Are British Taxpayers saving up to pay future taxes?

Is the British economy exhibiting neo-Ricardian Equivalence responding both to public debt and public spending?

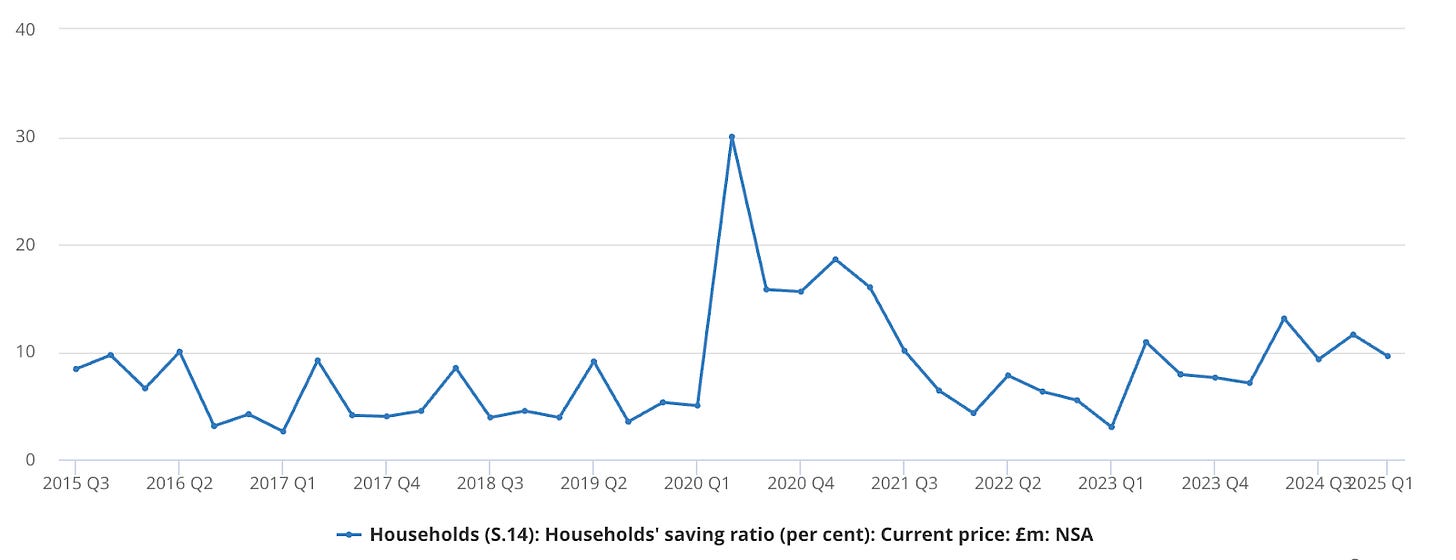

The UK savings ratio remains high. It rose sharply to 30 per cent during the Covid public health emergency when peoples’ incomes were protected and their normal opportunities to consume were constrained and it remained elevated when households braced themselves for elevated energy bills resulting from the Ukrainian war. Yet the savings ratio has remained high at around 10 per cent, in the first quarter of 2025 it was reported by the ONS to be 9.6 per cent. Could it be that British households are saving up to finance expected future tax increases?

UK Households’ Savings Ratio

Source ONS 30 June 2025

Long-standing official neuroses about low rates of British household saving

Traditionally the UK has tended to have a relatively low rate of household savings. The UK is a consumption oriented economy with consumer spending accounting for a high ratio of expenditure in GDP. High consumption is mirrored in lower investment and a low savings ratio. The low savings ratio results in periodic hand wringing from the British authorities. Good examples are offered by the Bank of England and H M Treasury which offer periodic official homilies about the need to raise savings. These have included the Helping People To Save, a paper published by HM Treasury, March 2001. This reflected the concerns expressed in an article in the Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin published in Spring 2001 that noted a two thirds decline in the UK’s ratio between 1997 and 2001.

This sustained official anxiety about low savings has been reflected in a series of official initiatives over the last thirty-five years directed at increasing savings. Among them the introduction of Individual Savings Accounts - Isas, stakeholder and auto enrolled pensions, making savings products more accessible through CAT standards promoting transparency and helping people to save who do not have current or checking bank accounts. I was directly involved in the introduction of one of these initiatives. This was the launch of the Tax-exempt Special Savings Accounts - Tessas - in the 1990 Budget for Saving, presented by John Major. And I still have my, now matured, Tessa savings account at the Skipton Building Society.

