British House of Lords challenges Central Banks' groupthink, record and defective modelling

25 years of independence raise awkward questions about the Bank of England and HM Treasury’s record

Central banks in advanced economies since the 1990s have enjoyed great discretion, policy independence and much analytical deference. Yet the economies whose monetary policies and macro-economics they have done so much to shape have exhibited shocks and instability in the first two decades of the 21 century that are significantly accounted for by the policy choices made by central banks that have been invested with huge policy making power and intellectual authority.

How well are modern central banks doing their job?

The time has come to interrogate their collective record, what they have got right and where things have gone wrong. This should involve an exploration of their institutional position, their personnel, their operating procedures, the economic frameworks that they have constructed to inform their conduct and several of the tropes about monetary and fiscal policy that have informed the institutional division of labour between finance ministries and central banks since the 1990s.

It is a fair observation to say that elected politicians, economists working in academia and the serious scholarly commenting world of think tanks and journalism have been reticent of interrogating central banks on their record, the intellectual framework they apply in forming policy and whether the present assignment of functions and policy instruments within macro-economic policy is appropriate or optimal.

Lords’ Economic Affairs Committee breaks the omerta of deference to central banks

The British House of Lords Economic Affairs Committee offers an interesting example of a serious and authoritative body that has broken the omerta of universal deference to central bank authority by asking some appropriately awkward question about the Bank of England, in particular and the wider international consensus among central banks that the famous Old Lady has broadly conformed to. The Economic Affairs Committee of the Lords Making an independent Bank of England work better published on 27 November 2023 builds on previous work done by the Committee exploring the awkward consequences and clumsy character of the Bank of England’s protracted programme of quantitative easing which expanded the central bank’s balance sheet from 5 per cent to 50 percent of GDP.

That report Quantitative easing: a dangerous addiction? published on 16 July 2021 recognised that while QE had been effective in stabilising financial markets during episodes of financial and economic crisis, it had a ‘limited impact on growth and aggregate demand’ in the ten years to 2021 and there was little evidence to suggest that QE increased bank lending, investment, or that it had stimulated consumer spending of owners of financial assets , through so called asset price effects. The Lords’ report moreover draws attention to the view there was a generally held perception that the British central bank used QE ‘to finance the Government’s deficit during the COVID-19 pandemic’. The Bank of England effectively chose to monetize the Government’s deficit. As the report notes ‘The Bank’s bond purchases were aligned closely with the speed of issuance by HM Treasury.’

Examining Bank of England’s record twenty-five years on from operational independence

In Making an independent Bank of England work better the Lords expand their criticism of the Bank of England. The report marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of the 1998 Bank of England Act which provides the legal structure for the UK central bank’s operational independence. The conclusions of the report are predicated on the benefits of an institutionally independent central bank. The Lords consider that a central bank free of political independence is considered to be a major contributor to stable inflation and stable expectations about inflation.

The shared collective policy folly of the international central bank fraternity

Despite this support the Lords Economic Affairs Committee did not pull its punches about the Bank’s contribution to what it describes as ‘the high and persistent inflation since 2021’. While adverse post covid 19 supply shocks and the economic effects of the Russian invasion of Ukraine account for some of the inflation persistent above target ,inflation since 2021 reflects errors in the conduct of monetary policy, the report particularly identifies over reliance on ‘inadequate forecasting models’.

The Lords’ report suggests that these failures by the British central bank were shared by the wider international central banking community. Among central bankers there was complacency about inflation. They failed to see high and persistent inflation. Central banks, their economists and their acolytes working in universities and in financial markets concentrated the supply-side character of the inflationary shocks and ignored the monetary shocks that had arisen from their own preferred policy tools.

Annual percentage change in CPI (UK, Eurozone, France, Japan and US)

The embedded inflation that they had created was described by central banks as ‘transitory’. Moreover, they persisted in this judgement when it was clear that the inflation problem of the advanced economies that they served were anything but transitory and dogmatically persisted with their approach when, as Lawrence Summers the former US Treasury Secretary and a critic of central bank policy myopia, said it was time for ‘team transitory to step aside’. The Lords’ report identifies a culture of ‘groupthink’ in the Bank of England and among the international central banking community. This is exemplified by the lack of curiosity that modern central bankers have about monetary economics and the measurement and role of money in the economy.

Lords’ report’s recommendations

The recommendations made by the Lords in Making an independent Bank of England work better are sensible and deserve careful consideration and should be implemented. They focus on narrowing the central bank’s expanding remit. The Lords consider the recently widened remit ‘risks jeopardising’ the central bank’s primary objective and increases the potential for conflict between its different functions and objectives. To address the narrow intellectual and policy culture that the Lords considers to have contributed to the errors made in the conduct of monetary policy by the wider central banking community, there should be a review of and change in governance, hiring practices and appointments especially of the Monetary Policy Committee the MPC.

