the last 150 years would have failed decades ago. Moreover, China has plenty of opportunities to raise productivity, improve economic welfare and efficiency by reforming its banking and credit markets, reducing rent seeking, developing realistically hard budget constraints and improving its bankruptcy, insolvency and commercial re-organisation procedures.

The opportunity to raise economic growth through banking and financial reform

There is no doubt that China has long standing problems of bad debt, defective corporate governance, rent seeking and commercial bank balance sheets that have plainly needed cleaning up for many years. At any given time, it is not clear what ratio of commercial debt should be scored as bad debt or non-performing debt.

The Congress Research Service paper China’s Economy: Current Trends and Issues, September 2023 illustrates the potential scale of China’s debt challenges. China’s total non-financial debt—household, corporate, and Government reached 297 per cent of GDP in 2022. Most of the debt is reported as being held by private firms and provincial and local governments. In terms of efficient allocation of credit and capital, Chinese banks have a long history of channelling their lending into either state owned or state-controlled enterprises, because this is perceived as politically safe, even if the lending may not be commercially safe.

Nonfinancial Debt as Share of China’s GDP

This has changed to some degree but there needs to be a radical change in regulation, culture and political practice for China to get a banking sector that can efficiently support a conventionally growing economy. These defective financial and other legal institutions hinder the Chinese economy. Yet it offers China an opportunity to raise its future productivity growth. As Dwight Perkins argued in his essay if the Chinese financial system were put at ‘the service of the whole economy, not just the favoured state sector, China could achieve large efficiency gains’. Given what China has achieved with a defective banking system and weak institutions, it should perform better if it properly reforms and effectively reduces political interference with lending and credit allocation. This is an opportunity for the future.

The geopolitical role of China lies in its capacity to create material

In terms of the wider political economy of the world and its geopolitics, China's science base and industrial capacity will be central to its role. The capacity to innovate and produce competitively combined with a manufacturing capacity that accounts for around 35 per cent of world industrial output will determine China’s relative geopolitical influence. Whether China’s future international financial status will match its science base and manufacturing strength is less clear.

China’s industrial output sails down the Yangtze River

China’s future international financial status?

That will require international confidence in the financial integrity of China’s financial markets and institutions as well as having an open and transparent judicial system for sorting out rows when things go wrong. For a financial status that matches China’s overall economic role, international rentiers will have to be confident that when there is a row they will be treated fairly. If they have a financial claim on an asset, it should be enforceable. Where there are genuine losses, they should be apportioned fairly between Chinese interests and those of foreign investors. The international financial community will for example pay careful attention to see how the present problems in the property market are sorted out and how mindful Chinese authorities are about protecting the interests of foreign investors. Chinese investors whether they are private individuals or corporations appear to be anxious to get assets out of China. International investors would be more likely to use financial instruments in China if there was an emerging organic confidence in them exhibited by their Chinese counterparts, freely choosing to exhibit an element of home bias without any policy pressure on them.

Warwick Lightfoot

26 June 2024

Warwick Lightfoot is an economist and was Special Adviser to the Chancellor of the Exchequer from1989 to1992.