The Unexpected High UK Saving Ratio that Puzzled Economists in the 1970s

So an episode where the UK savings ratio is unusually high invites interest and is worthy of some thought and investigation. In the mid-1970s, for example, there was a sharp jump in the savings ratio that surprised economists. The savings ratio rose from 3.4 per cent at the start of 1971 to 10 per cent in the first quarter of 1975. The increase in savings coincided with a sharp acceleration in the rate of inflation. This puzzled economists. The working assumption was that economic agents would not save when their real incomes were being eroded and the real value of cash holding was being reduced by inflation.

The Deputy Governor tried to explain it

The unexpected changes in the behaviour of economic agents took the central bank by surprise. A surprise amply illustrated by a lecture delivered by the Deputy Governor of the Bank of England Sir Kit McMahon to the Institute of Bankers in January 1981. ‘It is striking to recall just how large the shifts in sectoral financial balances have been. Taking the personal sector, for example, the surplus in the 1960s and early 1970s averaged around 2 percent of GDP, whereas from 1973 onwards the average has been over 5 per cent.. This shift in the personal sector was necessarily matched by bigger deficits elsewhere - especially for the public sector and for industrial companies’.

‘I should, however, like to make one general point, perhaps particularly well illustrated by the rise in the personal savings ratio. It is salutary to remember that the reaction of individuals to inflation and uncertainty was not predicted, and still cannot claim to be fully understood. One explanation ascribes the increased flow of new saving to an attempt on the part of individuals to make good the erosion, by inflation, of the real value of their financial assets.

‘It is striking that a large part of the personal sector's increased saving went into liquid assets. Besides a desire to maintain the real value of transactions balances, another factor was no doubt an unwillingness, in a period of increased uncertainty, to commit funds to longer-term financial assets. A shift in income distribution in favour of wage earners may also have played a part, since bank accounts and building society deposits are the most accessible and familiar ways of saving for this group’.

‘During the 1970s, personal sector deposits with building societies more than quadrupled, rising from £10 billion to over £40 billion; in the same period, deposits with banks rose only threefold, from about the same initial level of £ 10 billion to just over £30 billion’.

At the time a series of articles appeared in the then specialist non-academic economic press principally publications sponsored by the then great London Clearing Banks, such as the Three Banks Review which had a go at analysing what had happened. There was no clear explanation for the change in savings behaviour but the most plausible explanation was that people needed significantly higher precautionary savings balances to manage a series of unexpectedly higher bills. These unexpectedly higher bills were generated by higher utility bills, higher oil prices after the Middle East War in 1973. A further source of high unplanned bills was generated by higher domestic rate bills - a local property tax based on the imputed rental income of a residence - levied by new local authorities created by the reorganisation of local government in 1973. These rate bills were so unpopular that the Wilson Labour Government set up an inquiry into local authority finance chaired by Sir Frank Layfield QC, which reported in 1976 and proposed the replacement of the rating system.

Robert Barro and Neo-Ricardian Equivalence

By chance in the mid-1970s Robert Barro, a Harvard economist who at that time was working at Chicago University developed a highly theoretical explanation for changes in household savings that was both arresting and provocative. He set this out in an article Are Government Bonds Net Wealth? in Journal of Political Economy in December 1974. This broadly suggests that if economic agents see their government borrowing money by issuing bonds, they will adjust their behaviour by raising their savings to be able to pay for the future taxes that will be needed to service the higher prospective government debt charges. Robert Barro’s article was important in helping economists incorporate thinking about the expectations of economic agents in changing their behaviour and the rich branch of economic theory associated with rational expectations and new classical economics associated with university economic departments located in the America mid-west and on the shore of the Great Lakes, the so-called freshwater school of thinking.

Barro’s proposition posed an immediate challenge to standard Keynesian macro-economic policy. In short, Keynesian macro policy believed it desirable and possible to smooth the economic cycle by offsetting private sector losses of demand by active fiscal policy and running budget deficits. Barro suggested this active fiscal policy would be vitiated , if the stimulus effects of public deficits on demand are offset by forward looking private households increasing savings.

Several intellectual friends of Robert Barro, such as James Buchanan pointed out that his proposition was not a new idea. It could be identified as having been explored in the work of the classical economists such as principally David Ricardo but also Adam Smith. Ricardo had touched on the ideas in his Principles of Taxation in 1817 and further developed them in his Essay on the Funding System in 1820. David Ricardo was sceptical about the practical possibility of economic agents taking account of future taxation in their behaviour and assumed that they would take a myopic approach to future tax burdens. As the debate surrounding Robert Barro article took off, his theoretical proposition, was however swiftly christened Neo-Ricardian Equivalence

Part of what provoked economists were the series of highly stylised facts that informed the Neo-Ricardian Equivalence as he formulated it. Among these were information about the future course of government bond issuance and the suggestion that households had long-international time horizons that meant that they would be concerned to-day about bills that pay come in thirty or forty years. This long time horizon was generated by assumptions about altruism and a powerful bequests motive that people have for their children and grandchildren. This in turn came from Robert Barro’s conversations with a Chicago colleague Gary Becker. Gary Becker had applied conventional neo-classical marginalist analysis to things, such as education and training, sex and race discrimination and fertility. Out of these conversations came Robert Barro’s suggestion that economic agents may be motivated to see beyond their own lifetimes and change their behaviour to ensure the economic welfare of people they care for.