The Lords also argue that the Bank of England should be properly held to account. The report considers that the Government is unable to challenge Bank decisions without compromising its independence. They therefore consider it ‘imperative that the Bank and its remit are effectively scrutinised by, and its own officials are held accountable to, Parliament. Report therefore suggests that ‘Parliament should conduct an overarching review of the Bank and its remit, performance and operations.’ In the Lords’ judgement ‘a democratic deficit has emerged, which risks undermining confidence in the Bank and its operational independence. The report also makes some interesting recommendations about the interaction of fiscal and monetary decisions and the interaction between monetary policy and debt management. Among these the Lords Economic Affairs Committee repeats its request that the Deed of Indemnity between the Bank and HM Treasury which commits the taxpayer to cover any financial losses made by the Bank arising out of the QE programme, should be published.

An egregious merit of the Lord’s report: direct engagement with the issues and lucidity

The Lords report has the great merit of being direct in its interrogation of the issues involved and in identifying matters that need to be remedied. It also benefits from being drafted in a clear and cogent style that manages to avoid elisions of meaning and ambiguity. In the present culture of British public policy making the report is therefore egregious. It offers a sharp contrast of lucid analysis and clear recommendation.

Chronic policy error invites a more radical interrogation of the institutions involved

The failures of the Bank of England and the Treasury in macro-economic management in the first decades of the 21st century, however, invite a more radical interrogation than that so far pursued by the Lords’ Economic Affairs Committee. In many respects these questions relate to genuinely difficult matters such as the extent that monetary and fiscal policy can be carried out separately by separate institutions – central banks and finance ministries. In the specific British circumstance of the Bank of England there are, however, more awkward questions that turn on its institutional and intellectual heritage as a central bank. These invite anxiety about its institutional capability.

Why central banks and inflation targeting warrant a more radical interrogation

The first big question that needs to be explored is the inflation target itself. Some form of inflation target is now pursued by most central banks. Its merit is that as a policy objective it focuses on the ultimate goal of monetary policy, a rough approximation of price stability. Its difficulty is that it is one thing to have an inflation target but another thing to explain the analytical framework and policies needed to meet it. Inflation is moreover a lagging indicator. Policy makers may already have trouble on their hands, cooked into the economy, when they become properly aware of it in rising price indices. Hence Alan Greenspan’s comment that using an inflation target is like driving the car using the rear-view mirror. It was to overcome this problem that central banks matched their inflation targets with forward looking economic forecasts to ensure that they acted to pre-empt inflation. These forecasts have proved to be defective.

The second question is what do the deficiencies of economic modelling , forecasting and analysis imply for the practicality of inflation targeting? The models have not worked. Moreover the framing of policy decisions around data to identify appropriate monetary conditions in terms of where the level of economic activity is in relation to its long-term trend rate of non-inflationary growth and the difference between the two, the output gap, has resulted in practical central bank decisions on interest rates turning on three unknowable things – where precisely an economy is in the economic cycle, the trend rate of growth and the output gap. What may have an interesting coherence in an academic Keynesian orientated seminar room, is little or no help in practical policy making. The Lords’ committee rightly draws attention to deficiencies in forecasting and analysis in central banks, however this intellectual approach has become endemic in the framing of operating inflation targeting regimes and invites radical questions about the character and operability of inflation targets themselves.

The third question relates to the need to rehabilitate the role of fiscal policy as a source of economic stimulus when monetary policy loses traction. In 2008 the IMF internationally brought active fiscal policy back to life at the start of the Great Recession. Fiscal stimulus measures across the world, led by the Obama administration in the US, stabilised economies after the monetary shock of the collapse of credit markets and banks. Yet after 2010, policy makers returned to monetary policy instruments to try and stimulate output. The results were disappointing. The House of Lords Economic Affairs Committee has drawn attention to this disappointment in its analysis of QE. An atmosphere of stasis, stationary states and secular stagnation enveloped advanced economies until 2020. Policy makers should have been using active fiscal policies to support economic activity in that decade, instead they tried to get the dead horse of monetary policy to race. The strong response of advanced economies to the stimulus measures taken in response by advanced economies, led by the Trump administrations fiscal stimulus packages, demonstrate the power that fiscal policy can exert. Janet Yellen the former Chair of the Federal Reserve Board was right when she said in 2020 that fiscal policy had an important role to play as a source of stimulus and that if there were an inflation problem central banks had the tools to deal with it. The problem was not the necessary stimulus, but the reticence exhibited by central banks in using their monetary policy tools to deal with the inflation that began to present itself. They took tardy baby steps in tightening monetary conditions and raising interest rates.