Fiscal policy was discarded as a practical instrument of economic demand management

Neo-Ricardian Equivalence provoked a stimulating debate about economic behaviour, expectations and the future conduct of monetary and fiscal policy. While its narrow analytical construction may have been considered brittle and fanciful there is no doubting the influence it had on both central banks and finance ministries in framing macro-economic demand management between the 1980 and and the credit crunch and the Great Economic Crisis in 2008. Active use of fiscal policy to manage demand was pretty much abandoned. The emphasis was placed on the economy being managed by independent central banks through changes in monetary conditions principally using interest rates to meet an inflation objective.

Most of the interest in fiscal policy switched to focusing on the sustainability and prudent management of government deficits and the stock of government debt, rather than the role of government borrowing in stabilising output and the economic cycle. This found its most complete expression in the European Union's Growth and Stability Pact constructed in the approach to the construction of the Euro in 1999. This set rules for deficits of no more than 3 per cent and a stock of public debt of no more than 60 per cent of GDP.

The behaviour of UK households in the 1970s and early 1980s fits what Robert Barro’s theory implied

The savings ratio drifted down from a peak of around 13 per cent in 1979 to around 4.5 per cent in 2000. Using figures taken from the Treasury Pocket Data Bank this was a period when government deficits fell from around 5.5 per cent of GDP to broad balance by the late 1990s and the stock of public debt fell from around 47 to 37 per cent of GDP. While the ratio of General Government Expenditure to GDP fell from 45 per cent under 38 per cent of GDP. Between 1979 and 2000 the aggregate tax burden was stable at around 35 per cent of GDP. Although that broad statistical gloss conceals a sharp rise in the tax burden in the early 1980s when total tax receipts, including revenue from oil reached 40 per cent of GDP in 1982-83, With receipts from non-oil GDP reaching 38.75 per cent in 1983-84. It is reasonable to infer from this that UK households adjusted their savings to higher inflation and higher budget deficits in the 1970s and 1980s; and as government deficits were turned into debt repayments and as the stock of public debt fell as a ratio of national income households saved less. In the 1970s and 1980 households had offset the behaviour of the public sector.

If Neo-Ricardian Equivalence may be plausible in previous British experience it is not clear that it tallies with either the behaviour of American households in the 1970s or the 1980s. James Poterba and Lawrence Summers in an article Finite lifetimes and the effects of budget deficits on national saving published in the Journal of Monetary Economics in 1987 showed that between 1981 and 1987, during the President Reagan deficits, as public borrowing rose, private saving fell and private consumption rose .

The interesting question is whether today households are again offsetting the actions of the public sector by their savings behaviour?