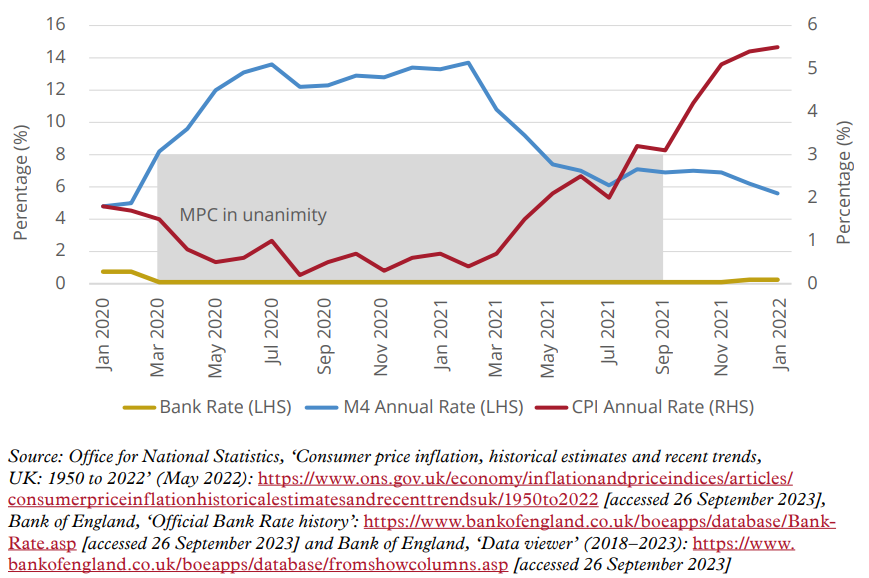

UK bank rate versus CPI and M4: January 2020 to January 2022

Awkward need to probe the effectiveness of the Bank of England and HM Treasury

The awkward specific British questions relate to the institutional capacity of the Bank of England as a central bank and HM Treasury as a finance ministry in relation to framing monetary policy for the central bank and the macro-economic management of the economy. When Norman Lamont, in his resignation statement as Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1993, followed Nigel Lawson in calling for the central bank to be made independent, there was a lot to be said for it.

Rationale for central bank independence

A central bank can deliver a monetary stimulus that will raise output, employment and income in the short term without much impact on prices. Given the neutrality of money in the long term such a stimulus runs off and is simply reflected in a higher price level with no overall increase in economic welfare. Governments facing their electorates with election timetables that do not neatly match economic cycles may be tempted to take risks with price stability for short term political gain. It is, therefore, better to remove this temptation and make the central bank independent.

While there was great merit in this there were equally merits in exploring the uncomfortable question of whether policy makers should make this central bank, the Bank of England, independent. The Bank of England had, for example, insisted for decades on using a set of anachronistic institutions – Discount Houses – specialist bill brokers to carry out its open market operations in the money market when they no longer had a proper function in the London money market dominated by the big commercial clearing banks and the international banks. A clumsy manoeuvre in the Discount Market managed a lack of money market liquidity in the summer of 1992 arguably ignited the foreign exchange markets to test whether the UK authorities had the resolve to defend sterling within the ERM.

At the heart of these serial mistakes are three things: a confident conceit that each iteration of policy is beyond interrogation, no less than improvement; a reluctance to consider the role of money in the economy; and an asymmetry in the approach to the risk of inflation as opposed to short episodes when the economy may be expanding below its trend rate of growth.

Why look into the crystal ball when you can read the book? – the UK authorities record

Both the Treasury and the Bank of England have long and poor histories in terms of inflation control and macro-economic management. In the fifty-three years since 1970 the joint stewardship of what used to be quaintly called the ‘authorities’ – the Treasury and Bank of England could best be described as ‘continuity monetary shambles.’ The list of episodes that earn the authorities this indictment is extensive: Competition and Credit in 1971; the response for the ending of the Bretton Woods exchange rate regime; the Barber Boom; counter inflation policy based on prices and incomes policy in the 1960s and 1970s; the reflationary response to the oil price shock in 1973; inflation at 25 per cent in 1975; attempting to cap sterling in 1977 as the exchange rate adjusted to the impact of North Sea oil on the balance of payments; the Lawson boom; the ERM debacle; the loose monetary conditions that led up to the financial market crises between 2007 and 2009; the inappropriate use of QE between 2010 and 2020; and the inflation that the UK has had since 2021. In a criminal proceeding, legal defence counsel in making a plea of mitigation before sentencing, would have to draw a tribunal’s attention to a lengthy list of offences that ought to be taken into account.

While the rationale for an independent central bank is strong the Bank of England exhibits long standing institutional weaknesses that vitiate it. As one retired senior member of the Government Economic Service has noted ‘I've always been intellectually convinced by the argument that Central Banks should be independent. Nevertheless, the only time when there was enough grip to use monetary policy to control inflation was in the early 1980s when the Bank wasn't independent’. The same ministers then lost control of inflation between 1985 and 1989 in the Lawson boom; and they again properly gripped monetary policy by putting interest rates up to 15 per cent to disinflate the economy in October 1989.

Since 1998, monetary policy and pretty much the whole of macro-economic management has been framed around the central bank’s inflation target set by the Treasury. The official Treasury then appoints the personnel that run the Bank of England – Governors, Deputy Governors and members of the MPC to its taste. There is then a feedback loop where having framed the Bank of England’s target and appointed the people to carry it out, both the Treasury and the Bank of England insist on great deference to the central bank’s independence. That places this cosy policy nexus beyond effective public political oversight, and little scrutiny outside the Treasury canteen.

Warwick Lightfoot

11 December 2023

Warwick Lightfoot is an economist and was Special Adviser to the Chancellor of the Exchequer between 1989 and 1992.