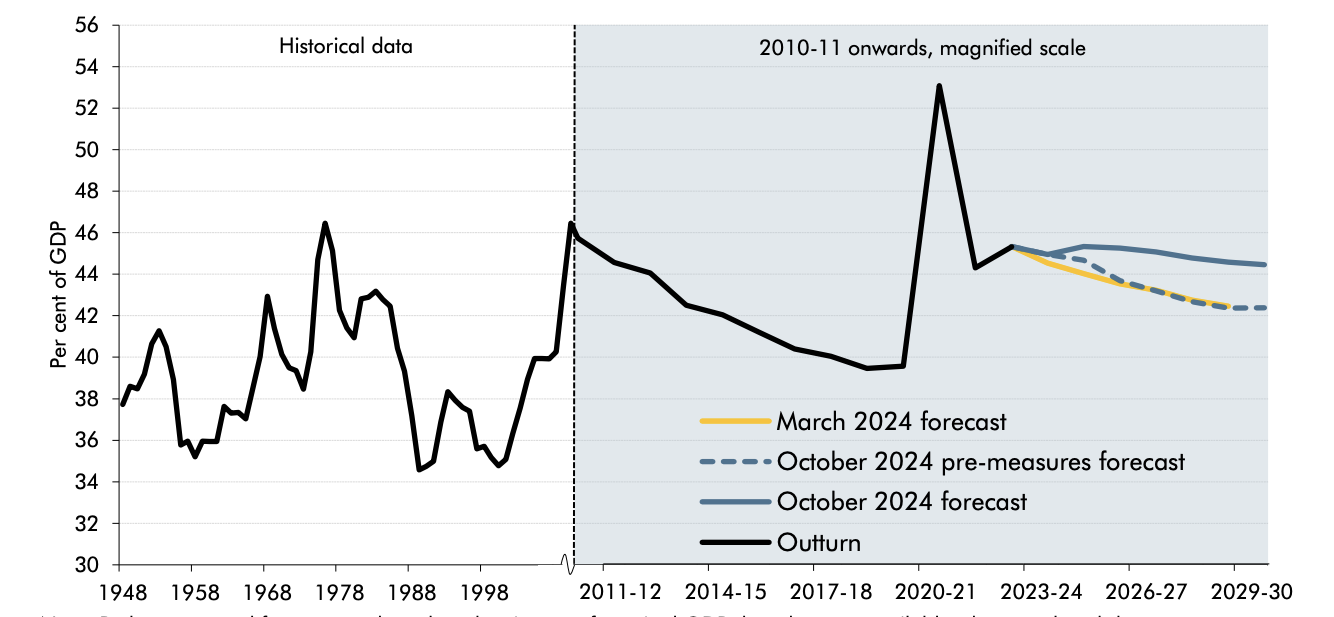

In the third decade of the 21st century it is possible that household behaviour may again be offsetting the chosen policy stance of the public sector. Since 2020 there has been a big increase in discretionary public spending. This has taken the ratio of Total Managed Expenditure from 39.8 per cent in 2019-20 to 45.3 per cent of GDP in 2025-26. This financial year public expenditure will be around five percentage points of national income higher than the position that the Office for Budget Responsibility projected in 2020. Public sector borrowing will be 3.6 per cent of GDP and is projected to be around 2.35 per cent over the next four years resulting in public sector debt rising from 96.9 per cent to 97 per cent of GDP.

Public Spending as share of GDP

Source OBR Economic and Fiscal Outlook October 2024

The decisions to increase spending, taxation and borrowing were taken between 2020 and March 2024; and further increases in the Budget in October 2024. Some of the decisions reflected the temporary costs of the covid public health emergency, others reflected deliberate discretionary changes to spending such as higher NHS spending. A decision to end the indexation of income tax allowances was made in the 2021 Budget. This raises tax revenue from aggravated fiscal drag. It is a return to bracket creep income tax regime the UK had before the introduction of indexation through the Rooker-Wise Amendment to the 1977 finance bill. The OBR in successive revenue forecasts estimates it will increase taxes by £38 billion.

There is a sufficiently animated contemporary British debate about tax increases that would stimulate most taxpayers out of a myopic ignorance about the future direction of the tax burden

Private households may well be responding to a broader awareness of a future rising tax burden than simply extrapolating from expected higher future borrowing. They may for example be forming a view about a higher ratio of public spending within national income. Not least because while fiscal rules may constrain deficits and debt they place no constraint on public spending.

National Accounts Taxes as share of GDP

Source OBR Economic and Fiscal Outlook October 2024

As well as the rising income tax burden projected by the OBR the increased future taxation, spending and borrowing that it projects there is an economic Greek chorus in the UK that calls for and expects higher taxes. These are the National Institute for Economic and Social Affairs, the Institute for Fiscal Studies, the Resolution Foundation and a network of commentators that the Financial Times accommodates in its civilised pink columns. As well as priming households to expect higher taxes these commentators have shown themselves adapt suggesting new taxes and changes to taxes that would raise specific taxes that are both among the most salient or noticeable taxes for the public and taxes that the public dislike. Among the kites being flown are : a wealth tax; heavier inheritance taxation by taxing inter-vivos gifts before death, effectively recreating the Capital Transfer Tax -CTT- of the 1970s; a mansion tax; and a reconstruction of the Council Tax to create a property tax analogous to the old rating system that the Layfield Inquiry was set up to examine because it was so unpopular. The suggested direction of travel is an overhaul in property taxation that would raise more revenue. This will be difficult, given that the UK raises twice the amount of tax revenue from property taxation than the OECD average. In this context a change in the savings behaviour of households could be taking place. A pattern of household behaviour where a higher savings ratio is exhibited, as it was in the 1970s and 1980s, could be being replicated in the contemporary economy.

Warwick Lightfoot

26 August 2025

Warwick Lightfoot is an economist and was Special Adviser to the Chancellor of the Exchequer between 1989 and 1992

Very interesting piece of analysis. Thank you, Warwick, for this.